| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

Who Did Kill Rasputin?

Before the First World War the Russian royal family, the Romanovs, were heavily involved in occult activities. In the years between 1900 and 1905, the French occultist Dr. Gerard Encausse (Papus) made several visits to Russia for undisclosed reasons. In fact, he had been personally invited to the country by Tsar Nicholas II and was holding magical séances at the royal palace in St Petersburg for the tsar and his German-born wife, the Tsarina Alexandra. Both were interested in Spiritualism and the occult.

Dr. Encausse was a member of a French magical society called the Kabbalistic Order of the Rosy Cross (CORC). This was founded in France in 1888, the same year as the famous Order of the Golden Dawn in England. Dr. Encausse claimed to have been initiated into a Golden Dawn lodge in Paris run by Samuel Liddell Macgregor Mathers and his wife Moina. The Marquis Stanilas de Guaita and Josephin Peladan, two prominent French occultists, had created the CORC. Peladan had been born into an eccentric and fanatical Roman Catholic family who were supporters of the restoration of the French monarchy. His brother, Adrien, practised as a homeopathic doctor and had many wealthy and titled patients. He claimed to have been initiated in 1858 into a secret Rosicrucian order in Toulouse which had survived since the Middle Ages.

At the magical rituals held at the royal palace, Dr. Encausse attempted to conjure up the tsar’s dead father, Alexander III, who was also interested in Spiritualism. In fact, Alexander had invited the English medium D.D. Home to Russia to hold séances attended by aristocrats and members of the royal court.

In the early 1900s Russia was on the brink of revolution. There were riots in the streets, strikes, and rumours of mutiny in the armed forces. Against this turbulent background of civil disorder, the weak Tsar Nicholas II sought advice from the ‘Other Side’ on how to handle the situation. The message that came back from the spirits advised the tsar to resist the subversive and revolutionary forces threatening his throne, or he would lose control of Russia and topple from power. If the tsar did not take immediate action to deal with the deteriorating situation, then his authority and rule would be seriously undermined.

Despite this warning, Nicholas refused to act decisively and with the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the situation spiralled out of control as the spirits had predicted. This led to Nicholas losing his throne and eventually his life at the hands of Bolshevik revolutionaries. The vengeful Bolsheviks massacred his family and seized power from the democratic government set up after the tsar abdicated.

After his last visit to St Petersburg in 1905, Dr. Encausse stayed in contact with the tsar, and the occultist and the monarch exchanged letters at regular intervals. In this correspondence, they discussed various esoteric matters of mutual interest. However, Dr. Encausse confided to his fellow occultists that in his opinion Nicholas was a weak and easily influenced person who relied too much on his spiritual sources. The French magician believed that the tsar should instead listen more to his ministers and take their advice on the day-to-day running of the country.

The ‘Mad Monk’

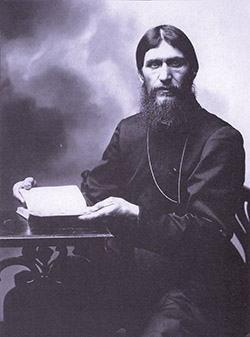

The French occultist became particularly worried about how the tsar and tsarina had fallen under what he regarded as the malefic influence of a charismatic wandering ‘holy man’ called Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin. Rumoured to have been involved with the unorthodox religious sect known as the Khlysty or ‘People of God’, Rasputin managed to be invited to the royal court. As a result, he became the spiritual advisor, friend and confidante of the Tsarina Alexandra and also forged relationships with other Russian aristocrats.

The Khlysty were a neo-Gnostic sect condemned by the Russian Orthodox Church because of their practices of flagellation and sexual indulgence to make contact with God and achieve spiritual enlightenment. At this time there were many quasi-religious sects in Russia and numerous wandering holy men and healers such as Rasputin.

How much the tsarina knew of Rasputin’s background is not known, but she must have been aware he was using his personal charm and hypnotic powers to seduce many of her female courtiers. Although there is no evidence they had a sexual affair, Alexandra seems to have been infatuated with the unkempt ‘holy man’. She was in awe of his magical powers after he used his healing abilities to save the life of her haemophiliac son, the heir to the imperial throne. From then on, she would not allow anyone to say a bad word against him.

Despite his wild physical appearance, Rasputin exerted a strange power over women, especially wealthy ones. It was said this was due to his ability to withhold orgasm for long periods. One aristocratic lady said the experience of making love with Rasputin was so pleasurable that she actually fainted during it. Such comments have led some writers to suggest the ‘Mad Monk’, as his enemies dubbed him, was a skilled adept in Tantric techniques from Eastern occultism and a practitioner of sex magic.

Many friends of the Romanov royal family and members of the Russian government warned the tsar that Rasputin’s influence over his wife was sinister and evil. Dr. Encausse also wrote to Nicholas and warned him that in Kabbalistic terms the holy man was an unholy vessel like Pandora’s famous box of misfortune. As such, he contained all the “vices, crimes and filth of the common Russian people.” Prophetically, the French occultist said if the vessel was ever broken (i.e. Rasputin was killed) all its “dreadful contents will spill across Russia” destroying everything they touch.

Prelude to The Great War

In the 1900s it was widely expected there would soon be a war involving the major European powers. It was alleged that at a secret conference in Brussels, attended by leading Freemasons and members of secret societies as early as 1905, a plot had been hatched to bring down the Romanovs along with the other crowned heads of Europe. As the Great War approached, it was believed Rasputin was their secret weapon in achieving this aim.

The First World War broke out in August 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife the Archduchess Sophia of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When they were killed in Sarajevo, Bosnia by members of a secret society of Serbian nationalists known as the Order of the Black Hand, Rasputin warned the tsar not to let Russia get involved in a war with Germany. The monk predicted that if the Russian armed forces joined with those of Britain and France against Germany and their Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian allies, the country would suffer “a terrible defeat.” In the violent civil disorder to follow, the monarchy would fall from power. For once, the tsar ignored the advice of his ‘spiritual sources’ and committed the imperial Russian army and navy to the allied cause against Germany.

Following the assassinations in Sarajevo, Tsarina Alexandra sent Rasputin several urgent telegrams asking for his advice about the international situation. Rasputin replied that on no account should Mother Russia get involved if, as was widely expected, war broke out among the major European powers. If she did, “It will be the finish of all things.” It is presumed Rasputin was not aware Russian secret agents had been implicated in the assassination plot. Allegedly, the Russian military attaché in Belgrade had paid 8,000 roubles to the leaders of the Order of the Black Hand. The attaché had also told them that Tsar Nicholas II would support the cause of Serbian nationalism if war broke out between Russia and the Austro-Hungarian-German alliance.

It was also rumoured that in early 1914 representatives of the Black Hand had secretly met with members of the politically subversive French Masonic lodge of the Grand Orient at the Hotel St Jerome in Toulouse, France. At this meeting the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph and Archduke Ferdinand had been discussed. The plot was organised by the Black Hand with renegade elements of French Masonry and allegedly had the tacit support of the Russian tsar. The idea was to create the right conditions for a war between the European monarchies leading to their destruction, although why Nicholas II would support the anti-royalist plan remains unclear as he had all to lose from it.

Following the murder of Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Kaiser Wilhelm told the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin that military force had to be used to neutralise Serbian nationalism and he offered his country’s support in any action the empire decided to take. The Kaiser quoted intelligence reports that suggested Russia would not intervene. On 28 July 1914, four weeks after the assassinations, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on Serbia. In response to this, Tsar Nicholas ordered the Russian army to mobilise. The Kaiser warned the tsar that unless his forces stood down he would mobilise German troops. Five days later, when this ultimatum had been ignored, Germany declared war on Russia and the First World War began.

When war was declared, Rasputin said if he had not been ill he would have travelled to St Petersburg to see the tsar personally. If this had happened, he boasted, Russia would never have entered the war and he would have single-handedly changed the course of world history. The pro-war elements claimed Rasputin was a pacifist and a pro-German traitor. It was even said the holy man was a secret agent working for the German intelligence service. The Germans had allegedly planted him in the royal palace to give the tsar and tsarina false advice and counsel.

As the war dragged on, the rising casualties at the front and food shortages at home led to strikes and riots, and open hostility to the Romanovs surfaced among the population. This unrest was aided and abetted by the subversive activities of left-wing socialist and revolutionary agitators who wanted to replace the existing regime with a worker’s republic. Rasputin meanwhile had received a psychic premonition of impending doom and believed his life was under threat. In 1916 he wrote to the tsar spelling out the consequences to Russia and the Romanov dynasty if he was killed. He said should he be murdered by common assassins who were Russian peasants, whom he described as his “brothers,” the royal family would have nothing to fear. If, however, his killers were aristocrats, then “brother will kill brother” and no nobles would be left in the country.

Several political factions in Russia had previously attempted to stop Rasputin’s influence on the royal family by violent means. In 1913 a conspiracy was revealed to kidnap the mystic monk, castrate him because of his sexual activities, and then kill him. Rasputin, however, was tipped off about the plot and managed to evade capture.

A year later, on 19 July, a prostitute attacked Rasputin while he was holidaying at the Black Sea resort of Yalta, later to be the meeting place of the Allied wartime leaders towards the end of the Second World War. The prostitute stabbed Rasputin in the stomach, but despite losing a considerable amount of blood, he managed to survive the attack. When questioned by police, the woman said she had tried to murder the so-called ‘holy man’ because he was a heretic and ‘fornicator’ who had seduced a nun. She was diagnosed as unfit to stand trial due to insanity and was committed to a mental hospital. This appears to be an official cover-up.

Significantly perhaps, the assassination attempt on Rasputin occurred only weeks after the murder in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife by members of the Black Hand secret society.

Enter the SIS

Rasputin’s prediction of his own death came eerily true in December 1916, when a group of right-wing aristocrats conspired with the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6 or Military Intelligence Department Six) to kill him. The SIS was a branch of the Foreign Office set up in 1909. According to Michael Smith’s book Six: A History of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service: Part 1: Murder and Mayhem 1909-1939, at the beginning of the First World War the head of SIS in London, known by the code letter ‘C’, made overtures to the Russian intelligence service. This was because of serious British concerns about the commitment of Tsar Nicholas II to the war effort. In September 1914, ‘C’ was granted permission by the Foreign Office in London and the Russian government to send several military officers to set up a SIS bureau in Petrograd, the new name for St Petersburg. Its name had been changed because the original sounded too German.

One of the SIS officers, Lieutenant Stephen Alley, was a fluent Russian speaker who had been born in a village near Moscow. Before the war he worked in Russia for the Maikop & General Petroleum Trust, an American oil company owned by the future US president Herbert Hoover. The company was building a new oil pipeline across southern Russia to a port on the Black Sea. When war broke out, Lt Alley left the company and joined the British Army. He was then recruited by military intelligence, joining the SIS. Because of his Russian background, Lt Alley was sent to Petrograd posing as a military attaché to the British Embassy.

The British intelligence officer soon discovered there were members of the Russian government, especially in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who were worried about the way the war was going. Some went so far as to support a separate peace treaty with Germany. Apparently there had been several clandestine meetings between officials of the two countries at the Russian and German embassies in Rome. It was said the Grand Duke of Hesse in Germany had even been in personal touch with the German-born tsarina. He had urged her to use her influence with her husband and members of the Russian government to seek a peace agreement.

In November 1915, Lt Alley was in charge of what the SIS Russian bureau termed ‘background intelligence operations’. Two other officers, who had been recently sent out from SIS’s London headquarters, assisted him. One of them, Lt Oswald Rayner, was originally given the task of secretly opening and examining telegrams and letters. The SIS was particularly interested in the activities of neutral Swedish shipping companies believed to be supplying goods to Germany in defiance of the Royal Navy’s blockade.

Before joining the Secret Service, Rayner had worked in Finland, then a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire. He taught English and befriended a wealthy local couple who funded his further education at Oxford University, where he studied modern languages. At Oxford, he became friendly with Prince Feliks (Felix) Yusupov, a member of one of the wealthiest and most influential aristocratic families in Russia. Rayner then worked as a correspondent for The Times newspaper in London and later joined the civil service where he became a friend of the future wartime prime minister, David Lloyd George. When war broke out in 1914, Rayner joined the British Army. He was commissioned as an officer and assigned to ‘special duties’ with the SIS. Like Lt Alley, his fluency in Russian had him sent to Petrograd to join the British Secret Service unit operating in the city.

With persistent rumours circulating that the Russian government was keen to make peace with Germany, the SIS began to focus on the specific stories about Grigory Rasputin, his alleged involvement in a pro-German anti-war peace movement and his peculiar influence over the tsarina. Their intelligence suggested the holy man was either the leader or at the very least a leading mover in a so-called ‘peace party’ made up of politically prominent Russians.

As a result, several right-wing pro-war elements within the Russian aristocracy were counter-plotting to remove Rasputin permanently so he could not influence the tsar and tsarina with his views. One of these conspirators, a member of the Duma or Russian parliament, Vladimir Purishkevich, approached a SIS officer offering information on the plot. He told the officer a plan had been drawn up to “liquidate Rasputin.” At the time, the officer was unaware that three of his SIS colleagues, Alley, Rayner and an ex-Indian Army officer Captain John Dymoke Scale, were in fact closely involved in the plot to kill Rasputin.

Lt Alley and Capt Scale had become suspicious of the tsarina’s close relationship with her spiritual advisor. Knowledge of Rasputin’s pro-German sentiments was common knowledge by 1916. Even The Times accused him of being a Germanophile whose influence at the Russian royal court was described as both “potent” and “baleful.” Capt Scale described Rasputin as a “drunken debaucher” who was adversely influencing Russian government policy and “clogging the war machine.” It was becoming evident the Mad Monk had to be neutralised, and this could only be achieved by his death.

The Plot to Kill Rasputin

The key figure in any British Secret Service involvement in a plot to terminate Rasputin with ‘extreme prejudice’ would be Lt Oswald Rayner. This was because of his long friendship with Prince Yusupov who was the leader of the conspirators. The prince invited the holy man to a ‘party’ at his family’s palace on the banks of the River Neva in Petrograd. Yusupov persuaded his wife, Princess Irina, the niece of Tsar Nicholas, to lure the monk to the party, although she was not actually going to be present. It was a typical British Secret Service ‘honey-trap’ operation that has been carried out many times since. Also present at the party was a prominent aristocrat, the Grand Duke Dimitry Pavlovich, the tsar’s second cousin; an army officer, Lieutenant Syukhotin, who was a close friend of the prince; Vladimir Purishkevich; an army medic Dr. Stanilaus de Lazoret – and the SIS officer Lt Oswald Rayner.

The usual version of events is that Rasputin was first given some small chocolate cakes and wine laced with cyanide. When these had no apparent effect, he was shot in the chest at close range with a revolver. The holy man apparently survived this, attacked his would-be killers and managed to escape from the house. The assassins pursued him and he was shot three more times. His body was then bundled into a car and driven to the Petrovsky Bridge over the River Neva, where it was thrown into the icy waters. Despite the poison and several gunshot wounds, Rasputin was still alive, if barely, when he was tossed into the river and drowned.

In reality, when Rasputin arrived at the prince’s home he was given copious amounts of alcohol until he was drunk. He was then tortured, beaten with a leather cosh on the testicles. There may have been a sexual element to this, but the aim was to get Rasputin to confess to his anti-war activities and name the other pro-German conspirators involved. Finally, he was shot several times using at least three different weapons. It is alleged that Rayner used his standard Secret Service issue Webley revolver to fire the last shot that finally finished off Rasputin. His body was then disposed through a hole in the ice of the frozen river.

It is not clear if the senior officer running the SIS Russian bureau in Petrograd was fully aware of the involvement of Rayner and the other British officers in Rasputin’s murder. He expressed total surprise at the news when relaying it to ‘C’ in London. There is indication the three SIS officers had not received official sanction for the operation. They acted without London’s approval because they feared that the plan for a Russian peace treaty with Germany was well advanced. In fact, under torture Rasputin had even named a date in January 1917 when it would be signed.

Two of the three SIS officers seemed to have been quickly posted elsewhere. Capt Scale was not even in Russia when the operation was carried out. He had already been sent to Romania to assist in a SIS operation to prevent the invading German army from capturing and using the oilfields and grain stores in the country by sabotaging them. He was later to return to Petrograd where rumours were still rife that the British Secret Service had somehow been involved in Rasputin’s death.

Lt Oswald Rayner was transferred to SIS’s Stockholm office, but Lt Alley stayed in Russia and took over as head of the bureau. He eventually was given the role of liaison officer with the new provisional government and had the task of persuading them to keep the faith by pursuing the war with Germany. He was later sacked from SIS for allegedly refusing to carry out an order to assassinate one of the Bolshevik revolutionary leaders – Josef Stalin. The real reason was said to be that ‘C’ in London wanted to get rid of Lt Alley. It is possible this was because of the lieutenant’s alleged involvement in the plot to torture and murder Rasputin.

The reaction to and consequences of the death of the Mad Monk were immediate, confirming the holy man’s own predictions about the event at the hands of the aristocracy. The Russian peasantry held him in great regard and reverence. When the news of his violent death spread, he was treated like a religious martyr and the finger of suspicion was pointed at the royal palace. Following the murder, rumours began to circulate of a right-wing coup by army officers to oust Tsar Nicholas II because he was a weak leader who was losing the war for Russia. The secret police investigated these stories, but in fact the real threat to the tsar’s continued rule and precarious position came from extreme left-wingers and, ironically, the supporters of a liberal democratic form of government.

Fall of the Monarchy

In March (or February by the Old Calendar still used in Russia) 1917, food riots broke out in Petrograd and other major Russian cities. Troops sent to put them down instead sided with the hungry demonstrators and joined them in their protest. As law and order broke down, a new liberal democratic provisional government was appointed to run the country. Faced with widespread and mounting criticism and a violent reaction to his policies, Nicholas decided the best thing for the country was to abdicate in favour of his younger brother, Grand Duke Michael. Unfortunately, the new tsar did not have the support or confidence of the peasants and, more importantly, the police and armed forces. In turn, Michael was forced to abdicate and he passed his executive powers to the provisional government. This move was widely applauded in Western capitals, as it was mistakenly believed that Russia was entering a new era of democracy replacing the autocratic rule of the tsars.

Unfortunately, divided by internal disputes and trying to fight an increasingly unpopular war, the provisional government ruled for only eight months until November (or October) 1917. During this short period of democratic rule, it did manage to promote freedom of speech, religious worship and assembly and ended the censorship of the press. This freedom was short lived as in July 1917 a group of soldiers, sailors and Bolsheviks attempted to seize Petrograd. They were only prevented from doing so by the intervention of regular army units who were still loyal to the provisional government.

Kaiser Wilhelm, himself interested in Spiritualism with an extensive private library of occult books, also decided to interfere in Russia’s internal affairs. He allowed the Bolshevik revolutionary leader Vladimir Illyich Lenin to return to Russia from Switzerland via Germany with his followers in a sealed train. Lenin promised Kaiser Wilhelm that if he managed to seize power by overthrowing the provisional government the war would be ended. On his arrival in Russia, Lenin was greeted by jubilant crowds and finally on 7 November (October) 1917, the Bolsheviks seized power. Troops from the garrison in Petrograd mutinied and, assisted by sailors and an armed workers’ militia called the Red Guard, they stormed the Winter Palace.

Russia’s New Government

The Bolshevik revolution was not bloodless by any means as in 1918 fighting broke out between the new Soviet government and the so-called ‘White Russians’ led by aristocrats still loyal to the monarchy. The Allies intervened and American, British, French and Italian troops landed on Russian soil. Their mission was to help the White Russians in the civil war and to seize materials stored in the ports of Archangel and Murmansk so they would not fall into the hands of the Germans. From October 1919 until January 1920, Allied forces blockaded the Russian coast and supplied the White Russians with military equipment.

Despite their intervention, the Allies failed to prevent the ultimate defeat of the White Russian forces and the eventual establishment of the Soviet Union. In 1918, Tsar Nicholas, his wife and their children were brutally murdered by the Bolsheviks in the cellar of a house in Ekaterinburg, where they had been held captive. Rasputin’s prediction had come true. Nicholas had tried to seek asylum in Britain, but his cousin King George V, persuaded by his government, refused him and his family refuge. The king never fully recovered from the guilt he felt over the matter. Ironically, one of the first acts of the new Bolshevik regime was to ban all religious sects, occult groups and secret societies that had flourished in imperial Russia under the rule of the Romanov dynasty.

If you appreciate this article, please consider a digital subscription to New Dawn.

.

MICHAEL HOWARD is an Anglo-English writer, historical researcher, and magazine editor and publisher. Since 1976, he has been the editor of The Cauldron witchcraft magazine www.the-cauldron.org.uk. He has been studying the links between the occult and politics since he was a teenager and is the author of Secret Societies: Their Influence and Power from Antiquity to the Present Day (Destiny Books, 2008).

The above article appeared in New Dawn Special Issue Vol 8 No 3

Read this article with its illustrations and sidebars by downloading

your copy of New Dawn Special Issue Vol 8 No 3 (PDF version) for only US$4.95

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.

Source: http://www.newdawnmagazine.com/articles/who-did-kill-rasputin