| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Insect Courtship Trapped in 100-Million-Year-Old Amber

Recently, Dr. Zheng Daran and Prof. Wang Bo from Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences described three male damselflies showing ancient courtship behaviour from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. These fossils were named Yijenplatycnemis huangi after Mr. Huang Yijen from Taiwan, for his generously donation of the type specimen.

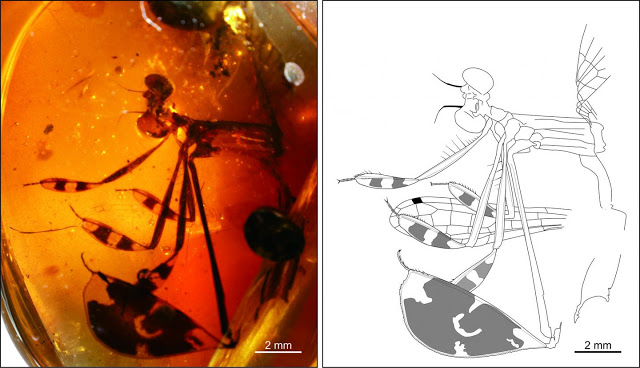

Photograph and line drawing of specimen Yijenplatycnemis huangi.

Image by Zheng Daran

Y. huangi has spectacular extremely expanded, pod-like tibiae, helping to fend off other suitors as well as attract mating females, increasing the chances of successful mating. The new findings provide suggestive evidence of damselfly courtship behaviour as far back as the dinosaur age.

Similarly, male East Asian Platycnemis species with expanded, feather-like tibiae well differentiated from the females, exhibit a strong sexual dimorphism. The males display their white legs in a fluttering flight in front of females before mating. By morphological inference, the six extremely expanded tibiae of Y. huangi could also have a signaling function for courtship displays. Platycypha has all six tibiae expanded, but all less so than Y. huangi in size. Platycnemis has more expanded mid and hind tibiae, but is still smaller than Y. huangi. These more expanded fossil tibiae suggest an extreme adaptation for courtship behaviour.

More importantly, unlike Platycypha and Platycnemis, the tibiae of Y. huangi are asymmetric and pod-shaped, especially the hind leg tibia with a semi-circular outline. This pod-like shape would make waving slower due to air resistance. Y. huangi waving its giant pod-like tibiae would make males more easily noticed and attract female attention, increasing mating opportunities and implying sexual selection.

Deflective eyespots in butterflies and fossil lacewings are smaller than deimatic ones and both are never on the legs, but dragonflies are predators with good eyesight, and the tiny ones in Y. huangi may have less to do with paralleling fossil lacewings in deflecting nearby predators and more to do with raising the interest of females (cf. peacock eyespots). That none of the pigmented tibiae in Y. huangi are damaged, however, suggests they did not precipitate an aggressive response.

This research was recently published in Scientific Reports, and supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the HKU Seed Funding Program for Basic Research.

Source: http://www.ineffableisland.com/2017/03/insect-courtship-trapped-in-100-million.html