| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

‘Perfect Storm’ Quenching Star Formation Around A Supermassive Black Hole

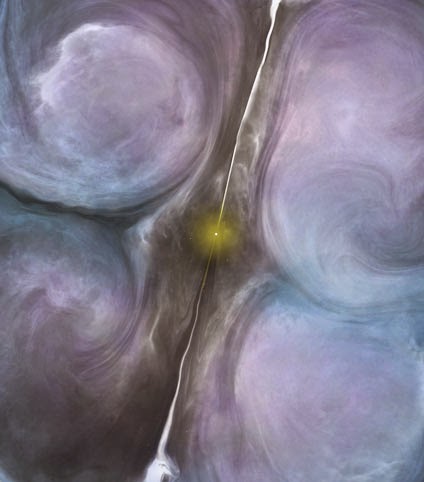

Artist impression of the central region of NGC 1266. The jets from the central black hole are creating turbulence in the surrounding molecular gas, suppressing star formation in an otherwise ideal environment to form new stars.

This turbulence is stirred up by jets from the galaxy’s central black hole slamming into an incredibly dense envelope of gas. This dense region, which may be the result of a recent merger with another smaller galaxy, blocks nearly 98 percent of material propelled by the jets from escaping the galactic center.

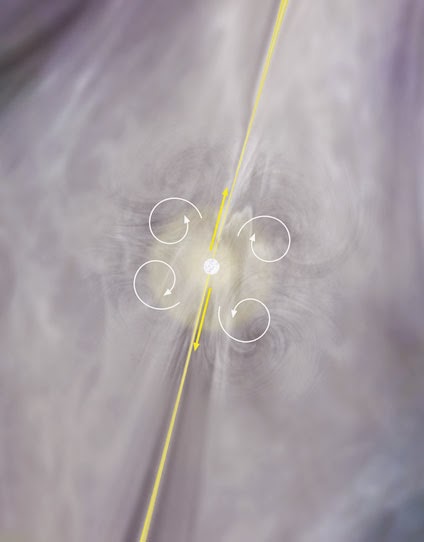

Artist illustration of the central region of NGC 1266 near its central black hole with jet and gas motions indicated (yellow and white arrows, respectively). The large-scale gas motions induce turbulence on smaller scales, preventing star formation.

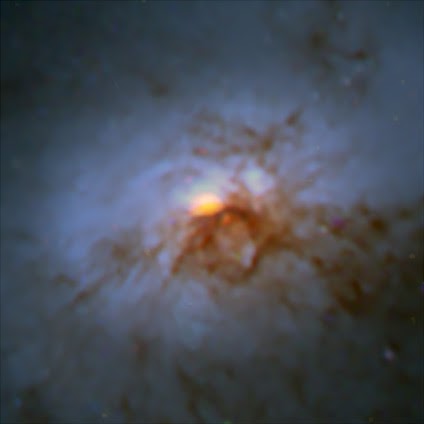

A combined Hubble Space Telescope / ALMA image of NGC 1266. The ALMA data (orange) are shown in the central region.

“Another way of looking at it is that the jets are injecting turbulence into the gas, preventing it from settling down, collapsing, and forming stars,” said National Radio Astronomy Observatory astronomer and co-author Mark Lacy.

The region observed by ALMA contains about 400 million times the mass of our Sun in star-forming gas, which is 100 times more than is found in giant star-forming molecular clouds in our own Milky Way. Normally, gas this concentrated should be producing stars at a rate at least 50 times faster than the astronomers observe in this galaxy.

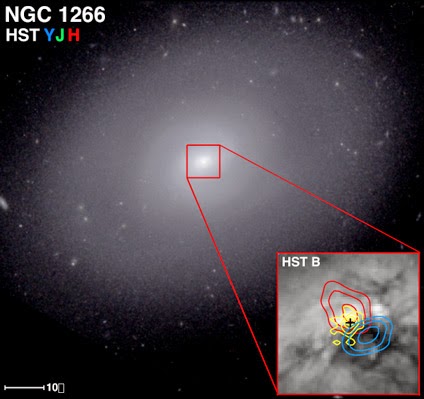

A combined Hubble/CARMA image of NGC 1266. The zoom-in section shows the molecular gas being propelled by the black hole’s jets (red and blue), the central CARMA data (yellow) indicate the dense molecular gas.

Previously, astronomers believed that only extremely powerful quasars and radio galaxies contained black holes that were powerful enough to serve as a star-forming “on/off” switch.

“The usual assumption in the past has been that the jets needed to be powerful enough to eject the gas from the galaxy completely in order to be effective at stopping start formation,” said Lacy.

To make this discovery, the astronomers first pinpointed the location of the far-infrared light being emitted by the galaxy. Normally, this light is associated with star formation and enables astronomers to detect regions where new stars are forming. In the case of NGC 1266, however, this light was coming from an extremely confined region at the center of the galaxy. “This very small area was almost too small for the infrared light to be coming from star formation,” noted Alatalo.

With ALMA’s exquisite sensitivity and resolution, and along with observations from CARMA (the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy), the astronomers were then able to trace the location of the very dense molecular gas at the galactic center. They found that the gas is surrounding this compact source of far-infrared light.

Under normal conditions, gas this dense would be forming stars at a very high rate. The dust embedded within this gas would then be heated by young stars and seen as a bright and extended source of infrared light. The small size and faintness of the infrared source in this galaxy suggests that NGC 1266 is instead choking on its own fuel, seemingly in defiance of the rules of star formation.

The astronomers also speculate that there is a feedback mechanism at work in this region. Eventually, the black hole will calm down and the turbulence will subside so star formation can begin anew. With this renewed star formation, however, comes greater motion in the dense gas, which then falls in on the black hole and reestablishes the jets, shutting down star formation once again.

NGC 1266 is located approximately 100 million light-years away in the constellation Eridanus. Leticular galaxies are spiral galaxies, like our own Milky Way, but they have little interstellar gas available to form new stars.

Contacts and sources:

Charles Blue

National Radio Astronomy Observatory

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of Europe, North America and East Asia in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded in Europe by the European Organization for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), in North America by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC) and in East Asia by the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led on behalf of Europe by ESO, on behalf of North America by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), which is managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI) and on behalf of East Asia by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ). The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

Source: