| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Lady Woodward’s tablecloth

Between 1894 and 1944, Maud and Arthur Smith Woodward welcomed countless eminent scientists into their homes in Kensington and Haywards Heath, Sussex. Arthur’s position as curator of the Geology Department of the British Museum of Natural History (now the Natural History Museum) meant that Maud was hostess to a huge range of famous names, and she developed an unconventional form of a ‘visitors’ book’ to record their visit.

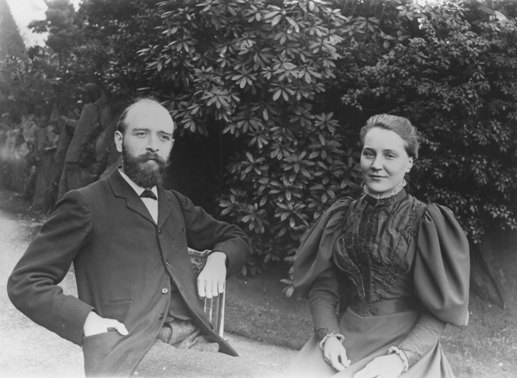

Maud and Arthur Smith Woodward, pictured in 1887 (source: https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Geoscientist/Archive/April-2014/King-of-the-fishes)

Lower left corner of the tablecloth that includes signature of Arthur Smith Woodward (blue). Image from ‘Lady Smith Woodward’s Tablecloth’, SP 430, 89-111

Guests were asked to sign a linen tablecloth in pencil, which she then skilfully embroidered in fine strands of coloured silks, having first asked the signatories to choose their preferred colour’, says Angela Milner in a paper from the Geological Society’s recently published ‘Arthur Smith Woodward: His Life and Influence on Modern Vertebrate Palaeontology.’

The information on how the tablecloth was created comes from Mrs Ruth Niblett, the Woodwards’ granddaughter, passed down from her mother, Mrs Margaret Hodgson.

In all, there are 342 signatures representing 331 people. Eight are signed in Cyrillic, one each in Japanese and Greek. Each corner was given to a different speciality – the corners for palaeontologists and geologists are naturally more densely packed.

Famous Names

Numerous famous names are recorded on the tablecloth. Apart from Smith Woodward himself, signatories include Catherine Raisin (1855-1945), Professor of Geology at Bedford College, who featured in our recent blog post about the struggle for women to gain admittance to the Geological Society as Fellows.

Marie Stopes (1880-1958), though now famous primarily for her work in family planning, was Lecturer in Palaeobotany at the University of Manchester between 1904 and 1911. (Stopes is a regular feature on our blog – read more about her palaeobotany here, and her turbulent love life here…)

Two other names stand out – as much for their association with a notorious case, as for their scientific credentials.

Tucked in amongst the scrawled names of palaeontologists are those of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) and Charles Dawson (). Both are now inextricably linked to one of the most infamous scientific frauds in history – the mystery of Piltdown Man.

The Missing Link

In 1912, news of the discovery of ‘Piltdown Man’ in a gravel pit in Sussex caused a sensation in the scientific press. The skull, with its ape like jaw and human cranium, appeared to be a ‘missing link’ between apes and man.

Dawson, de Chardin and Woodward himself were all involved in subsequent excavations, but it was Dawson himself who first uncovered the find. An amateur scientist, his eclectic interests had led him to a miscellany of finds- from Roman statuettes to Neolithic hand axes to a petrified toad inside a flint nodule. Piltdown man – Eoanthropus dawsoni (“Dawson’s dawn-man”) – was his greatest discovery. It was also – as was revealed in 1953 – a fake.

Though never proven, Dawson was almost certainly responsible for the fraud. Both de Chardin and Woodward – as well as a whole cast of characters – have been accused of involvement, but there is no evidence that they were anything other than victims of Dawson’s hoax – not least beause, following the latter’s death in 1916, no further finds were made at the site.

Arthur Smith Woodward

Woodward’s scientific achievements have been somewhat overshadowed by the scandal of Piltdown Man – of which he was almost certainly an unwitting victim. But there is no doubt that his contributions elsewhere were enormous – as our new publication aims to demonstrate.

As well as the NHM’s longest serving Keeper of Geology, he was the foremost world expert on fossil fish, and received many awards for his contributions to palaeoichthyology, including the Geological Society’s Lyell and Wollaston medals.

type specimen of Gyrodus frontatus Agassiz, Lithographic Limestone, Kelheim, Bavaria. Egerton Collection. (© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.)

He met Maud through her zoologist father. After their marriage, she accompanied him on most of his travels, which she described as ‘a lifetime’s passionate journeying for knowledge and more knowledge of the subjects he studied and the men who had gone before him.’

The tablecloth’s fate

Some years after Woodward’s death in 1944, his wife gifted the tablecloth to the American palaeontologist George Gaylord Simpson, a family friend. In 1951, Simpson gave it to the American Museum of Natural History, where it lay forgotten for some years.

It returned to London in 1977, and after restoration at the Victoria & Albert Museum, was displayed on the fourth floor of the Palaeontology Building of the Natural History Museum in 1987 – a fitting home for a fascinating relic of 19th and early 20th century palaeontology.

Further reading: Arthur Smith Woodward: His Life and Influence on Modern Vertebrate Palaeontology SP v. 430, 2016, edited by Z. Johanson, P. M. Barrett, M. Richter and M. Smith.

![]()

Source: http://blog.geolsoc.org.uk/2016/03/15/lady-woodwards-tablecloth/