| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Chet Raymo, “A Wildly Seething Power”

Thursday, January 10, 2013 20:20

% of readers think this story is Fact. Add your two cents.

“A Wildly Seething Power”

by Chet Raymo

by Chet Raymo

“I read Kierkegaard’s “Fear and Trembling” at about the same age as Kierkegaard was when he wrote it- thirty. The young philosopher was wrestling with his demons, including the death of his father, a sternly religious man who demanded absolute obedience from his son. He had jilted the woman he loved, a self-inflicted wound that perhaps not even he understood. He was torn, in my opinion, between the demands of faith and reason. Like many before him, he turned to the story of Abraham and Isaac as a way of understanding his own endangered faith.

The book begins with four retellings of the biblical story, each slightly different. In yesterday’s post, I added my own naturalistic retelling, suggesting what can go terribly wrong when one mistakes the voice in the head for the voice of God. Abraham’s dilemma is this: He believes the sacrifice of his son is required by God. What then is more important: Obedience to God or loyalty to his only son by Sarah? Heaven or earth? The unseen or the seen? What is it that gives meaning to a life?

Kierkegaard opts for faith- a leap of faith in the face of doubt. He writes: “If there were no eternal consciousness in a man, if at the foundation of all there lay only a wildly seething power which writhing with obscure passions produced everything that is great and everything that is insignificant, if a bottomless void never satiated lay hidden beneath all- what then would life be but despair? If such were the case, if there were no sacred bond which united mankind, if one generation arose after another like the leafage in the forest, if one generation replaced the other like the song of birds in the forest, if the human race passed through the world as the ship goes through the sea, like the wind through the desert, a thoughtless and fruitless activity, if an eternal oblivion were always lurking hungrily for its prey and there was no power strong enough to wrest it from its maw- how empty then and comfortless life would be.”

This is what Abraham wrestled with in the empty hours before dawn. This is the fear that drove him to choose heaven over earth, the unseen over the seen. This is the dread of a mindless oblivion that causes so many to choose faith over reason, righteous action over doubt.

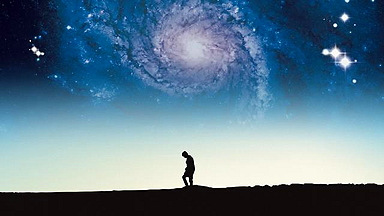

No less than the traditional theist, the scientific agnostic needs to believe that we are not poised above a bottomless void. We know – in our tentative and uncertain way – that our consciousness is ephemeral. And, yes, we know that one generation replaces another like the leaves of the forest. But we exalt in the leaves of the forest, and the song of the birds, and the wind in the desert. We stand in awe of the “wildly seething power which writhing with obscure passions produced everything that is great and everything that is insignificant,” and we struggle to understand that power through reason and observation, and in doing so we have come to know of the whirling galaxies, the stars that forge elements, the helices that spin out proteins in every one of the trillions of cells in our bodies. And in the darkest hours of the night, if we are lucky, we look across to Sarah sleeping beside us, and to Isaac lost in his young man’s dreams, and we understand that love and loyalty are blessings that well up out of the void in mysterious ways. We feel no need to make that terrible journey to Mount Moriah when every jot and tittle of creation, here and now, is filled- with sanctifying grace.”

- http://blog.sciencemusings.com/

2013-01-10 20:15:23

Source: http://coyoteprime-runningcauseicantfly.blogspot.com/2013/01/chet-raymo-wildly-seething-power.html

Source: