| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Wicked Winds Would Destroy Earth, A Cosmic Rosetta Stone Found

X-ray satellites are monitoring the clashing winds of a colossal binary star system that could blow away our atmosphere if it were happening in our solar system.

Credit: NASA/C. Reed

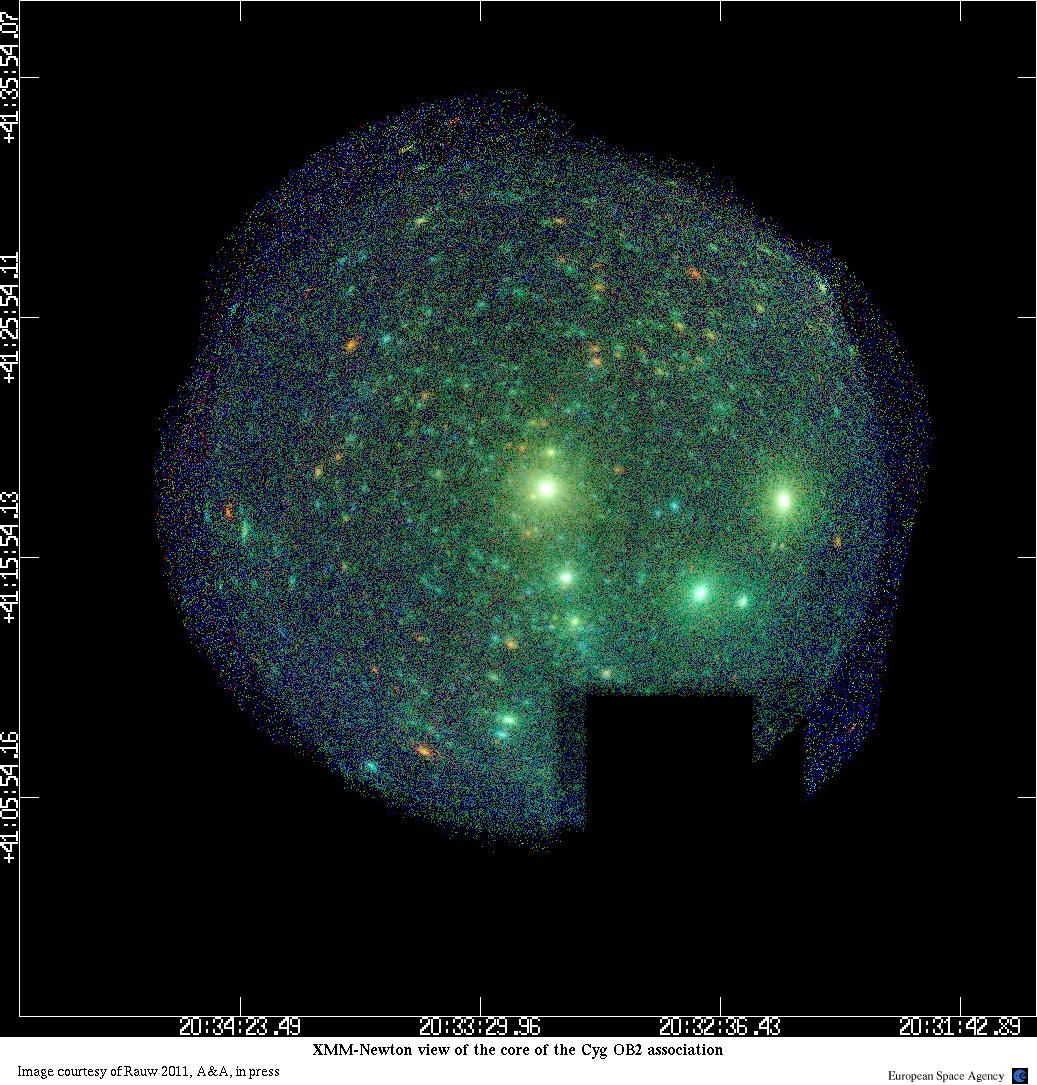

Credits: ESA/G. Rauw

Stellar winds, pushed away from a massive star’s surface by its intense light, can have a profound influence on their environment.

In some locations, they may trigger the collapse of surrounding clouds of gas and dust to form new stars.

Two sets of measurements taken 5.5 days apart near the time of periastron — one in late June by XMM-Newton and one in early July by Swift — show that the X-ray flux increased by four times when the stars were closest together. This is compelling evidence for the interaction of fierce stellar winds.

O-type stars are among the most massive and hottest known, pounding their surroundings with intense ultraviolet light and powerful outflows called stellar winds. NASA’s Swift and ESA’s XMM-Newton X-ray observatories took part in a 2011 campaign to monitor the interaction of two O stars bound together in the same binary system: Cygnus OB2 #9.

In others, they may blast the clouds away before they have the chance to get started.

Now, XMM-Newton and Swift have found a ‘Rosetta stone’ for such winds in a binary system known as Cyg OB2 #9, located in the Cygnus star-forming region, where the winds from two massive stars orbiting around each other collide at high speeds.

Cyg OB2 #9 remained a puzzle for many years. Its peculiar radio emission could only be explained if the object was not a single star but two, a hypothesis that was confirmed in 2008.

At the time of the discovery, however, there was no direct evidence for the winds from the two stars colliding, even though the X-ray signature of such a phenomenon was expected.

This signature could only be found by tracking the stars as they neared the closest point on their 2.4-year orbit around each other, an opportunity that presented itself between June and July 2011.

As the space telescopes looked on, the fierce stellar winds slammed together at speeds of several million kilometres per hour, generating hot plasma at a million degrees which then shone brightly in X-rays.

Credit: Univ. of Liège/E. R. Parkin and E. Gosset

The telescopes recorded a four-fold increase in energy compared with the normal X-ray emission seen when the stars were further apart on their elliptical orbit.

“This is the first time that we have found clear evidence for colliding winds in this system,” says Yael Nazé of the Université de Liège, Belgium, and lead author of the paper describing the results reported in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

“We only have a few other examples of winds in binary systems crashing together, but this one example can really be considered an archetype for this phenomenon.”

Unlike the handful of other colliding wind systems, the style of the collision in Cyg OB2 #9 remains the same throughout the stars’ orbit, despite the increase in intensity as the two winds meet.

“In other examples the collision is turbulent; the winds of one star might crash onto the other when they are at their closest, causing a sudden drop in X-ray emission,” says Dr Nazé.

“But in the Cyg OB2 #9 system there is no such observation, so we can consider it the first ‘simple’ example that has been discovered – that really is the key to developing better models to help understand the characteristics of these powerful stellar winds. ”

Credit: ESA/Gregor Rauw, Univ. of Liège

“This particular binary system represents an important stepping stone in our understanding of stellar wind collisions and their associated emissions, and could only be achieved by tracking the two stars orbiting around each other with X-ray telescopes,” adds ESA’s XMM-Newton project scientist Norbert Schartel.

To maximize their chances of catching X-rays from colliding winds, the researchers needed to monitor the system as the stars raced toward their closest approach, or periastron. The first opportunity arose in 2011.

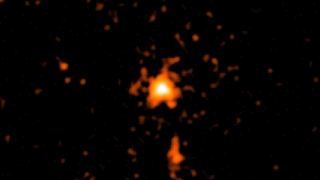

NASA’s Swift made five sets of X-ray observations during the 10 months around the date of periastron, and XMM-Newton carried out one high-resolution observation near the predicted time of closest approach. The new data indicate that Cygnus OB2 #9 is a massive binary with components of similar mass and luminosity following long, highly eccentric orbits. The most massive star in the system has about 50 times the sun’s mass, and its companion is slightly smaller, with about 45 solar masses. At periastron, these stellar titans are separated by less than three times Earth’s average distance from the sun.

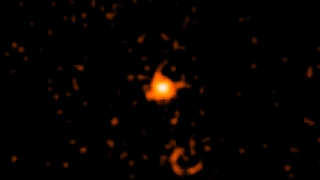

Swift X-ray image of Cyg OB2 #9 from April 4, 2011.

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

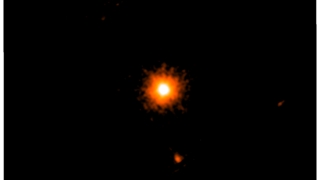

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

Credit: NASA/GSFC/S. Immler

Class O stars are very hot and extremely luminous, being bluish in color; in fact, most of their output is in the ultraviolet range. These are the rarest of all main-sequence stars. About 1 in 3,000,000 (0.00003%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are Class O stars.[nb 1][12] Some of the most massive stars lie within this spectral class. Type-O stars are so hot as to have complicated surroundings which make measurement of their spectra difficult.

O-stars shine with a power over a million times our Sun’s output. These stars have dominant lines of absorption and sometimes emission for He II lines, prominent ionized (Si IV, O III, N III, and C III) and neutral helium lines, strengthening from O5 to O9, and prominent hydrogen Balmer lines, although not as strong as in later types. Because they are so massive, class O stars have very hot cores, thus burn through their hydrogen fuel very quickly, and so are the first stars to leave the main sequence. Recent observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope indicate that planetary formation does not occur around other stars in the vicinity of an O class star due to the photoevaporation effect

Class B stars are very luminous and blue. Their spectra have neutral helium, which are most prominent at the B2 subclass, and moderate hydrogen lines. Ionized metal lines include Mg II and Si II. As O and B stars are so powerful, they only live for a relatively short time, and thus they do not stray far from the area in which they were formed.

These stars tend to be found in their originating OB associations, which are associated with giant molecular clouds. The Orion OB1 association occupies a large portion of a spiral arm of our galaxy and contains many of the brighter stars of the constellation Orion. About 1 in 800 (0.125%) of the main-sequence stars in the solar neighborhood are Class B stars

Credit: ESA/Hubble, NASA and D. A Gouliermis. Acknowledgement: Flickr user Eedresha Sturdivant

The stellar grouping is known to stargazers as NGC 2040 or LH 88. It is essentially a very loose star cluster whose stars have a common origin and are drifting together through space. There are three different types of stellar associations defined by their stellar properties. NGC 2040 is an OB association, a grouping that usually contains 10–100 stars of type O and B — these are high-mass stars that have short but brilliant lives.

It is thought that most of the stars in the Milky Way were born in OB associations.

Contacts and sources:

Full bibliographic information“The 2.35 years itch of Cyg OB2 #9 I. Optical and X-ray monitoring” by Y. Nazé et al., is accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The only corrosive wind presently harming the Earth’s atmosphere being generated in Washington by blow-hard politicians who think they are greater than God.

LoL! You Sir are Correct!!

It ain’t Nibiru. It’s just corrosive winds that “could” blow away our atmosphere if our sun were, by chance, in a binary star system. Very clever backdoor.

NASA wouldn’t tell us anything that might cause all us chilluns to lose any sleep now, would they ? Heaven forbid. They would have to call FEMA to issue everyone a cosmic windbreaker and a can of oxygen.

Heaven forbid. They would have to call FEMA to issue everyone a cosmic windbreaker and a can of oxygen.

~*~