| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Gas Hydrate Breakdown Unlikely to Cause Massive Greenhouse Gas Release

The breakdown of methane hydrates due to warming climate is unlikely to lead to massive amounts of methane being released to the atmosphere, according to a recent interpretive review of scientific literature performed by the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Rochester.

Methane hydrate, which is also referred to as gas hydrate, is a naturally-occurring, ice-like form of methane and water that is stable within a narrow range of pressure and temperature conditions. These conditions are mostly found in undersea sediments at water depths greater than 1000 to 1650 ft and in and beneath permafrost (permanently frozen ground) at high latitudes.

Methane hydrates are distinct from conventional natural gas, shale gas, and coalbed methane reservoirs and are not currently exploited for energy production, either in the United States or the rest of the world.

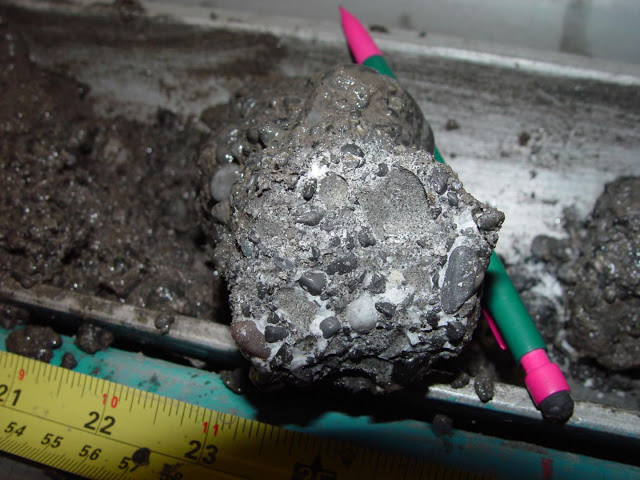

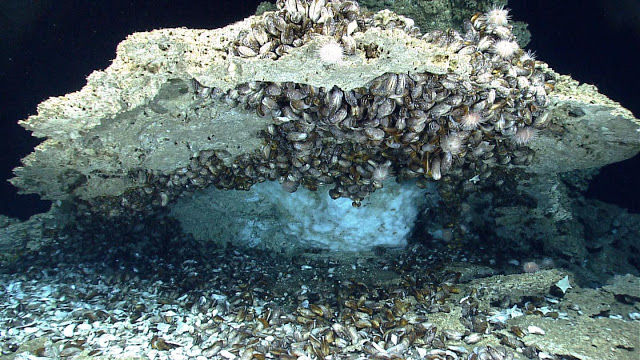

Gas hydrate (white, ice-like material) under authigenic carbonate rock that is encrusted with deep-sea chemosynthetic mussels and other organisms on the seafloor of the northern Gulf of Mexico at 966 m (~3170 ft) water depth. Although gas hydrate that forms on the seafloor is not an important component of the global gas hydrate inventory, deposits such as these demonstrate that methane and other gases cross the seafloor and enter the ocean.

Photograph was taken by the Deep Discoverer remotely operated vehicle in April 2014 and is courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Exploration and Research Program.

The new review concludes that current warming of ocean waters is likely causing gas hydrate deposits to break down at some locations. However, not only are the annual emissions of methane to the ocean from degrading gas hydrates far smaller than greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere from human activities, but most of the methane released by gas hydrates never reaches the atmosphere. Instead, the methane often remains in the undersea sediments, dissolves in the ocean, or is converted to carbon dioxide by microbes in the sediments or water column.

The review pays particular attention to gas hydrates beneath the Arctic Ocean, where some studies have observed elevated rates of methane transfer between the ocean and the atmosphere. As noted by the authors, the methane being emitted to the atmosphere in the Arctic Ocean has not been directly traced to the breakdown of gas hydrate in response to recent climate change, nor as a consequence of longer-term warming since the end of the last Ice Age.

Summary of the locations where gas hydrate occurs beneath the seafloor, in permafrost areas, and beneath some ice sheets, along with the processes (shown in red) that destroy methane (sinks) in the sediments, ocean, and atmosphere. The differently colored circles denote different sources of methane. Gas hydrates are likely breaking down now on shallow continental shelves in the Arctic Ocean and at the feather edge of gas hydrate stability on continental margins (1000-1650 feet).

Credit: Ruppel and Kessler (2017).

Professor Kessler explains that, “Even where we do see slightly elevated emissions of methane at the sea-air interface, our research shows that this methane is rarely attributable to gas hydrate degradation.”

The review summarizes how much gas hydrate exists and where it occurs; identifies the technical challenges associated with determining whether atmospheric methane originates with gas hydrate breakdown; and examines the assumptions of the Intergovernmental Panels on Climate Change, which have typically attributed a small amount of annual atmospheric methane emissions to gas hydrate sources.

The review also systematically evaluates different environments to assess the susceptibility of gas hydrates at each location to warming climate and addresses the potential environmental impact of an accidental gas release associated with a hypothetical well producing methane from gas hydrate deposits.

Virginia Burkett, USGS Associate Director for Climate and Land Use Change, noted, “This review paper provides a truly comprehensive synthesis of the knowledge on the interaction of gas hydrates and climate during the contemporary period. The authors’ sober, data-driven analyses and conclusions challenge the popular perception that warming climate will lead to a catastrophic release of methane to the atmosphere as a result of gas hydrate breakdown.”

Contacts and sources:

The paper, “The Interaction of Climate Change and Methane Hydrates,” by C. Ruppel and J. Kessler, is published in Reviews of Geophysics and is available here. The USGS and University of Rochester research that contributed to the review was largely supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

Source: http://www.ineffableisland.com/2017/02/gas-hydrate-breakdown-unlikely-to-cause.html