| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Guilty Pleasure: Offsetting Travel Emissions

Read aguanomics http://www.aguanomics.com/ for the world’s best analysis of the politics and economics of water

Martine writes*

For some people, air travel is a source of joy, entertainment, holiday-feelings or business-activities. However, this type of transportation also creates environmental pollution and contributes to climate change through its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which is less joyful. Keeping in mind the recently adopted Paris Agreement [pdf] where the United Nations decided to cut GHG emissions and keep global warming under 2°C, we might need to rethink our traveling behavior.

In an ideal world, people would be able to enjoy air travel while at the same time avoiding consequential environmental damage. Environmentally-conscious travelers will quickly point to the option to compensate for the environmental damage by offsetting their flight’s GHG emissions, of which carbon (CO2) is one. An organization, for example GreenSeat, will reduce the same amount of CO2-emissions elsewhere to get your carbon footprint to zero. A one-way flight from Amsterdam to Australia emits 11.200 tons of CO2 and can be compensated by donating 9.24 euros to renewable energy projects in Uganda, India or Cambodia. It’s cheap and feels like the right thing to do, so shouldn’t we all do this?

Before giving away the answer, I’ll first quickly explain the theory behind offsetting and the UN’s promise to keep global warming under 2°C. Please bear with me, our environment is at stake.

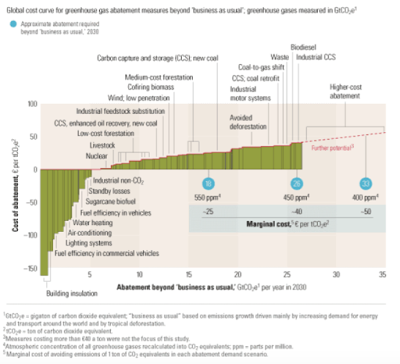

To keep their promise, the UN will need to invest billions of dollars to lower their CO2-emissions with at least 26 GtCO2 per year [pdf]. The price to abate 1 ton of CO2 depends on the country where the investment goes to, its phase of economic and social development and the already existing energy structures. For this reason, the ‘price’ of CO2 differs per country and industry, ranging between US$1.3 and US$524 per ton CO2. Intuitively, it is best to capture the cheapest forms of abatement first, the so-called ‘low-hanging fruits’, followed by other increasingly expensive ways to reduce emissions. In economic terms, this is called ‘diminishing marginal returns’, or ‘increasing marginal costs’. Figure 1 shows the costs of abatement and the reduced GtCO2 per year. You can see that some measures, like building insulation, are more efficient to reduce CO2 emissions than other higher cost abatement measures, like forestation or biodiesel.

|

| Figure 1: Global Cost Curve for Greenhouse Gas Abatement (Enkvist, Nauclér and Rosander, 2007) |

Of course, GreenSeat also knows this, and to keep the travel-offsetting price the cheapest possible for their environmentally-conscious consumers, they will invest in abatement at the low end of the curve in figure 1. And this is exactly the problem with flight-offsetting that I want to point out. Even though GreenSeat does reduce CO2-emissions with their investments, they do not contribute to the 26 GtCO2 per year reduction that is needed to keep global warming under 2°C, because their consumers emit the same amount of CO2 to the atmosphere during the flight that they bought the CO2-offset for. My biggest concern with this is that in the meantime, GreenSeat (or any other travel-offset organization/company) takes away the low-hanging fruits, the cheapest forms of abatement, while not solving the climate change problem. As the marginal costs of CO2 reduction increases, it will be even more difficult to invest efficiently to tackle global warming. Offsetting carbon emissions may be cheap and feels like the right thing to do, but environmentally-conscious travelers would do better by not traveling by plane at all.

* Please comment on these posts from my environmental economics students, to help them with unclear analysis, alternative perspectives, better data, etc.

Source: http://www.aguanomics.com/2017/02/guilty-pleasure-offsetting-travel.html