| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

The Ape In the Trees

I'd guess that few people outside of primate paleontology are familiar with the story of The Ape in the Tree. It's one of those stories in paleontology that never gets old—even if you've heard Alan Walker, one of the story's main unravelers and my Ph.D. advisor, tell it many times. Now, thanks to a new discovery by our team, out today in Nature Communications, we've got a new story to tell alongside it: The Ape in the Trees.

|

| Alan Walker in the mid 80s excavating at the Kaswanga Primate Site, Rusinga Island, Kenya |

Because it's a juicy one, let's recount the ol' Ape in the Tree first.

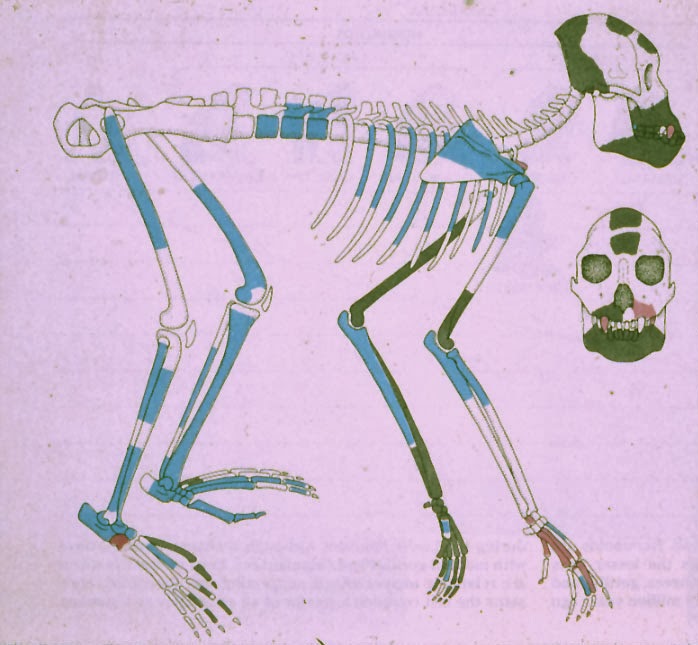

The “Ape” refers to Proconsul, a genus of fossil hominoids from the earliest part of the ape radiation. Proconsul remains are preserved in deposits down at the early part of the Miocene epoch at sites in Kenya and Uganda. These animals weren't doing much of any brachiation, suspension, or knuckle-walking in the trees or on the ground like extant gibbons, siamangs, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos. They were what we call generalized arboreal quadrupeds, moving about the trees by relatively slow but strong grasping with their hands and feet, and without the aid of a tail for balance. Body size estimates across the few known species range from 9-90 kg (20-200 pounds), but little in the way of functional anatomical differences (which are translated into behavioral differences) are apparent.

|

| Proconsul skull discovered by Mary Leakey on Rusinga Island in the late 1940s. |

|

| Mary's skull was commemorated as a postage stamp. |

In the story, “Ape” specifically refers to just one partial skeleton found at R114 on Rusinga Island, Kenya.

|

| KNM-RU 2036. Proconsul partial skeleton from site R114. The green bits are the additional parts found by Walker and colleagues decades after the initial discovery marked in blue. |

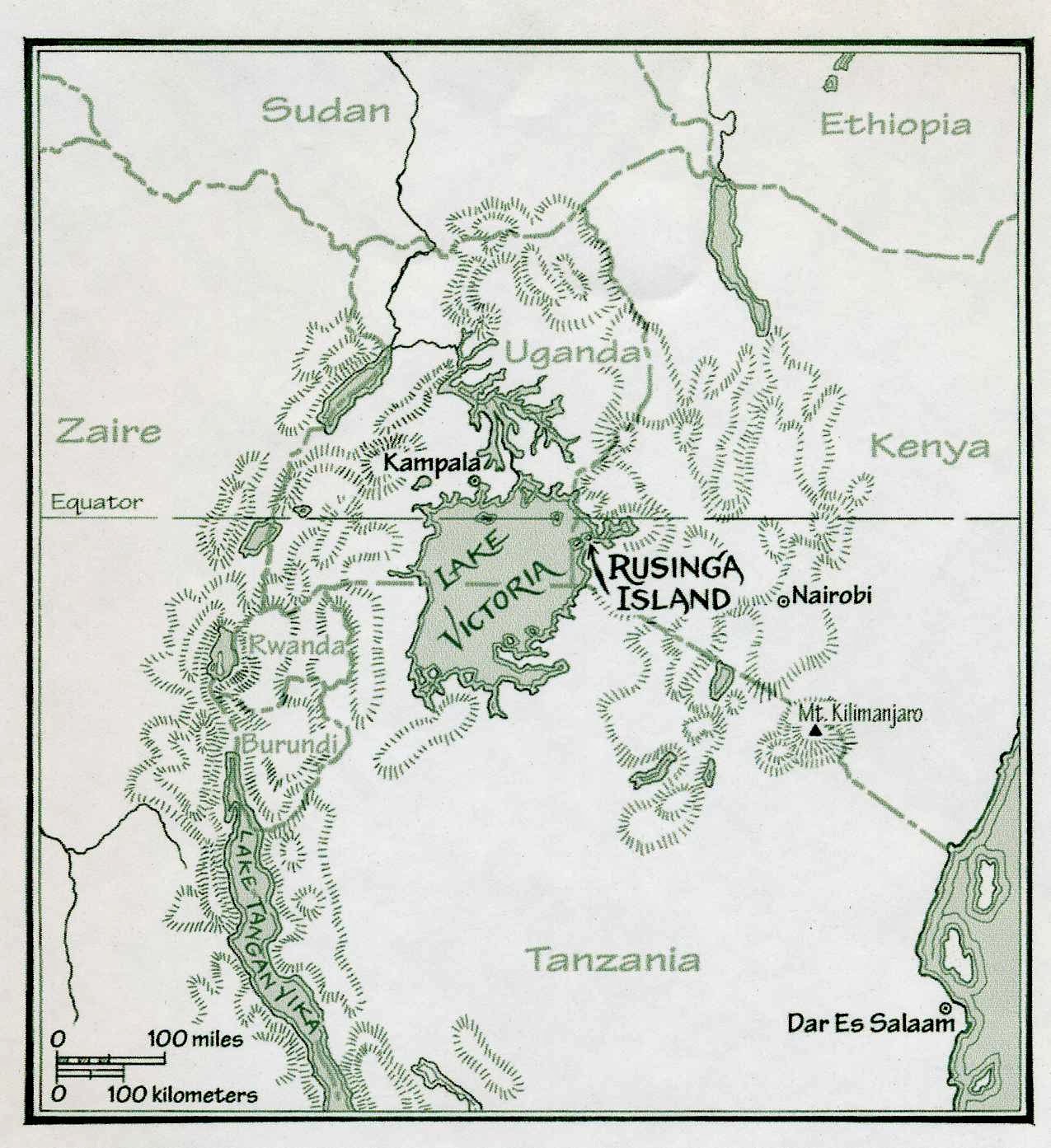

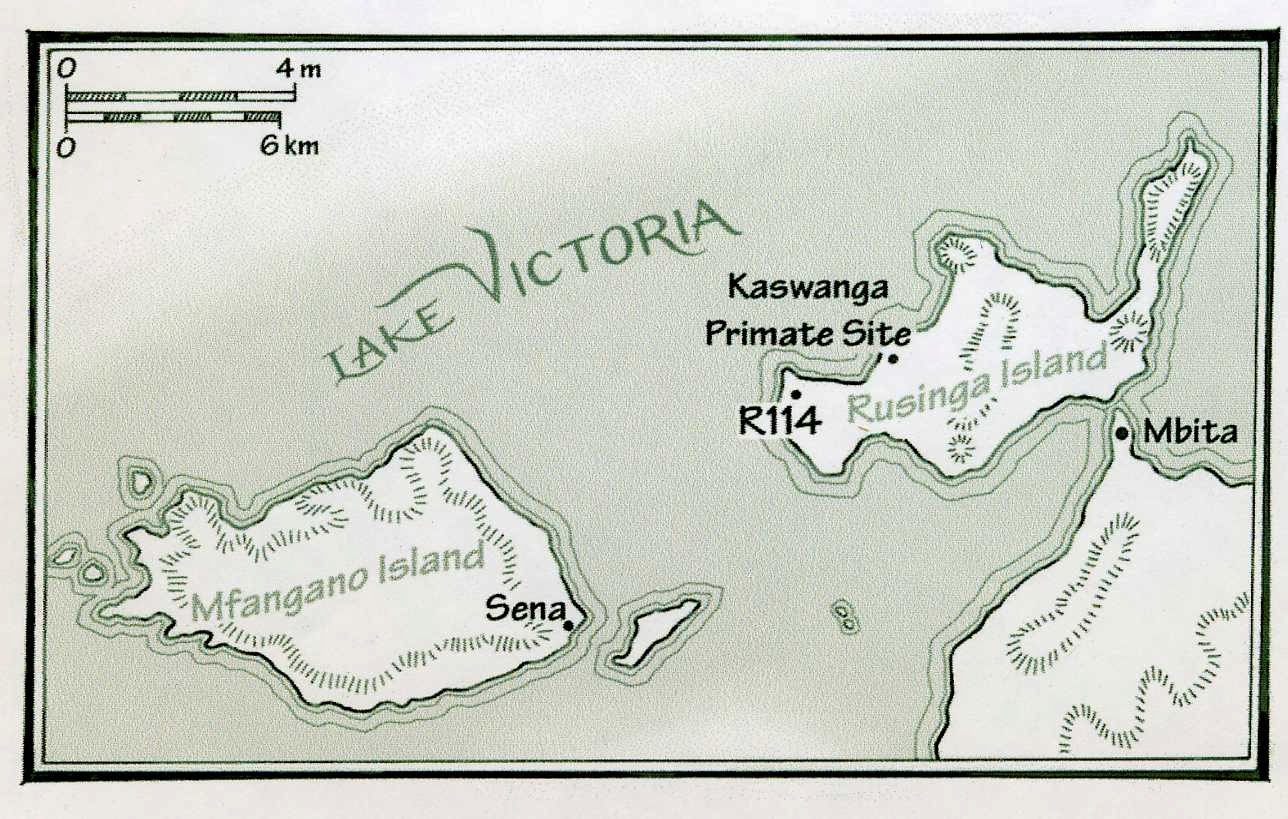

Rusinga's an island in Lake Victoria connected by a short human-built causeway to the mainland, but the lake, and hence the ability for Western Kenyan land to become surrounded by its water, is fairly recent, within the last 2 million years or so, and it's fluctuated greatly in depth ever since. Here's how it looks now:

|

| (c) Shipman and Walker |

|

| (c) Shipman and Walker |

20-18 million years ago, at the time of Proconsul, Rusinga Island's terrain was part of the land flanking the then-active Kisingiri Volcano which is just south of Mbita and out of frame of the map above. It's in large part thanks to the volcanic deposits that such wonderful preservation occurs on Rusinga.

People have been studying Proconsul for nearly 90 years (with the initial find at a limestone quarry in Koru, Western Kenya). And they've been studying the fossils and rocks of Rusinga Island, the site which has produced the most Proconsul fossils, for nearly as long.

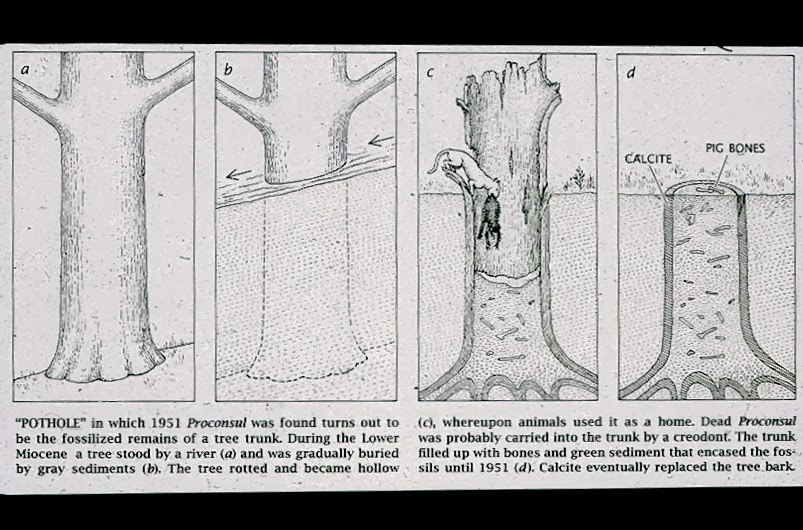

Site R114 was recognized early on in the scientific history of Rusinga Island. A few curious circular deposits of a different rock composition than the surrounding matrix (and containing interesting fossils including Proconsul KNM-RU 2036, the blue bits on the figure above) were hypothesized to be potholes. This was the explanation that held until the mid 1980s when Alan Walker and his friends started poking around in the Rusinga collections in Nairobi. Walker noticed some Proconsul bones collected by Louis Leakey and colleagues from Rusinga Island had been misidentified as other animals. This inspired a joint team from Walker's university, the Johns Hopkins University, and the National Museums of Kenya to go to Rusinga Island to re-examine sites there. The expeditions were successful. They recovered more Proconsul bones to join the partial skeleton KNM-RU 2036 found at site R114; the green bits on the figure above). But what's even more exciting was their investigation of this pothole idea.

They simply (I meant that in spirit, not sweat) dug down at the edges of the pothole and saw that, instead of finding a basin shape in the ground like a good pothole, the edges actually got wider and wider the deeper they dug.

|

| The pothole that wasn't. (R114, Rusinga Island) |

Instead of a pothole, this curious fossil-filled feature appears to be a fossil tree trunk that was both filled in by sediment and fossils but also buried deep by surrounding sediment. To explain how the Proconsul and other creatures, like a rabbit and an ungulate, were also preserved, Walker and colleagues surmised that it was once hollowed out and used by a carnivore, like a creodont, as a den.

|

| Figure from Alan Walker and Mark Teaford (1989) The Hunt for Proconsul. Scientific American 260(1): 82. Diagram drawn by Tom Prentiss. Also reproduced in Walker and Shipman’s 2005 book The Ape in the Tree. |

So there you have it… that's “The Ape in the Tree” in a nutshell… you can read much more about it in the book of the same name.

|

| link |

Now, onto the brand new story of The Ape in the Trees…

A team of us has been working the sites on Rusinga and nearby Mfangano Island, annually or more, since 2006. We've been fortunate to collaborate internationally and to share this work with many undergraduate and graduate students too.

|

| Systematic survey at site R107 in 2011 |

We've been exceedingly lucky to have a geologist on our team, Dan Peppe, who is also a paleobotanist. This is because there are not just fossil tree trunks but exquisitely preserved leaves.

|

| Figure from “A morphotype catalog and paleoenvironmental interpretations of early Miocene fossil leaves from the Hiwegi Formation, Rusinga Island, Lake Victoria, Kenya” [link]

|

And—as discovered at a particularly rich site by Peppe's doctoral student, Lauren Michel—there are also well-preserved root systems. And these are located among fossil tree trunks, within nicely preserved paleosols (soils) that happen to contain fossils of Proconsul and another primate Dendropithecus.

|

| Lauren Michel and Dan Peppe hard at work. |

That's what we've published today in Nature Communications. (Note: The embargo is lifted and I'll return and add link to paper when I can.)

|

| Reconstruction of site R3, this fossil forest containing fossil Proconsul (fore) and Dendropithecus (higher up) by artist Jason Brougham. |

This time, then, the story's not about an ape skeleton actually inside a tree, but it's about an ape (and other creatures) dying in a preserved fossil forest of trees. The root systems and distance between trunks points to a closed-canopy forest, meaning that the arboreal creatures like Proconsul and Dendropithecus needn't come down to the ground to travel and that the ground was most likely very shady, with an ecosystem that reflected it. Further, the fossil leaf morphologies point to a wet and warm forest. All consistent with what many primates, especially apes, prefer for habitat today. What's more, this habitat reconstruction jibes so nicely with the behavioral interpretations we've made for Proconsul based on anatomy.

We started this long-term project at such historically well-known sites not just to find more of the ancient fossil apes they're famous for (which we have!), but because we wanted to describe the paleoenvironments in which they lived, died, and evolved. The findings in this paper are more than I dared to dream would come from our work already. It's some of the best evidence linking ape to habitat that we could ask for. It really speaks to the power of collaboration and perseverance.

|

| Glorious fossils. Not too shabby of a campsite either. |

To get a sense of what we do at Rusinga, here's a nice film that a crew from the American Museum of Natural History put together about our work.

Science Bulletins: Expedition Rusinga – Uncovering Our Adaptive Origins from AMNH on Vimeo.

Our work's also featured in the Hall of Human Origins at the AMNH, including a fun interactive exhibit that shows us doing many fieldwork type things like sieving endless piles of dirt.

And here's a peek at the ape tail loss story that Proconsul tells, which will be part of Neil Shubin's three-part series in April on PBS called Your Inner Fish.

Source: http://ecodevoevo.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-ape-in-trees.html