| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

The Noisiest Places in the Ocean

According to research accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, the underwater noise levels are much louder than previously thought, which leads scientists to ask how the noise levels influence the behavior of harbor seals and whales in Alaska’s fjords.

Pettit conducted the study with researchers from the University of Texas at Austin; the University of Washington, Seattle; and the United States Geological Survey.

Credit: Jeffrey Nystuen.

The team used underwater microphones to listen and record the average noise levels in three bays whose fjords have glaciers that flow into the ocean – Icy Bay, Alaska; Yakutat Bay, Alaska; and Andvord Bay, Antarctica. All of the fjords have many icebergs where chunks of the glacier fell or calved into the water.

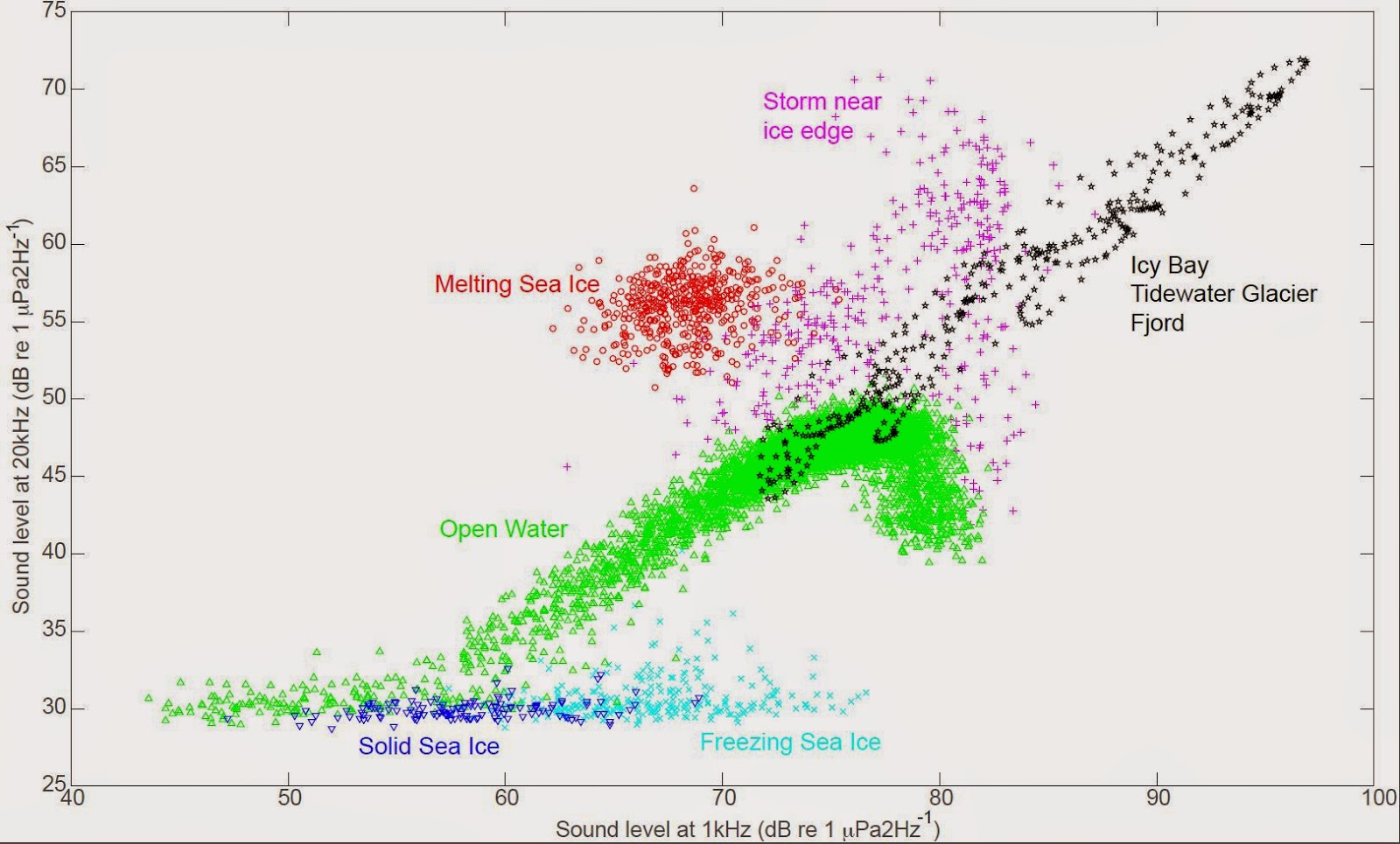

The researchers found that the average underwater noise level in these fjords was higher than any other source of ocean noise that has been measured so far including noise from weather, the movement and communication of fish, and human-generated noise from shipping and sonar devices. The team measured noise levels between 300 and 20,000 Hz, which is most of a human’s hearing range.

Glacier calving contributed to some of the noise, but the loud sounds were short-lived. When looking at overall noise levels for a long period of time, Pettit said it was the consistent melting of ice from the glacier and its icebergs that was the real noise generator. This is because the air trapped within the glacier ice escapes rapidly as it melts into saltwater, forming bubbles in the water that pop as they pinch off from the ice.

Pettit said their findings raise questions about how the underwater noise in the fjords will affect animals as climate change first increases the rate at which glaciers melt into the ocean water and then stops the process altogether as the glaciers shrink and retreat onto land.

Credit: Erin Pettit

Credit: Erin Pettit

Credit: Erin Pettit

She said fjords with glaciers are foraging hotspots for seabirds and marine mammals as well as important breeding locations for harbor seals. One possibility, she said, is that the seals use the underwater noise to help conceal them from killer whales, which rely on listening to locate the seals. As glaciers retreat onto land, the seals would lose the acoustic camouflage, which might explain why harbor seal populations are declining in fjords where glaciers have retreated onto land, she said.

She said further studies are needed to investigate the relationship between the underwater noise levels and the fjord ecosystem. The team will continue listening to glaciers to see if they can develop a method of predicting glacier melt based on the underwater sounds.

Contacts and sources:

The American Geophysical Union

Source: http://www.ineffableisland.com/2015/03/the-noisiest-places-in-ocean.html