| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Ground-Based Detection Of Super-Earth Transit Paves Way To Remote Sensing Of Exoplanets

For the first time, a team of astronomers – including York University Professor Ray Jayawardhana – have measured the passing of a super-Earth in front of a bright, nearby Sun-like star using a ground-based telescope.

The international research team used the 2.5-meter Nordic Optical Telescope on the island of La Palma, Spain – a moderate-sized facility by today’s standards – to make the detection. Previous observations of this planet transit had to rely on space-borne telescopes.

During its transit, the planet crosses its host star, 55 Cancri, located just 40 light-years away from us and visible to the naked eye, blocking a tiny fraction of the starlight, dimming the star by 1/2000th (or 0.05%) for almost two hours.

“Our observations show that we can detect the transits of small planets around Sun-like stars using ground-based telescopes,” says Dr. Ernst de Mooij, of Queen’s University Belfast, UK, the study’s lead author. “This is especially important because upcoming space missions such as TESS and PLATO should find many small planets around bright stars.”

TESS is a NASA mission scheduled for launch in 2017, while PLATO is to be launched in 2024 by the European Space Agency; both will search for transiting terrestrial planets around nearby bright stars.

“It’s remarkable what we can do by pushing the limits of existing telescopes and instruments, despite the complications posed by the Earth’s own turbulent atmosphere,” says Jayawardhana, the study’s co-author and de Mooij’s former postdoctoral supervisor. “Observations like these are paving the way as we strive towards searching for signs of life on alien planets from afar. Remote sensing across tens of light-years isn’t easy, but it can be done with the right technique and a bit of ingenuity.”

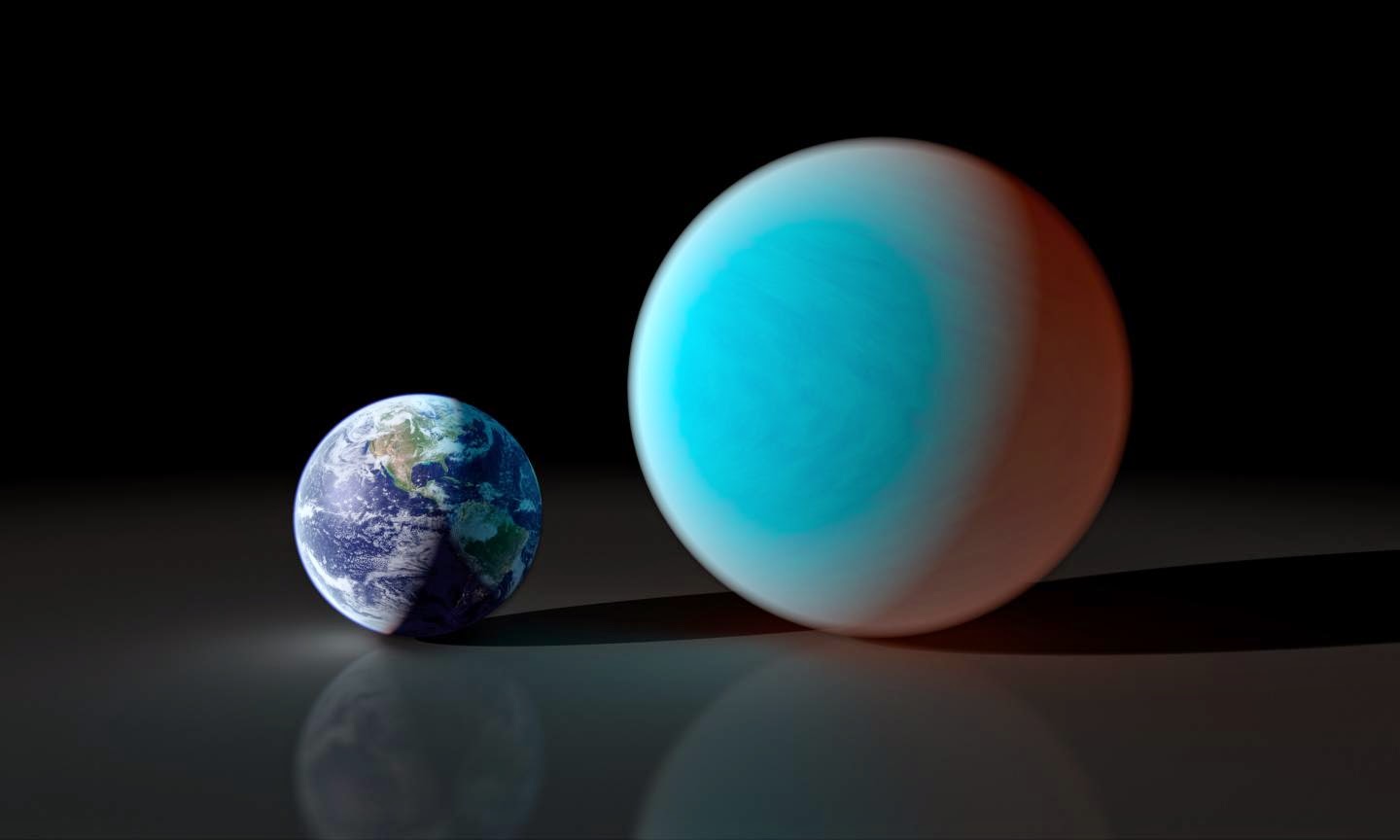

The planet 55 Cancri e is about twice as big and eight times as massive as the Earth. With a period of 18 hours, it is the innermost of five planets in the system. Because of its proximity to the host star, the planet’s dayside temperature reaches over 1700 Celsius – hot enough to melt metal – with conditions quite inhospitable to life. Initially identified a decade ago through radial velocity measurements, it was later confirmed through transit observations with MOST and Spitzer space telescopes.

Next, the team plans to search for steam (water) in the planet’s atmosphere.

The research team also includes Mercedes Lopez-Morales of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, as well as Raine Karjalainen and Marie Hrudkova of the Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes. Their findings will appear in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Source: