| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Are You Genetically More Hunter Than Farmer?

More local adaptations in European genes were contributed by Stone Age hunters than farmers.

Modern humans have adapted to their local environments over many thousands of years, but how genetic variation contributed to this adaptation remains debated. Using genomes from humans that lived between 45,000 and 7,000 years ago, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig have shown that adaptation to local environments has resulted in genetic variants reaching high frequencies in European groups.

Credit: © Vyacheslav Andreev

This image shows a family of Neanderthals. The Neanderthals lived in the Northern and Western areas of Eurasia, during the Pleistocene epoch, in the time of the last Ice Age.

Credit: NASA/JPL

Using the genome of a 45,000 year old early modern Eurasian from Ust’-Ishim, researchers from the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig investigated the few genetic variants that have large frequency differences between Africans and non-Africans. “When we first heard about the Ust’-Ishim genome we got immediately excited. This individual is extremely useful in that it provides direct information on the genetics of a population that had experienced the out-of-Africa migration, but had not had much time to adapt to Eurasian environments”, says Aida Andrés, who led the scientific team.

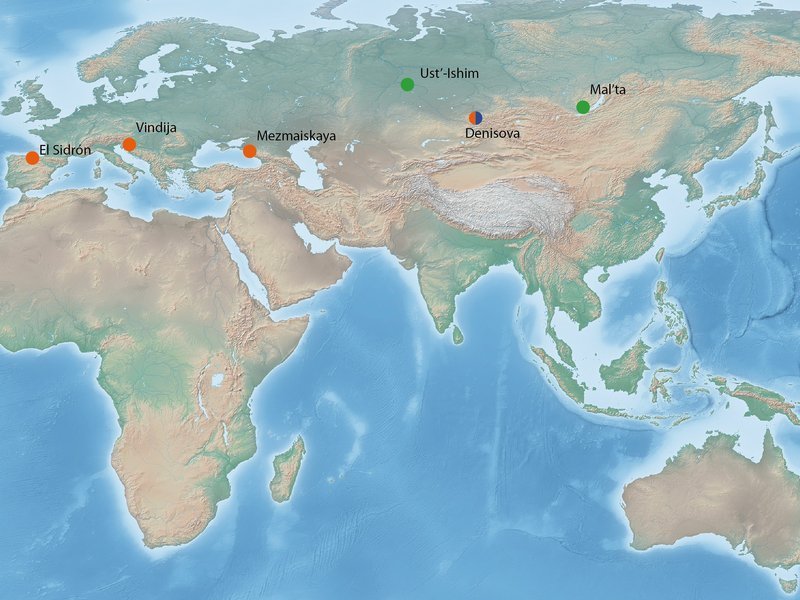

Map of Pleistocene fossils with published nuclear DNA (orange: Neandertals, blue: Denisovans, green: modern humans).

Credit; © MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology/ Bence Viola

The genomes of additional ancient Europeans provided more detail on local adaptation in Europe. The team showed that an early hunter-gatherer carried more variants that have increased quickly in frequency in Europe than an early farmer. “It is quite striking that, while the Neolithic farming revolution brought a lifestyle to Europe that still persists today, the hunter-gatherers provided the majority of genetic adaptations to the local European environment”, says Felix Key, PhD student at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig and first author of the paper.

Andrés sees great potential for this approach in the future: “Combining modern and ancient genomes improves our ability to understand local adaptation. The resolution of studies like ours will keep improving with the growing availability of high-quality ancient genomes.” She predicts that “With additional data we are likely to find similar evidence of genetic adaptations in other continents, too”.

Contacts and sources:

Felix M. Key

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

Source: http://www.ineffableisland.com/2016/03/are-you-genetically-more-hunter-than.html