| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

“Samuel and Daniel, Though Young, Judged the Elders”: Traditionalism as a Youth Movement

“And on no occasion whatsoever should age distinguish the brethren and decide their order [in the monastery]; for Samuel and Daniel, though young, judged the elders” (ch. 63).[1]

“As often as any important business has to be done in the monastery, let the abbot call together the whole community and himself set forth the matter. And, having heard the advice of the brethren, let him take counsel with himself and then do what he shall judge to be most expedient. Now the reason why we have said that all should be called to council is that God often reveals what is better to the younger” (ch. 3).[2]

The saint’s advice seems all the more relevant in today’s Church, when it is clearly the young who are rediscovering Catholic Tradition in all its fullness, and who, at the same time, are bearing the full brunt of the resistance of their elders, who have been “sticks in the mud” when it comes to welcoming this stirring of the Holy Spirit. In this curious way, today’s older generations often seem like the Jews in the Gospels, who cannot receive the newness of Christ and his apostles (cf. Acts 7:51).

Of course, it need hardly be said that St. Benedict’s advice also applies perfectly to monasteries, convents, and other religious houses, where, let us be frank about it, revival or even bare survival is bound up with a recovery of traditional liturgy, in both the Divine Office and the Mass, and in the chant.[3] It is no longer a secret that the most flourishing communities are the ones that have unashamedly restored the way of life that a foolish generation threw away in the name of aggiornamento. A certain Benedictine monk told me that in the late 1960s, when his monastery switched over to a liturgy entirely in the vernacular, a member of the community actually put all of the copies of the Antiphonale Monasticum into a wheelbarrow, carted them outside, built a bonfire, and burned them. Another monk, horrified, gathered as many copies of the Graduale Romanum as possible and hid them so that they would be spared a similar fate. How many precious volumes, repositories of the wisdom and beauty of ages, were destroyed in this barbaric manner? “Vengeance is mine,” says the Lord (Deut 32:35; Rom 12:19); one can be certain that those who sinned against Catholic tradition have paid the last penny for it.

When I was being given a tour this past October of a famous Benedictine monastery near Krakow, the young monk who was my guide stated outright that the younger monks wish to have the tabernacle back in the center, wish to have Mass ad orientem, and wish to receive communion kneeling and on the tongue, while their elders are opposed to all of these things. It is not merely “generational dynamics,” as if we ought to expect the next generation to clamor for the opposite again. No. It is an awakening at last from the Rip van Winkle sleep of progressive liturgism — that weird coma between the ill-informed but thriving conservatism of the preconciliar age and the better-informed though struggling traditionalism of the postconciliar age.

We have heard and still hear a lot about the “charismatic movement,” but no one can explain how in the world it is supposed to fit in with the Catholic Faith as it has matured and blossomed in the miracle-rich lives of the saints, full of ascetical sobriety and mystical transcendence, which are perfectly mirrored in the liturgical and sacramental rites they knew and loved. Traditionalism is the real charismatic movement in the Church today, and it is high time that we stop thwarting the Spirit. Would that today’s shepherds and sheep would heed Gamaliel’s hard-nosed advice:

Ye men of Israel, take heed to yourselves what you intend to do, as touching these men. For before these days rose up Theodas, affirming himself to be somebody, to whom a number of men, about four hundred, joined themselves: who was slain; and all that believed him were scattered, and brought to nothing. After this man, rose up Judas of Galilee, in the days of the enrolling, and drew away the people after him: he also perished; and all, even as many as consented to him, were dispersed. And now, therefore, I say to you, refrain from these men, and let them alone; for if this council or this work be of men, it will come to nought; but if it be of God, you cannot overthrow it, lest perhaps you be found even to fight against God. (Act 5:35-39)

“If it be of God, you cannot overthrow it.” No member of the body of Christ, high or low, can fight against God and win. The traditionalist movement is here to stay and is growing. Its adherents truly believe that the Eucharistic liturgy is the font and apex of life, and act accordingly. Those who oppose this movement are not just setting themselves up for failure, but setting themselves up against the God who has inspired such a deep attachment to the means of sanctification He Himself bestowed on the Church. The sacred liturgy as well as the desire of the people to worship God through it are both of the Holy Spirit. As we know, the sin against the Holy Ghost is the only sin that can never be forgiven, in this world or in the world to come.

The stakes are high. Choose well. Choose with discretion and courage, as did Samuel and Daniel, who, “though young, judged the elders.”

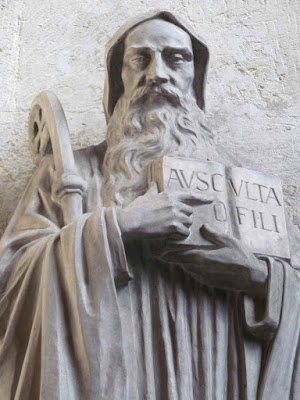

St. Benedict, Father of Western Monasticism, Co-Patron of Europe, whose feast we begin to celebrate at First Vespers this evening, pray for us.

NOTES

[1] Rule, ch. 63 (McCann ed.), p. 143

[2] Rule, ch. 3, p. 25.

[3] See Paul VI’s Sacrificium Laudis.

Source: http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2017/03/samuel-and-daniel-though-young-judged.html