| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

Cuban Anolis porcatus introduced to Brazil (perhaps through Florida?)

Several anole species have become established outside of their native ranges as a result of human-mediated transportation, being introduced to Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Hawaii, the continental U.S., and beyond. Alien anoles can have major impacts on the ecological communities that they invade, for instance leading to local extinction of arthropod taxa and displacing native anole species. It is therefore key to detect and report instances of introduction by these potentially aggressive invaders, as well as to document their geographic spread in colonized regions. In a recent paper, we report on the presence of Anolis porcatus, a species native from Cuba, in coastal southeastern Brazil, using DNA sequence data to support species identification and examine the geographic source of introduction.

Anolis porcatus collected in Brazil, and comparison with the native anole A. punctatus. A, male A. porcatus showing green coloration. B, male A. porcatus showing brown coloration. C, the pink dewlap of male A. porcatus. D, female A. porcatus. E, male A. punctatus, a native anole species. F, the yellow dewlap of male A. punctatus. Picture credits: A–D, Mauro Teixeira Jr.; E, Renato Recoder.

Perhaps embarrassingly, this study started with Facebook. On August 2015, Ricardo Samelo, an undergraduate Biology student at the Universidade Paulista in Santos, posted a few pictures of an unknown green lizard in the group ‘Herpetologia Brasileira.’ A heated debate about the animal’s identity took place, with people eventually agreeing on Anolis carolinensis. On my way to Brazil to join the Brazilian Congress of Herpetology, I contacted Ricardo (but only after properly hitting the ‘like’ button) and proposed to examine whether the exotic anole was established more broadly in the Baixada Santista region.

To our surprise, local residents knew the lizards well, with some people quite fond of the ‘lagartixas’ due to their pink dewlap displays. People could often tell when the anoles were first noticed in the vicinities – ‘six months’, ‘nine months’, ‘one year ago’ –, suggesting a rather recent presence. Guided by these informal reports, we sampled sites in the municipalities of Santos, São Vicente and Guarujá, where we found dozens of lizards occupying building walls, light posts, fences, debris, trees, shrubs, and lawn in residential yards, abandoned lots, and alongside streets and sewage canals. It was clear that the alien anoles are doing great in human-modified areas; the high density of individuals across multiple sites, as well as the presence of juveniles with various body sizes, seem to suggest a well-established reproductive population.

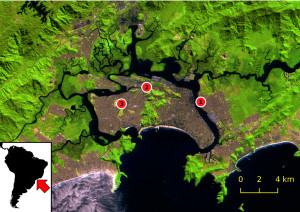

Sites in the Baixada Santista in southeastern coastal Brazil where introduced A. porcatus were detected. 1, Guarujá. 2, Santos. 3, São Vicente. Green indicates Atlantic Forest cover; gray indicates urban areas; black indicates water bodies.

By reading and bugging experienced anole researchers about the Anolis carolinensis species group, I learned about paraphyly among species, hybridization, and unclear species diagnosis based on external morphology. As a result, my PhD supervisor, Dr. Ana Carnaval, and I decided to recruit Leyla Hernandez, by the time an undergraduate student in the Carnaval Lab at the City University of New York, to help generate DNA sequences to clarify the species identity, and perhaps track the geographic source of introduction in Brazil. To our surprise, a phylogenetic analysis found Brazilian samples to nest within Anolis porcatus, a Cuban species that has also been introduced to Florida and the Dominican Republic. Brazilian A. porcatus clustered with samples from La Habana, Matanzas, and Pinar del Río, which may suggest a western Cuban source of colonization. Nevertheless, Brazilian specimens are also closely related to a sample from Coral Gables in Florida, which may suggest that the Brazilian population originated from lizards that are exotic elsewhere.

It is currently unclear whether A. porcatus will be able to expand into the surrounding coastal Atlantic Rainforest, or into more open natural settings such as shrublands in the Cerrado domain. It is also unknown whether this species will have negative impacts on the local ecological communities. In Brazil, introduced A. porcatus may potentially compete with other diurnal arboreal lizards, such as Enyalius, Polychrus, Urostrophus, and the native Anolis. Five native anoles inhabit the Atlantic Forest (for sure): A. fuscoauratus, A. nasofrontalis, A. ortonii, A. pseudotigrinus, and A. punctatus. While none of them is currently known to occur in sympatry with A. porcatus, the worryingly similar A. punctatus has been reported for a site in Bertioga located only 50 kilometers from the site in Guarujá where we found the exotic anoles.

It is currently unclear whether A. porcatus will be able to expand into the surrounding coastal Atlantic Rainforest, or into more open natural settings such as shrublands in the Cerrado domain. It is also unknown whether this species will have negative impacts on the local ecological communities. In Brazil, introduced A. porcatus may potentially compete with other diurnal arboreal lizards, such as Enyalius, Polychrus, Urostrophus, and the native Anolis. Five native anoles inhabit the Atlantic Forest (for sure): A. fuscoauratus, A. nasofrontalis, A. ortonii, A. pseudotigrinus, and A. punctatus. While none of them is currently known to occur in sympatry with A. porcatus, the worryingly similar A. punctatus has been reported for a site in Bertioga located only 50 kilometers from the site in Guarujá where we found the exotic anoles.

To properly evaluate the potentially invasive status of A. porcatus in Brazil, we hope to continue assessing the extent of its distribution and potential for future spread, as well as to gather data about whether and how A. porcatus will interact with the local species – especially native Brazilian anoles. This seemingly recent, currently expanding colonization also represents an exciting opportunity for comparisons with other instances of introduction of A. porcatus, as well as the closely-related A. carolinensis, based on ecological and phenotypic data.

Studying such mysterious alien anoles in Brazil was made much more tractable through advice from Jonathan Losos and Richard Glor. Thank you!

Source: http://www.anoleannals.org/2017/02/09/cuban-anolis-porcatus-introduced-to-brazil-perhaps-through-florida/