| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

The Balance Sheet Recession That Never Happened: Australia

Monday, January 25, 2016 8:03

% of readers think this story is Fact. Add your two cents.

Probably the most common explanation for the Great Recession is the “balance-sheet” recession view. It says households took on took on too much debt during the boom years and were forced to deleverage once home prices began to tank. The resulting drop in aggregate spending from this deleveraging ushered in the Great Recession. The sharp contraction was therefore inevitable.

But is this right? Readers of this blog know that I am skeptical of this view. I think it is incomplete and misses a deeper, more important story. Before getting into it, let’s visit a place that according to the balance sheet view of recessions should have had a recession in 2008 but did not.

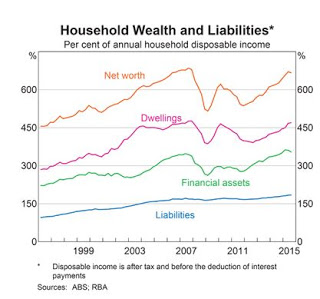

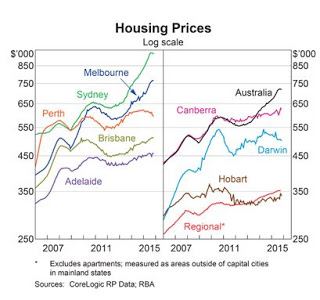

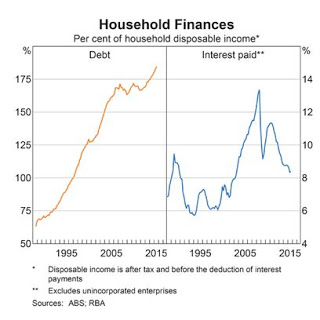

That place is Australia. It too had a housing boom and debt “bubble”. It too had a housing correction in 2008 that affected household balance sheets. This can be seen in the figures below:

Despite the balance sheet pains of 2008, Australia never had a Great Recession. In fact, it sailed through this period as one the few countries to experience solid growth. And, as Scott Sumner notes, it was also buffeted by a collapse in commodity exports during this time. If any country should have experienced a sharp recession in 2008 it should have been Australia.

So why did Australia’s balance sheet recession never happen? The answer is that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), unlike the Fed, got out in front of the 2008 crisis. It cut rates early and signaled an expansionary future path for monetary policy. It also helped that the policy rate in Australia was at 7.25 percent. This meant the central bank could do a lot of interest rate cutting before hitting the zero lower bound (ZLB). So between being more aggressive than the Fed and having more room to work, the RBA staved off the Great Recession.

This experience in Australia speaks to why the balance sheet recession view miss the deeper, more important problem behind depressions: the ZLB. Unlike the RBA, the Fed was slow to act in 2008 and that allowed the market-clearing or “natural” interest rate to fall below the ZLB. Had the Fed acted sooner or had it been able to keep up with the decline in the natural interest rate once it passed the ZLB, the Great Recession may not have been so great (See Peter Ireland’s paper for more on this point).

Here is how I made this point in my review of Atif Mian and Amir Sufi’s new book, House of Debt, in the National Review.

Why should the decline in debtors’ spending necessarily cause a recession?

Recall that for every debtor there is a creditor. That is, for every debtor who is cutting back on spending to pay down his debt, there is a creditor receiving more funds. The creditors could in principle provide an increase in spending to offset the decrease in debtors’ spending. But in the recent crisis, they did not. Instead, households and non-financial firms that were creditors increased their holdings of safe, liquid assets. This increased the demand for money. This problem was exacerbated by the actions of banks and other financial firms. When a debtor paid down a loan owed to a bank, both loans and deposits fell. Since there were fewer new loans being made during this time, there was a net decline in deposits [and thus] in the money supply. This decline can be seen in broad money measures such as the Divisia M4 measure. These developments—increase in money demand and a decrease in money supply—imply that an excess money-demand problem was at work during the crisis.

The problem, then, is as much about the excess demand for money by creditors as it is about the deleveraging of debtors. Why did creditors increase their money holdings rather than provide more spending to offset the debtors? …Mian and Sufi do briefly bring up a potential answer: the zero percent lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates.

The ZLB is a floor beneath which interest rates cannot go. This is because creditors would rather hold money at zero percent than lend it out at a negative interest rate. This creates a big problem, because market clearing depends on interest rates’ adjusting to reflect changes in the economy. In a depressed economy, firms sitting on cash would start investing their funds in tools, machines, and factories if interest rates fell low enough to make the expected return on such investments exceed the expected return to holding money. Even if the weak economy means the expected return to holding capital is low, falling interest rates at some point would still make it more profitable to invest in capital than to hold money. Similarly, households holding large amounts of money assets would start spending more if the return on holding money fell low enough to make household spending worthwhile. This is a natural market-healing process that occurs all the time. It breaks down when there is an increase in precautionary saving and a decrease in credit demand large enough to push interest rates to zero percent. If interest rates need to adjust below zero percent to spur creditors into providing the offsetting spending, this process will be thwarted by the ZLB.

It is the ZLB problem, then, rather than the debt deleveraging, that is the deeper reason for the Great Recession.

Australia never hit the ZLB. That is why it avoided the Great Recession. If we want to avoid future Great Recessions we need to find better ways to avoid or work around the ZLB.

Source: http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2016/01/the-balance-sheet-recession-that-never.html