| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Breakthrough in Energy Harvesting Could Power ‘Life on Mars’

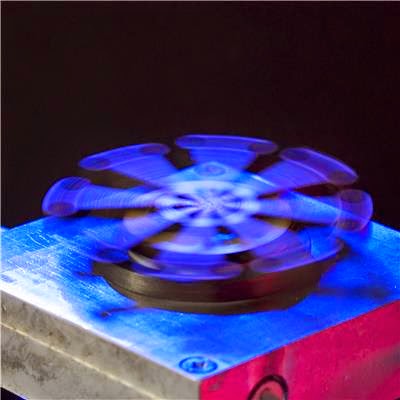

The technique, which has been proven for the first time by researchers at Northumbria, has been published in the prestigious journal Nature Communications.

Credit: Northumbria University

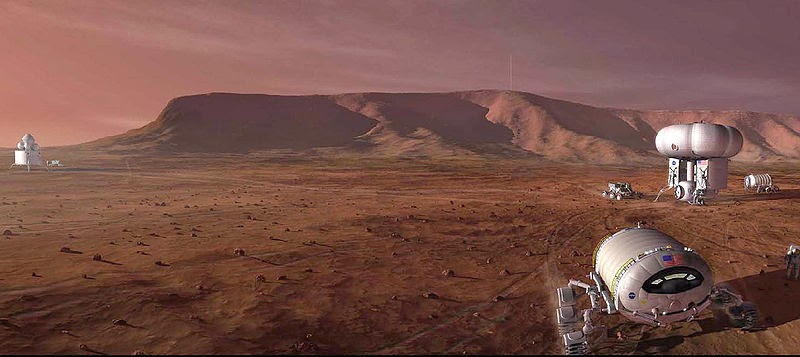

Dry ice may not be abundant on Earth, but increasing evidence from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) suggests it may be a naturally occurring resource on Mars as suggested by the seasonal appearance of gullies on the surface of the red planet. If utilised in a Leidenfrost-based engine dry-ice deposits could provide the means to create future power stations on the surface of Mars.

One of the co-authors of Northumbria’s research, Dr Rodrigo Ledesma-Aguilar, said: “Carbon dioxide plays a similar role on Mars as water does on Earth. It is a widely available resource which undergoes cyclic phase changes under the natural Martian temperature variations.

“Perhaps future power stations on Mars will exploit such a resource to harvest energy as dry-ice blocks evaporate, or to channel the chemical energy extracted from other carbon-based sources, such as methane gas.

“One thing is certain; our future on other planets depends on our ability to adapt our knowledge to the constraints imposed by strange worlds, and to devise creative ways to exploit natural resources that do not naturally occur here on Earth.”

The team at Northumbria believe one of humanity’s biggest challenges this century will be finding new ways to harvest energy, especially in extreme environments. It was this challenge which led them to develop their proposed Leidenfrost Engine.

He said: “The working principle of a Leidenfrost-based engine is quite distinct from steam-based heat engines; the high-pressure vapour layer creates freely rotating rotors whose energy is converted into power without the need of a bearing, thus conferring the new engine with low-friction properties.”

As well as potentially making long-term space exploration and colonisation more sustainable, the unique, low-friction nature of this engine could have other exciting applications, according to Executive Dean for Engineering and Environment, Professor Glen McHale.

Professor McHale, who also worked on the new research with Dr Wells and Dr Ledesma-Aguilar, said: “This is the starting point of an exciting avenue of research in smart materials engineering. In the future, Leidenfrost-based devices could find applications in wide ranging fields, spanning from frictionless transport to outer space exploration.”

Contacts and sources:

Northumbria University

Source: http://www.ineffableisland.com/2015/03/breakthrough-in-energy-harvesting-could.html