| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Playing the lottery might be your smartest move

Read aguanomics http://www.aguanomics.com/ for the world’s best analysis of the politics and economics of water

David writes*

Voltaire called it a tax on stupidity. People who buy lottery tickets are often seen as stupid, naïve, or at the very least, (economically) irrational. They are often looked down upon because buying a lottery ticket would be an economically bad choice. This common belief is a logical outcome of expected utility theory: if the probability of winning times the pay-off is lower than the utility you lose by participating, you should not participate [pdf]. The obvious pay-off in the case of the lottery would be the prize money, and in that case, the probability of winning times the prize money is of course lower than the ticket prize, otherwise the lottery would not make any profit.

It is important to note for this theory however, that the pay-off is an expected utility value: people can never know how happy or unhappy they are going to be after something has happened, so they have to make an estimate of what the pay-off is going to be. That means that an economically rational choice is not necessarily the choice with the highest utility value, but the choice with the highest expected utility value based on the information with which the people make the choice.

Now often, playing the lottery is justified by a psychological factor, such as liking the thrill or wanting to have that incredibly small chance of never having to work again. There are however two reasons why even purely economically, it might be a rational choice. First of all, an information asymmetry plays a role. The extremely high pay-off is thrown into the face of the participants (and sadly also the people that do not participate) all the time, up to the point where you see an orange whale with a number on his back swim on your screen every 10 minutes when you are watching TV. The low probability is however just ‘low’, but a value is never really put on it. That means that people only know that it is about a huge number such as 20 million euros, and know that the probability is ‘low’, but not more than that. That means that their (unconscious) economic calculation might not show that buying the ticket is a bad idea, just that the ticket prize is relatively low and that the pay-off is huge, which might make it seem logical for them to participate. If the extremely low probability was thrown into their face equally as much as the high pay-off, perhaps many people would not participate.

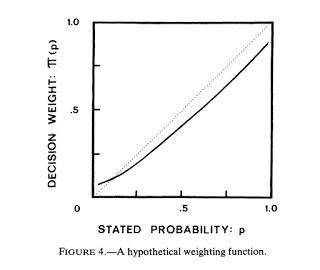

Second of all, Kahneman and Tversky have explained [pdf] why people put a disproportionately high weight on low probability risks. People might be incredibly scared of flying, terrorists, or sharks, even though the risks are miniscule. This disproportionate value changes the outcome of an (unconscious) economic calculation as well, up to the point where the risk times the pay-off plus the added weight might be bigger than the ticket prize. That means that the outcome of the calculation would be that it is economically interesting to play the lottery. Although this added value is not in any way paid back, the only thing that matters is that people add that weight when they make the choice, because as I explained in the beginning, rationality is not about the outcomes but rather the expected outcomes.

Bottom Line People might make an economically rational decision to play the lottery, because their lack of information and disproportionate weight of the choice cripple their (unconscious) economic calculation. This does not mean you should go out and buy a lottery ticket, just that people who are playing might not be as stupid as they are often made out to be.

* Please comment on these posts from my microeconomics students, to help them with unclear analysis, other perspectives, data sources, etc.

Source: http://www.aguanomics.com/2016/02/playing-lottery-might-be-your-smartest.html