| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Noisy Surroundings Take Toll On Short-Term Memory

Noisy surroundings take toll on short-term memory. Speech content and bad acoustics draw on same limited brain resources.

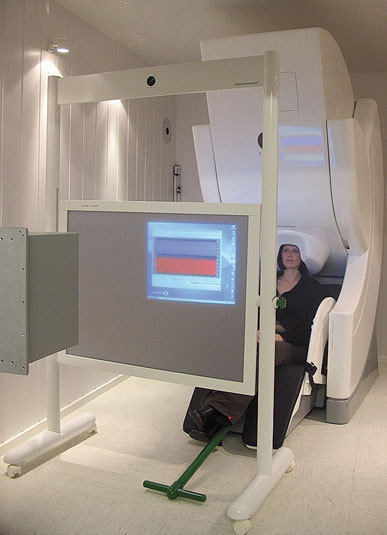

By recording fluctuations in magnetic currents which occur when nerve cells in the brain communicate with each other, magnetencephalography (MEG) can record the brain’s reaction to a stimulus with millisecond precision.

© MPI CBS

Whether we are engaged in small talk or trying to memorise a telephone number – it is our short-term memory that ensures we don’t lose track. But what if the very same memory gets additionally taxed because the words to be remembered are hard to understand? This is suggested by a new study conducted by Jonas Obleser and his team at the Max Planck Research Group “Auditory Cognition”

In the experiment, listeners were asked to memorise a few digits they heard (e.g., “2…5…9…3”) for just over a second. This is a very easy task, and when asked whether they remembered hearing a certain digit, listeners answered correctly 90 percent of the time. During this process, Obleser and his colleagues were using magnetoencephalography to measure so-called “alpha waves” in the brain. “The brain tends to time its activity in rhythmic waves with the alpha rhythm consisting of 8 to 12 activity waves per second”, Obleser explains. “The reason we were interested in this particular rhythm is that the strength of the alpha waves has been shown to indicate how much information you are currently storing in your short-term memory, with more vigorous alpha waves signalling a busier time.”

As expected, alpha waves were stronger when listeners had more digits to memorise. But surprisingly, the strength of the alpha waves also depended on the acoustic format of the speech signal, which the scientists varied from clear to heavily degraded. The harder the digits were to understand, the stronger the alpha waves became. Speech content (e.g., a phone number you would like to remember) and speech acoustics (such as the noisy party at which you overheard that phone number) thus draw on a shared brain resource.

While participants kept the numbers they had heard in mind, alpha wave increased, peaking, when bad acoustics were combined with longer strings of numbers.

© MPI CBS

In our everyday lives our short term memory has a natural limit, which may be reached faster in noisy surroundings. These findings may be particularly relevant to populations who are constantly receiving such adverse input: People with hearing damage, or – most drastically – people who have restored but very fragmented hearing through an artificial inner ear, the so-called cochlear implant.

Further studies could examine in further detail how chronic sensory degradations affect the executive functions of the brain.

Contacts and sources:

Dr. Jonas Obleser

Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig