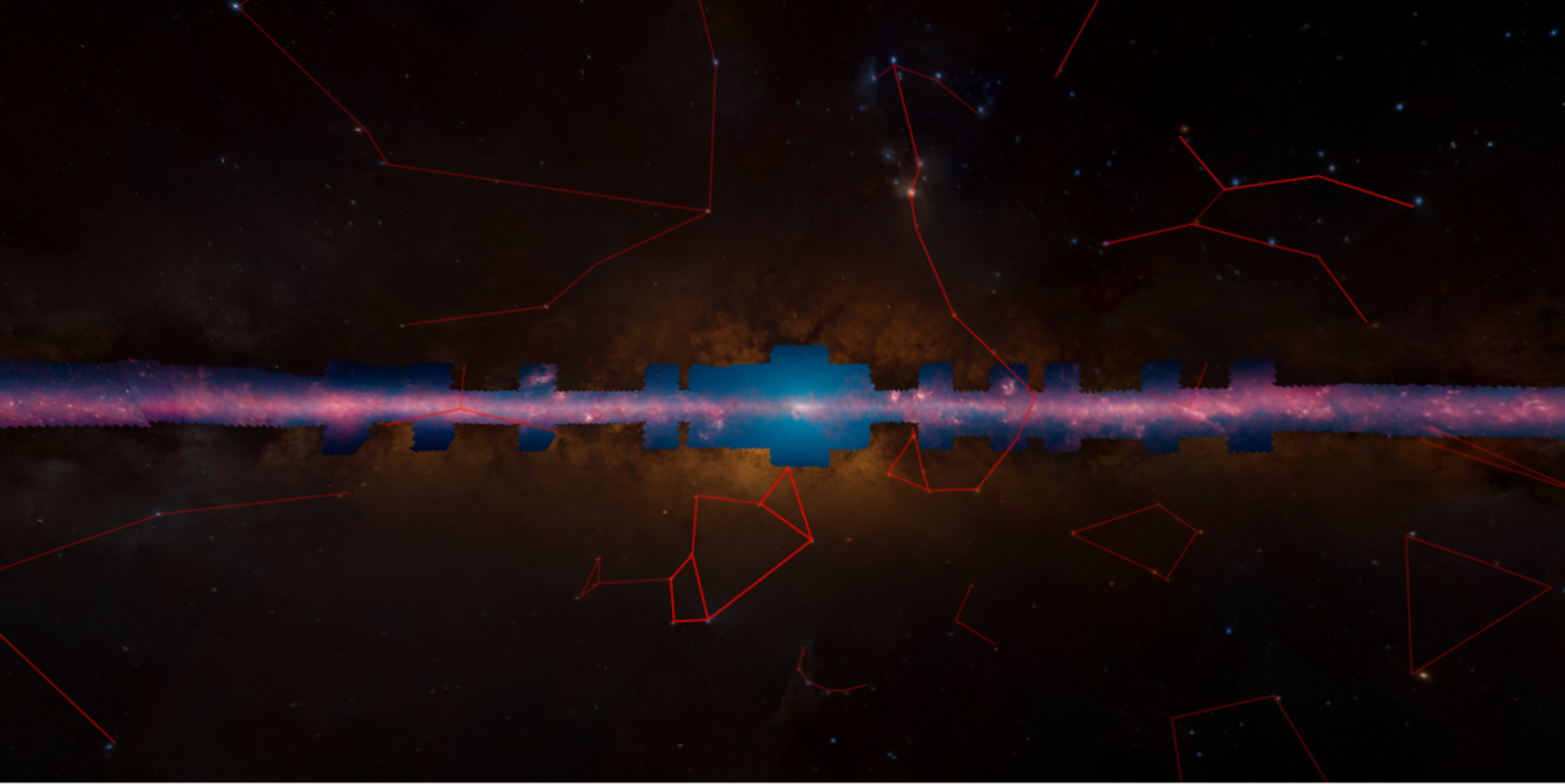

The galactic portrait provides an unprecedented look at the plane of our galaxy, using the infrared imagers aboard Spitzer to cut through the interstellar dust that obscures the view in visible light.

More than 200 million images like this one have been stitched together by Wisconsin astronomers to make a 360-degree portrait of the plane of our galaxy, the Milky Way. In this image, the billowing pink clouds are massive stellar nurseries. The stringy green filaments are the blown out remnants of a star that exploded in a supernova.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Wisconsin-Madison

“For the first time, we can actually measure the large-scale structure of the galaxy using stars rather than gas,” explains Edward Churchwell, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of astronomy whose group compiled the new picture, which looks at a thin slice of the galactic plane. “We’ve established beyond the shadow of a doubt that our galaxy has a large bar structure that extends halfway out to the sun’s orbit. We know more about where the Milky Way’s spiral arms are.”

Lofted into space in 2003, the Spitzer Space Telescope has far exceeded its planned two-and-a-half-year lifespan. Although limited by the depletion of the liquid helium used to cool its cameras, the telescope remains in heliocentric orbit, gathering a trove of astrophysical data that promises to occupy a new generation of astronomers.

In addition to providing new revelations about galactic structure, the telescope and the images processed by the Wisconsin team have made possible the addition of more than 200 million new objects to the catalog of the Milky Way.

“This gives us some idea about the general distribution of stars in our galaxy, and stars, of course, make up a major component of the baryonic mass of the Milky Way,” notes Churchwell, whose group has been collecting and analyzing Spitzer data for more than a decade in a project known as GLIMPSE (Galactic Legacy Infrared Midplane Survey Extraordinaire). “That’s where the ballgame is.”

The new infrared picture, known as GLIMPSE360, was compiled by a team led by UW-Madison astronomer Barb Whitney. It is interactive and zoomable, giving users the ability to look through the plane of the galaxy and zero in on a variety of objects, including nebulae, bubbles, jets, bow shocks, the center of the galaxy and other exotic phenomena. The image is being shown for the first time this morning on a large visualization wall installed by Microsoft at the TED conference.

For Interactive view: http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/glimpse360/wwt

The survey conducted by the Wisconsin group has also helped astronomers understand the distribution of the Milky Way’s stellar nurseries, regions where massive stars and proto-stars are churned out.

“We can see every star-forming region in the plane of the galaxy,” says Robert Benjamin, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater and a member of the GLIMPSE team.

“This gives us some idea of the metabolic rate of our galaxy,” explains Whitney. “It tells us how many stars are forming each year.”

Churchwell notes, too, that while Spitzer is helping astronomers resolve some of the mysteries of the Milky Way, it is adding new cosmological puzzles for scientists to ponder. For example, the infrared data gathered by the GLIMPSE team has revealed that interstellar space is filled with diffuse polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon gas.

“These are hydrocarbons — very complicated, very heavy molecules with fifty or more carbon atoms,” Churchwell says. “They are brightest around regions of star formation but detectable throughout the disk of the Milky Way. They’re floating out in the middle of interstellar space where they have no business being. It raises the question of how they were formed. It also tells us carbon may be more abundant than we thought.”

The new GLIMPSE composite image will be made widely available to astronomers and planetaria. The data is also the basis for a “citizen science” project, known as the Milky Way Project, where anyone can help scour GLIMPSE images to help identify and map the objects that populate our galaxy.

This video shows a continually looping view of the Spitzer Space Telescope’s new infrared view of our Milky Way Galaxy. The 360-degree mosaic comes primarily from the GLIMPSE360 project, which stands for Galactic Legacy Mid-Plane Survey Extraordinaire. It consists of more than 2 million snapshots taken in infrared light over ten years, beginning in 2003 when Spitzer launched.

The radar view to the bottom right of the screen shows the direction currently being displayed in the main image, centered on our position in the suburbs of the Milky Way.

This infrared image reveals much more of the galaxy than can be seen in visible-light views. Whereas visible light is blocked by dust, infrared light from stars and other objects can travel through dust to reach Spitzer’s detectors. For instance, when looking up at our night skies, we see stars that are an average of 1,000 light-years away; the rest are hidden. In Spitzer’s mosaic, light from stars throughout the galaxy — which stretches 100,000 light-years across — shines through. This picture covers only about three percent of the sky, but includes more than half of the galaxy’s stars and the majority of its star formation activity.

The red color shows dusty areas of star formation. Throughout the galaxy, tendrils, bubbles and sculpted dust structures are apparent. These are the result of massive stars blasting out winds and radiation. Stellar clusters deeply embedded in gas and dust, green jets and other features related to the formation of young stars can also be seen for the first time. Looking towards the galactic center, the blue haze is made up of starlight — the region is too far away for us to pick out individual stars, but they contribute to the glow. Dark filaments that show up in stark contrast to the bright background are areas of thick, cold dust that not even infrared light can penetrate.

The GLIMPSE360 map will guide astronomers for generations, helping them to further chart the unexplored territories of our own Milky Way.

The data from the survey, Churchwell argues, will keep astronomers busy for many years: “It’s still up there. It’s still taking data. It’s done what we wanted it to do, which is to provide a legacy of data for the astronomical community.”

No one can see the video because it’s private???? WTF!!!!!!!!!!!

Agree, WTF? This is happening a lot on BIN

Was able to watch video w/ out any problems. Was ok

No problem with the video here as well……