| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

The Myth of the Last Man

Former Ambassador, Human Rights Activist

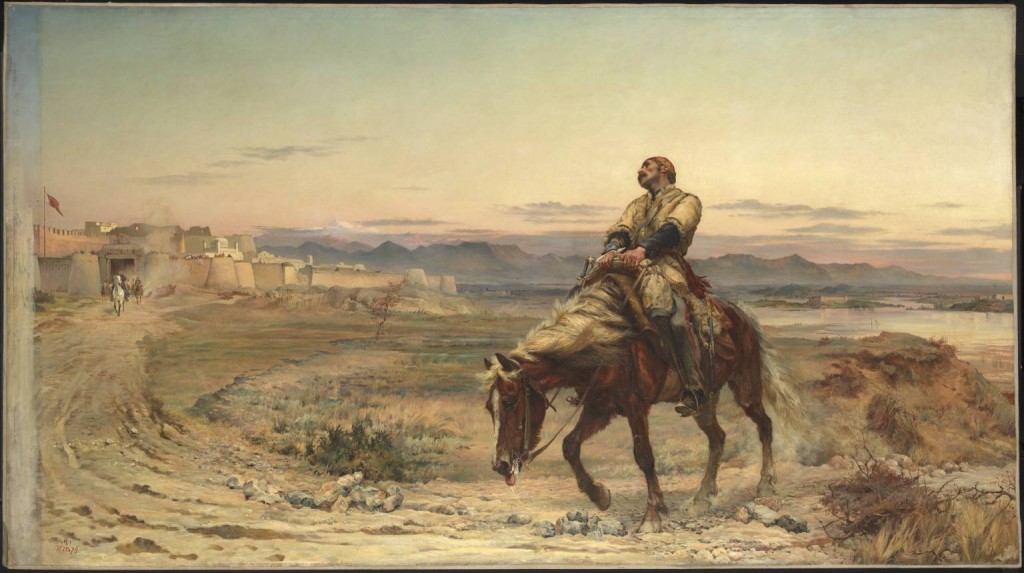

As the UK completes another military and political retreat from Afghanistan, it is time to revisit one of the most potent myths of the British Empire: the arrival at Jalalabad of Surgeon Brydon, wounded and on a shot-up dying nag, as the sole survivor of the Army of the Indus. It is a romantic scene that has been lovingly painted by scores of historians – and of course in a famous painting by Lady Butler.

But behind the myth, and never properly recorded by historians, is a disgraceful story of British officers leaving their men to die.

It is now generally understood and widely recorded that the army was not wiped out as completely as myth represents. So the retreat from Kabul saw the destruction of the Kabul force, not the Army of the Indus. One third of even the Kabul force survived, including at least 118 Europeans (Allen’s 117 plus Dr Brydon). In addition to this at least two European survivors of the Kabul force were to be killed by the British, fighting on the Sikh side in the British annexation of the Punjab. Their stories are not known. The high casualties of the Kabul force were not the result of a deliberate policy of extermination by Akbar Khan, but of vicious cold and the attacks of local tribesmen. The massacre was not a complete extermination for precisely that reason; undisciplined forces rarely kill everyone on a battlefield left hors de combat; it is hard physical work. Really thorough massacres of survivors are carried out by forces with a very disciplined command structure, like Henry V at Agincourt in 1415, like the Hanoverians at Culloden in 1746, or the Uzbek army at Andijan in 2005.

But if we dig deeper into the confusion and squalor of the retreat from Kabul, we find a very dark episode indeed. The escape of Dr Brydon was the result of a considered decision on the evening of 12 December of the mounted officers to desert their infantrymen – who were still fighting – leaving them to die while they made a break for Jallalabad on horseback. That is not to say the group of mounted men who abandoned the rest were exclusively infantry officers – some were cavalry, including sowars, horse artillery or staff officers – but many were infantry officers. The eyewitness accounts of this make it plain that the mounted men rode off despite specific pleas from the infantry not to desert them.

This can be discerned from the account of Dr Brydon himself:

“The confusion now was terrible; all discipline was now at an end, and the shouts of “Halt!” and “Keep back the cavalry!” incessant. The only cavalry were the officers who were mounted, and a few sowars…Just getting clear of the pass, I with great difficulty made my way to the front, where I found a large body of men and officers who, finding it perfectly hopeless to remain with the men in such a state, had gone ahead to form a kind of advance guard; but was we moved steadily on, whilst the main body was halting every second, by the time that day dawned, we had lost all traces of those in our rear.”

Even Brydon’s rather self-serving account states that there were calls for the horsemen to halt. This is much more graphic in the account of Sergeant-Major Lissant of the 237th Native Infantry, who was of course one of those abandoned on foot.

“The rear kept calling on the men in front to halt, while the officers were urging the expediency of pushing on and losing no time, as they said could we reach Gandamack by daylight we should be safe.

This continued for some time, some of the men halting, others pushing on as requested, till the cries from the rear became more loud and frequent to halt in front. The men in front then said, “The officers seem to care but for themselves, let them push on if they like, we will halt till our comrades in the rear catch up.

From this point, some of the officers went on, as all regularity seemed at an end; every man determined to act for himself”

This puts a very different complexion indeed on Dr Brydon’s “heroic” ride to Jallalabad. The fact that the officers who tried to save their lives by abandoning their men mostly failed, does not make this any less a stain in the records of the British army.

It is a fascinating fact that the abandonment of their men by the mounted officers was observed by the Afghans, and the knowledge has survived down to modern times, forming part of the underlying Afghan tribal dislike for the British which caused so many difficulties in the current long occupation. In 1973, collecting folklore stories of the First Afghan War, the ethnographer Louis Dupree was told near Gandamack: “But they did not all die on the hill, because many of the officers on horseback rode away from their men.”

It is also worth noting that, despite his being adopted as a hero by Victorian politicians and media seeking to spin a glorious national myth, a pall of suspicion hung around Brydon in India for decades. His biographer John Cunnignham records that but fails to give the full facts as to why.

The Kabul retreat was not in reality unprecedented. Monson’s repeat before Holkar in 1804, with Brown’s related retreat to Agra, caused about the same number of casualties among British troops. In that retreat too the mounted British officers simply deserted their men. As James Skinner recorded:

“I saw about 1,500 men march into camp with colours flying under the command of a British sergeant, with a great number of soobhadars and jemadars of native corps. These heroes had kept their ground after all their officers had left them. The poor sergeant was never noticed.”

[I am currently going through the heartbreaking process of reducing Sikunder Burnes from 260,000 to 180,000 words for publication. I am posting some of the more interesting bits that have to be shed on to this blog. Skinner, Like Burnes, was from Montrose. William Brydon was from Fortrose].

Source: https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2014/12/the-myth-of-the-last-man/