| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

More NGDP Targeting Concerns: Gavyn Davies Edition

where he responds to Michael Woodford’s call for a NGDP level target.

Davies is always a good read, but this time he raises some concerns

about NGDP level targeting that are unwarranted. He claims that the

Fed may be uncomfortable with a NGDP level target because it might

unmoore inflation expectations, it might be seen as time-inconsistent

with the Fed’s long-run objectives, and finally it may be too late to

return NGDP to its pre-crisis trend. While understandable, the first

two concerns are without merit under NGDP level targeting. This

approach to monetary policy actually anchors long-run inflation

expectations and provides a credible way to commit. The last concern

has more merit, but even here it is not a clear-cut case. Let’s look at

each of these concerns in turn.

[T]here is one

obvious reason why the Fed might feel uncomfortable with some aspects of

the Woodford approach: it might unhinge inflation expectations from the

2 per cent anchor which has been in place for more than a decade, and

which was so costly to establish in the 1980s and 1990s… And greater uncertainty about the

future rate of inflation could damage the real economy.

to Cochrane, this concern assumes that the temporarily higher inflation

would be viewed as a discretionary, ad-hoc surge in inflation. But

that is not the case under a NGDP level target:

A level target anchors long-run

inflation expectations, but allows for temporary catch-up growth or

contraction in NGDP so that past misses in aggregate nominal expenditure

growth do not cause NGDP to permanently deviate from its targeted

path. Woodford notes that currently NGDP is anywhere from 10-15% below

its trend (and thus expected) growth path. Any increase in inflation

under this target, therefore, would not be some ad-hoc temporary

increase but part of a systematic approach that would return NGDP to its

trend.

The point is that these temporary

increases (or declines in the case of a boom) in inflation would be seen

as part of a systematic response of monetary policy that simply

returned nominal incomes to some stable growth path. And the expected

stable nominal income path would anchor long-run inflation expectations

as I noted in my reply to Cochrane:

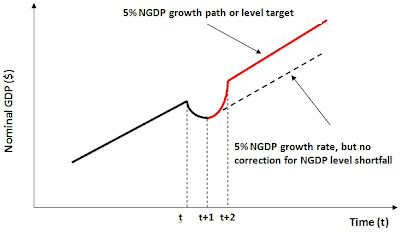

The black line has NGDP growing at a 5% annualized rate. Then, at time t a negative aggregate demand (AD) shock causes NGDP to contract through time t+1.

There is now an a NGDP shortfall. To make up for it, the Fed must

actually grow NGDP significantly faster than 5% to return aggregate

nominal spending to its targeted level. For example, if NGDP fell 6%

between t and t+1 it is now 11% under its trend. Next

period the Fed must make up for the 11% shortfall plus the regular 5%

growth for that period. In short, the Fed would need to grow NGDP about

16% between t+1 and t+2 to get back to trend. There

might be temporarily higher inflation as part of the rapid NGDP growth,

but over the long-run a NGDP level target would settle back at 5%

growth. Nominal and thus inflationary expectations would be firmly

anchored.

Woodford, himself, made this point in his paper:

[S]uch a commitment would accordingly require pursuit of nominal GDP

growth well

above the intended long-run trend rate for a few years in order to close

this gap. At

the same time, such a commitment would clearly bound the amount of

excess nominal income growth that would be allowed, at a level

consistent with the Fed’s announced long-runt target for inflation.

In

short, Woodford is saying a NGDP level target firmly would anchor

long-run inflation expectations and other nominal variables. So this

first concern is not an issue.

What about Gavyn Davies’ second concern? Here it is:

A

second reason for possible Fed concern is more institutional in nature,

concerning the long term credibility of the Fed. Professor Woodford’s

recommended target framework risks being seen as time inconsistent. The

optimal policy for the Fed today is not optimal for a future FOMC to

pursue, once the economy has recovered, and inflation is above 2 per

cent. The pressure on the future FOMC to renege would be enormous. The

markets know this today, so would the commitment to the NGDP framework

be credible in the first place?

under a NGDP level target any temporary easing (or tightening) in the

short-run is very time consistent, because it is returning nominal

income to the Fed’s long-run growth path target. That’s kind of the

point of level targeting, it coordinates short-run policy

moves with long-run policy objectives. Under a NGDP level target,

everyone understands the “catch-up” nominal income growth is temporary

and tied to an objective. The public would also understand that once

the target path was hit, nominal income growth would slow to trend.

They would come to expect it. In other words, there are no

inconsistencies between the short-run and long-run.

a NGDP level target would create so much credibility that the markets

would end up doing the heavy lifting. If the markets know the Fed will

do whatever is necessary (i.e. buy or sale as many assets as needed) to

return nominal income to its target growth path, than this expectation

causes the public to start adjusting spending and investment choices

today. For example, let’s say the Fed announced that QE3 was now aimed

at raising NGDP 10% to hit its pre-crisis trend and that it would start

buying every week enough securities to make sure that it happened. This

would be a huge slap to the face of the market and cause a major

rebalancing of portfolios. This rebalancing would create wealth

effects, improve balance sheets,and ultimately spur nominal spending.

The Fed would not have to purchase that many securities. Just the

threat of doing so would be sufficient.

a NGDP level target would create such credibility and thereby improve

management of expectations, this approach would also tend to

automatically reduce the occurrence of AD

shocks in the first place. Michael Woodford agrees:

A commitment not to let the target path shift down means that, to the

extent that the target path is undershot during the period of a binding

lower bound for the policy rate, this automatically justifies

anticipation of a (temporarily) more expansionary policy later, which

anticipation should reduce the incentives for price cuts and spending

cutbacks earlier, and so should tend to limit the degree of the

undershooting. Such a commitment also avoids some of the common

objections to the simple Krugman (1998) proposal that the central bank

target a higher rate of inflation when the zero lower bound constrains

policy.

Credibility is not an issue for well-implemented NGDP level target. Angst

Davies’ final concern is that the price level, one component of NGDP,

is already back to trend and that the trend path of potential real GDP

has declined since the crisis. Therefore, returning NGDP to trend would

ultimately result in an permanently higher price level path than

expected, since closing the real GDP gap would not suffice by itself to

close the NGDP gap. That is a reasonable concern that others have

brought up before. The problem with this concern is that it is based on

Davies’ estimation of a trend line. Others, like Tim Duy,

have fitted lines that put the price level currently below its trend.

Similarly, the decline in potential real GDP may prove to be temporary

once the economy starts roaring again, a point made by Mark Thoma. If

so, then the closing the real GDP gap may suffice for closing the NGDP

gap. Still, there is a lot of uncertainty over how much of the NGDP

gap can be closed. One simple solution suggested by Scott Sumner is to

set a slightly lower target growth path for NGDP than the pre-crisis

trend. This concern, therefore, should not be a game changer for

whether the Fed adopts an explicit NGDP level target.

then, Gavyn Davies concerns about implementing a NGDP level target are

unwarranted. If the Fed decided to follow an explicit NGDP level target

then inflation expectations should not become unanchored and

credibility should not be an issue. Now one might reply that the Fed

could never really commit to a NGDP level target in the first place.

That is a different argument and if true points to deeper problems at

the Fed that would affect the effectiveness of any targeting regime the

Fed adopted, not just a NGDP level target. This too, however, could be

addressed by Congress changing the Fed mandate to NGDP level targeting.

P.S. Scott Sumner makes the overall best case for NGDP level targeting here.

2012-10-05 23:03:55

Source: http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2012/10/more-ngdp-targeting-concerns-gavin.html

Source: