| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Missing Link Found: Jaw of New Human Found in Ethiopia

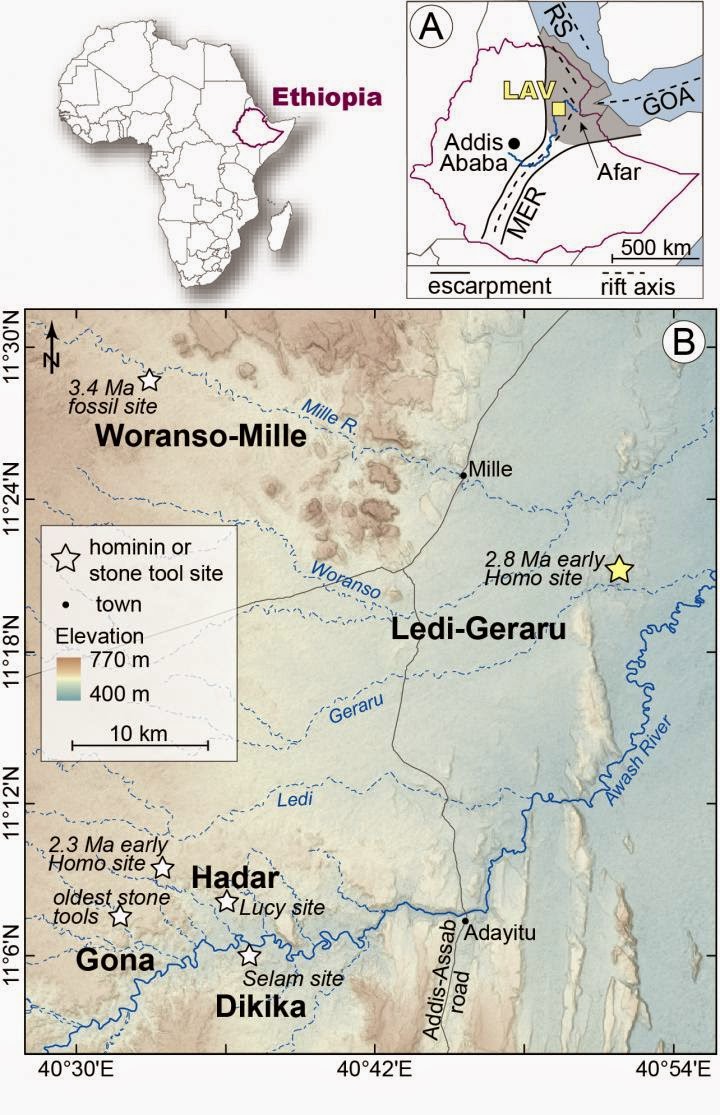

The jaw predates the previously known fossils of the Homo lineage by approximately 400,000 years. It was discovered in 2013 by an international team led by Arizona State University scientists Kaye E. Reed, Christopher J. Campisano and J Ramón Arrowsmith, and Brian A. Villmoare of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

A caravan moves across the Lee Adoyta region in the Ledi-Geraru project area near the earlyHomo site. The hills behind the camels expose sediments that are younger than 2.67 million year old, providing a minimum age for the LD 350-1 mandible.

Credit: Erin DiMaggio

“In spite of a lot of searching, fossils on the Homo lineage older than 2 million years ago are very rare,” says Villmoare. “To have a glimpse of the very earliest phase of our lineage’s evolution is particularly exciting.”

In a report in the journal Nature, Fred Spoor and colleagues present a new reconstruction of the deformed mandible belonging to the 1.8 million-year-old iconic type-specimen of Homohabilis (“Handy Man”) from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. The reconstruction presents an unexpectedly primitive portrait of the H. habilis jaw and makes a good link back to the Ledi fossil.

Global climate change that led to increased African aridity after about 2.8 million years ago is often hypothesized to have stimulated species appearances and extinctions, including the origin of Homo. In the companion paper on the geological and environmental contexts of the Ledi-Geraru jaw, Erin N. DiMaggio, of Pennsylvania State University, and colleagues found the fossil mammal assemblage contemporary with this jaw to be dominated by species that lived in more open habitats–grasslands and low shrubs–than those common at olderAustralopithecus-bearing sites, such as Hadar, where Lucy’s species is found.

“We can see the 2.8 million year aridity signal in the Ledi-Geraru faunal community,” says research team co-leader Kaye Reed, “but it’s still too soon to say that this means climate change is responsible for the origin of Homo. We need a larger sample of hominin fossils, and that’s why we continue to come to the Ledi-Geraru area to search.”

The research team, which began conducting field work at Ledi-Geraru in 2002, includes:

Erin N. DiMaggio (Pennsylvania State University), Christopher J. Campisano (ASU Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change), J. Ramón Arrowsmith (ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration), Guillaume Dupont-Nivet (CNRS Géosciences Rennes), and Alan L. Deino (Berkeley Geochronology Center), who conducted the geological research

Faysal Bibi (Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science), Margaret E. Lewis (Stockton University), John Rowan (ASU Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change), Antoine Souron (Human Evolution Research Center, University of California, Berkeley), and Lars Werdelin (Swedish Museum of Natural History), who identified the fossil mammals

Kaye E. Reed (ASU Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change), who reconstructed the past habitats based on the faunal communities

David R. Braun (George Washington University), who conducted archaeological research

Brian A. Villmoare (University of Nevada Las Vegas), William H. Kimbel (ASU Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change), and Chalachew Seyoum (ASU Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change, and Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Addis Ababa), who analyzed the hominin fossil

The Ledi-Geraru Research Project is based in the Institute of Human Origins (IHO) at Arizona State University. IHO is one of the preeminent research organizations in the world devoted to the science of human origins. A research center of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, IHO pursues an integrative strategy for research and discovery central to its over 30-year-old founding mission, bridging social, earth, and life science approaches to the most important questions concerning the course, causes, and timing of events in the human career over deep time. IHO fosters public awareness of human origins and its relevance to contemporary society through innovative outreach programs that create timely, accurate information for both education and lay communities.

Contacts and sources:

William Kimbel, Arizona State University

Brian Villmoare (in Las Vegas, Nevada)

Erin DiMaggio (in State College, Pennsylvania)

Source: http://www.ineffableisland.com/2015/03/missing-link-found-jaw-of-new-human.html