| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Predatory Drones, Armored Vehicles & Warrior SWAT Team Cops, Battlefield Tactics, Jail Without Trial… on American Soil Against Americans!

“Post-Constitutional America” would be absolutely unrecognizable to an American from the sixties, seventies or even eighties.

Certainly not the men who, On July 30, 1778, created the first whistleblower protection law, stating “that it is the duty of all persons in the service of the United States to give the earliest information to Congress or other proper authority of any misconduct, frauds, or misdemeanors committed by any officers or persons in the service of these states.”

“.jpg) Two hundred thirty-five years later, on July 30, 2013, Bradley Manning was found guilty on 20 of the 22 charges for which he was prosecuted, specifically for “espionage” and for videos of war atrocities he released, but not for “aiding the enemy.”

Two hundred thirty-five years later, on July 30, 2013, Bradley Manning was found guilty on 20 of the 22 charges for which he was prosecuted, specifically for “espionage” and for videos of war atrocities he released, but not for “aiding the enemy.”

Days after the verdict, with sentencing hearings in which Manning could receive 136 years of prison time ongoing, the pundits have had their say. The problem is that they missed the most chilling aspect of the Manning case: the way it ushered us, almost unnoticed, intopost-Constitutional America.

The Weapons of War Come Home

Even before the Manning trial began, the emerging look of that new America was coming into view. In recent years, weapons, tactics, and techniques developed in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as in the war on terror have begun arriving in “the homeland.”

Consider, for instance, the rise of the warrior cop, of increasingly up-armored police departments across the country often filled with former military personnel encouraged to use the sort of rough tactics they once wielded in combat zones. Supporting them are the kinds of weaponry that once would have been inconceivable in police departments, including armored vehicles, typically bought with Department of Homeland Security grants. Recently, the director of the FBI informed a Senate committee that the Bureau was deploying its first drones over the United States. Meanwhile, Customs and Border Protection, part of the Department of Homeland Security and already flying an expanding fleet of Predator drones, the very ones used in America’s war zones, is eager to arm them with “non-lethal” weaponry to “immobilize targets of interest.”

Above all, surveillance technology has been coming home from our distant war zones. The National Security Agency (NSA), for instance, pioneered the use of cell phones to track potential enemy movements in Iraq and Afghanistan. The NSA did this in one of several ways. With the aim of remotely turning on cell phones as audio monitoring or GPS devices, rogue signals could be sent out through an existing network, or NSA software could be implanted on phones disguised as downloads of porn or games.

Above all, surveillance technology has been coming home from our distant war zones. The National Security Agency (NSA), for instance, pioneered the use of cell phones to track potential enemy movements in Iraq and Afghanistan. The NSA did this in one of several ways. With the aim of remotely turning on cell phones as audio monitoring or GPS devices, rogue signals could be sent out through an existing network, or NSA software could be implanted on phones disguised as downloads of porn or games.

Using fake cell phone towers that actually intercept phone signals en route to real towers, the U.S. could harvest hardware information in Iraq and Afghanistan that would forever label a phone and allow the NSA to always uniquely identify it, even if the SIM card was changed. The fake cell towers also allowed the NSA to gather precise location data for the phone, vacuum up metadata, and monitor what was being said.

At one point, more than 100 NSA teams had been scouring Iraq for snippets of electronic data that might be useful to military planners. The agency’s director, General Keith Alexander, changed that: he devised a strategy called Real Time Regional Gateway to grab every Iraqi text, phone call, email, and social media interaction. “Rather than look for a single needle in the haystack, his approach was, ‘Let’s collect the whole haystack,’ ” said one former senior U.S. intelligence official. “Collect it all, tag it, store it, and whatever it is you want, you go searching for it.”

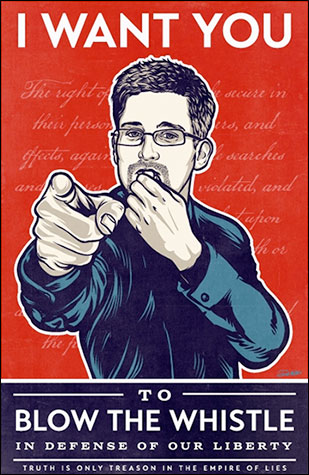

Sound familiar, Mr. Snowden?

Welcome Home, Soldier (Part I)

Thanks to Edward Snowden, we now know that the “collect it all” technique employed by the NSA in Iraq would soon enough be used to collect American metadata and other electronically available information, including credit card transactions, air ticket purchases, and financial records. At the vast new $2 billion data center it is building in Bluffdale, Utah, and at other locations, the NSA is following its Iraq script of saving everything, so that once an American became a target, his or her whole history can be combed through. Such searches do not require approval by a court, or even an NSA supervisor. As it happened, however, the job was easier to accomplish in the U.S. than in Iraq, as internet companies and telephone service providers are required by secret law to hand over the required data, neatly formatted, with no messy spying required.