| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Why the Sun’s Atmosphere Is Hotter Than Its Surface

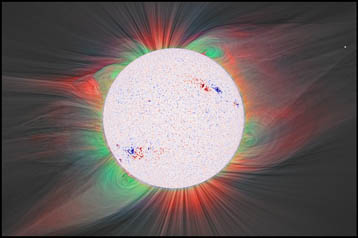

How can the temperature of the Sun’s atmosphere be as high as 1 million degrees Celsius when its surface temperature is only around 6000°C? By simulating the evolution of part of the Sun’s interior and exterior, researchers from the Centre de Physique Théorique (CNRS/École polytechnique) and the Laboratoire Astrophysique, Interprétation – Modélisation (CNRS/CEA/Université Paris Diderot) have identified the mechanisms that provide sufficient energy to heat the solar atmosphere.

Credit: © Tahar Amari / Centre de Physique Théorique and S. Habbal / M. Druckmüller.

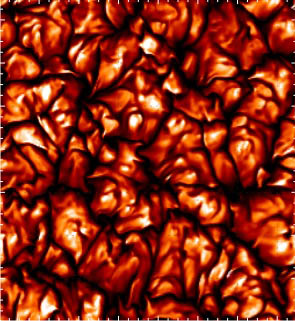

Using powerful numerical models run on computers at the Centre de Physique Théorique (CNRS/École Polytechnique) and GENCI at IDRIS-CNRS, the team performed a simulation for several hours, based on a model made up of several layers, one inside the Sun and the others in its atmosphere. The researchers observed that the thin layer under the Sun’s surface actually behaves rather like a shallow pan containing boiling plasma[2], heated from below and forming ‘bubbles’ associated with granules.

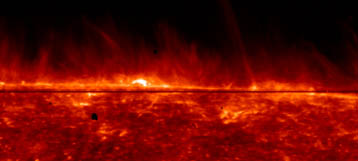

The Sun’s surface according to data from NASA’s IRIS mission, showing the dynamic structure of the heated atmosphere in the background.

The scientists also discovered that a structure resembling a mangrove forest appears around the solar mesospots: tangled ‘chromospheric roots’ dive into the spaces between the granules, surrounding ‘magnetic tree trunks’ that rise up towards the corona and are associated with the larger-scale magnetic field.

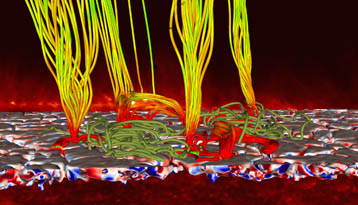

Model of the solar atmosphere at high-resolution, showing the formation of intense electric currents rising up like flames.

The researchers’ calculations show that, in the chromosphere, heating of the atmosphere results from multiple micro-eruptions in the mangrove roots that carry intense electric current, in pace with the ‘bubbles’ from the boiling plasma. They also discovered that larger but less numerous eruptive events take place in the neighborhood of the mesospots, although these are not able to heat the upper corona on a larger scale.

This eruptive process generates ‘magnetic’ waves along the tree trunks, rather like sound traveling along a plucked string. These waves then transport energy to the upper corona, which is heated by their progressive dissipation.

The researchers found that the energy fluxes of their mechanisms match those required by all studies to maintain the temperature of the plasma in the solar atmosphere, namely 4 500 W/m2 in the chromosphere and 300 W/m2 in the corona.

[1] The magnetic field lines are structured like roots and branches.

2 Plasma, often called the fourth state of matter, here represents an electrically conducting fluid.

3 Spicule: a thin jet of matter that emerges from the chromosphere and enters the corona.

Contacts and sources:

CNRS (Délégation Paris Michel-Ange)

Source:

how do you know that have you been there

have you been there

2 buttons Real or Fake News

you don’t need to leave a message