| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

The Trolley Problem

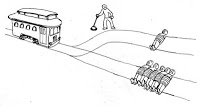

A trolley has lost its brakes, and is about to crash into 5 workers at the end of the track. You find that you just happen to be standing next to a side track that veers into a sand pit, potentially providing safety for the trolley’s five passengers. However, along this offshoot of track leading to the sandpit stands a man who is totally unaware of the trolley’s problem and the action you’re considering. There’s no time to warn him. So by pulling the lever and guiding the trolley to safety, you’ll save the five passengers but you’ll kill the man.

Most people pull the switch, killing the one man to save five. That wouldn’t be so interesting by itself, but then the problem is extended to a seemingly similar problem:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you – your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

Most people would not push the fat man. These grave dilemmas constitute the trolley problem, a moral paradox first posed by Phillipa Foot in her 1967 paper, “Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect.” I don’t really like any of the popular resolutions as to why people think it’s OK to kill the first guy but not the second.

I think a good resolution is that in the second case there is a significant probability that one does not save the 5 men, and instead merely kills the fat man. I’ve never pushed a fat man in front of a trolley, but I suspect most would simply run right over him and keep going. In the first case, if you killed the one man you definitely save the five men, it’s not possible to kill both the one man and the five men by switching tracks. In the other case the probability is clearly less than 1, perhaps only 0.1. That’s the difference. As a rule, acting on a theory and killing x people with certainty to perhaps save 5x people is morally wrong, mainly because these theories are often wrong, so all you do is kill x people (eg, a lot of evil is legitimized as breaking eggs to make an omelette, but then there’s no omelette). The move from certainty to mere ‘highly likely in my judgment’ is huge.

2012-12-17 00:24:47

Source: http://falkenblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/the-trolley-problem.html

Source: