| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

Can Anoles With Differently Shaped Genitals Interbreed?

We’ve had a number of posts in the last few months discussing new species described on the basis of difference in the shape of their hemipenes (most recently here). And, because such descriptions have been based on morphological data without any corroborating molecular data, we’ve wondered whether, in fact, these forms are genetically isolated and whether they are capable and willing to interbreed given the opportunity.

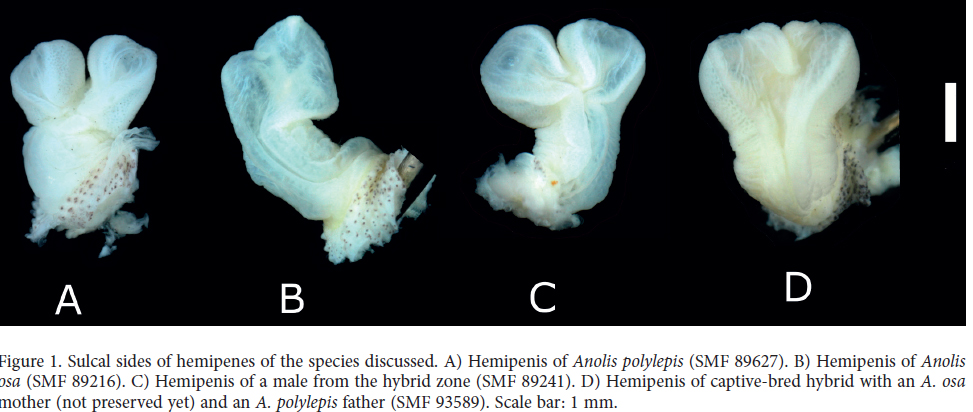

Köhler et al. have taken the next step and attempted to answer these questions in the case of Anolis osa, which was split from the otherwise nearly indistinguishable A. polylepis on the basis of its hemipenial shape (figures A and B above). They find that in the lab, members of the two putative species can interbreed and produce offspring, at least some of which are apparently fertile (although the details of this are hard to fathom). Moreover, in the field, hybrid looking individuals are found where the two forms meet (Figure C above), and the hemipenes of these individuals are similar to the intermediate-looking tallywhackers of hybrids bred in the lab (Figure D above).

Most interestingly, females of the species seem to differ in the shape of their reproductive tract in a manner parallel to the differences among the males. In particular, female A. polylepis have longer vaginal tubi, corresponding to bilobed structures of their males, whereas female A. osa‘s tubes are shorter. One possible explanation for these differences is the old “lock-and-key” hypothesis that male and female genitals are perfect matches, thus preventing interspecific matings. This idea has fallen out of favor in recent years, and the authors discount it. Rather, they favor more recent ideas that such differences evolve by sexual selection, females preferring males whose genitals phenotypically match their own. Here’s their theory:

Most interestingly, females of the species seem to differ in the shape of their reproductive tract in a manner parallel to the differences among the males. In particular, female A. polylepis have longer vaginal tubi, corresponding to bilobed structures of their males, whereas female A. osa‘s tubes are shorter. One possible explanation for these differences is the old “lock-and-key” hypothesis that male and female genitals are perfect matches, thus preventing interspecific matings. This idea has fallen out of favor in recent years, and the authors discount it. Rather, they favor more recent ideas that such differences evolve by sexual selection, females preferring males whose genitals phenotypically match their own. Here’s their theory:

“Considering the available evidence, we assume that sexual selection by female choice (Eberhard 1985, Eberhard 1996) is the most plausible explanation of the peculiarly rapid divergent evolution of genital morphology between A. polylepis and A. osa. Assuming that females are able to discriminate between mates with different hemipenial morphologies and that insemination success varies depending on female preference, any male performing a superior stimulus would benefit from advantages in reproductive success. Females that prefer mates performing this stimulus in turn would be favoured by producing favourable male offspring. Small initial changes in female preference of hemipenial morphology thereby could give rise to a runaway process as proposed by Fisher (1958). However, in what is presumably a secondary contact zone, “mismatched” mating events occur due to the absence of effective premating isolating mechanisms and the reproductive success of such mating events is apparently greater than zero. Differences in the functionality of hemipenial morphology would affect reproductive success of males mainly or only in situations of direct competition for female gametes, and this functionality would be dependent on female genital or sensorial conditions. If females tend to be philopatric (which is implied by the structure found in the sequences of mitochondrial DNA), a male entering the contact zone would predominantly encounter females that prefer the other hemipenial morph and be disadvantaged with regard to their reproductive success. Depending on how strong this sexual selection works, it could even maintain the geographical integrity of genital morphology against homogenising effects from a male-biased gene flow (Stenson et al. 2002).”

So, where does this lead us? Combining morphological, molecular, and behavioral studies is definitely the way to go in evaluating the significance of hemipenial morphology. I am a little unclear about what to make of their results. Clearly, the differences don’t prevent interbreeding, but whether they are a marker of evolutionary lineages, distinct enough to considered different species, would seem to require more detailed study of genetic exchange. This is definitely a good first step in that direction.

Source: