| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

When to rely on markets and when politics?

Read aguanomics http://www.aguanomics.com/ for the world’s best analysis of the politics and economics of water The discipline of political-economy split in the 19th century (and very much so after World War II) when practitioners decided they needed to get more “scientific” (and thus mathematical-analytical) in their “understanding.”

The resulting evolution of both disciplines has been good news (clear theory! publications!) and bad news (irrelevance!), and there’s been a strong (and growing) countercurrent to re-integrate ideas from both disciplines. Two of the clearest efforts go by the names of “institutional” and “public choice” economics, i.e., the study of how rules and norms change over time and how “selfish” politicians affect public policy. Elinor Ostrom, not surprisingly, worked in both areas, along with her husband, Vincent, and many notable thinkers (Coase, North, Buchanan, Tullock, et al.)

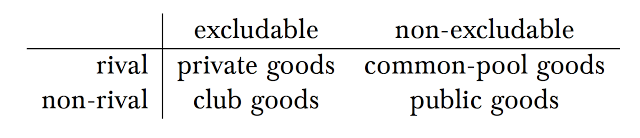

I use a political-economic framework all the time when thinking of how to manage goods. In this 2×2 grid, the columns refer to a good’s nature as a excludable or non-excludable.

The definition of “excludable” means that access to the good can be limited by rules, walls, etc. Such a characteristic also makes it easy to charge for access to the good. It is thus simple to recommend that these goods be managed in markets, using price as a means of rationing access (and encouraging production).

Non-excludable goods, in contrast, cannot be protected. It it therefore difficult to charge for access (or for damages) to those goods. (Negative externalities from using private goods are experienced in the commons.) That’s why non-excudable goods need to be managed via some sort of political mechanism that will impose penalties on those who use the goods “without permission.” Enforcement without access to police power (top down) or community approval (peer) is difficult, by definition.

(Rivalry means that one person’s use of the good leaves less for others. Non-rival goods are not “used” (depleted or contaminated) for one person when another enjoys it. Read more about these ideas in Chapter 1 of my book [free download])

These definitions should help you think about water governance, as it is perhaps preferable to use prices or markets to manage tap water or irrigation water, respectively, while it’s better to use policies and regulation to manage the commons of groundwater or water subject to pollution. Management in contradiction of these suggestions is possible, of course, but vulnerable to many types of failure, as abundant examples have shown.

Bottom Line Use the right tool — markets (voting) — when it comes to managing excludable (non-excludable) goods, respectively.

Source: http://www.aguanomics.com/2016/07/when-to-rely-on-markets-and-when.html