| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Hubble Reveals Diversity of Exoplanet Atmospheres; Study Solves Missing Water Mystery

To date, astronomers have discovered nearly 2000 planets orbiting other stars. Some of these planets are known as hot Jupiters — hot, gaseous planets with characteristics similar to those of Jupiter. They orbit very close to their stars, making their surface hot, and the planets tricky to study in detail without being overwhelmed by bright starlight.

Due to this difficulty, Hubble has only explored a handful of hot Jupiters in the past, across a limited wavelength range. These initial studies have found several planets to hold less water than expected (opo1436a, opo1354a).

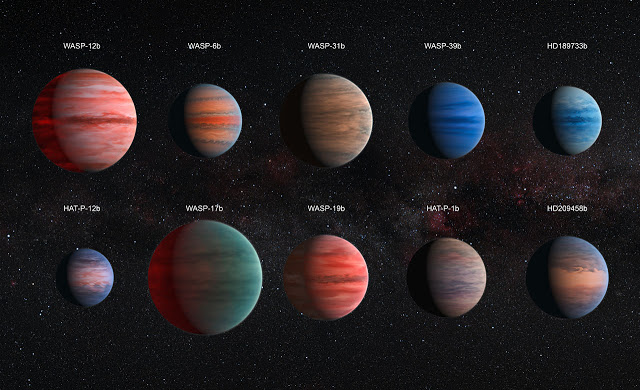

This image shows an artist’s impression of the ten hot Jupiter exoplanets studied by David Sing and his colleagues. The images are to scale with each other. HAT-P-12b, the smallest of them, is approximately the size of Jupiter, while WASP-17b, the largest planet in the sample, is almost twice the size. The planets are also depicted with a variety of different cloud properties. There is almost no information about the colours of the planets available, with the exception of HD 189733b, which became known as the blue planet (heic1312).

The hottest planets within the sample are portrayed with a glowing night side. This effect is strongest on WASP-12b, the hottest exoplanet in the sample, but also visible on WASP-19b and WASP-17b. It is also known that several of the planets exhibit strong Rayleigh scattering. This effect causes the blue hue of the daytime sky and the reddening of the Sun at sunset on Earth. It is also visible as a blue edge on the planets WASP-6b, HD 189733b, HAT-P-12b, and HD 209458b.

The wind patterns shown on these ten planets, which resemble the visible structures on Jupiter, are based on theoretical models

The team used multiple observations from both the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Using the power of both telescopes allowed the team to study the planets, which are of various masses, sizes, and temperatures, across an unprecedented range of wavelengths [2].

“I’m really excited to finally ‘see’ this wide group of planets together, as this is the first time we’ve had sufficient wavelength coverage to be able to compare multiple features from one planet to another,” says David Sing of the University of Exeter, UK, lead author of the new paper. “We found the planetary atmospheres to be much more diverse than we expected.”

All of the planets have a favourable orbit that brings them between their parent star and Earth. As the exoplanet passes in front of its host star, as seen from Earth, some of this starlight travels through the planet’s outer atmosphere. “The atmosphere leaves its unique fingerprint on the starlight, which we can study when the light reaches us,” explains co-author Hannah Wakeford, now at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA.

These fingerprints allowed the team to extract the signatures from various elements and molecules — including water — and to distinguish between cloudy and cloud-free exoplanets, a property that could explain the missing water mystery.

The team’s models revealed that, while apparently cloud-free exoplanets showed strong signs of water, the atmospheres of those hot Jupiters with faint water signals also contained clouds and haze — both of which are known to hide water from view. Mystery solved!

“The alternative to this is that planets form in an environment deprived of water — but this would require us to completely rethink our current theories of how planets are born,” explained co-author Jonathan Fortney of the University of California, Santa Cruz, USA. “Our results have ruled out the dry scenario, and strongly suggest that it’s simply clouds hiding the water from prying eyes.”

The study of exoplanetary atmospheres is currently in its infancy, with only a handful of observations taken so far. Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, will open a new infrared window on the study of exoplanets and their atmospheres.

Notes

[1] To date, studies of exoplanet atmospheres have been dominated by a small number of well-studied planets. The team used Hubble and Spitzer observations of two such planets, HD 209458b (heic0303, opo0707b) and HD 189733b (heic1312, heic0720a), and used Hubble to observe eight other exoplanets — WASP-6b, WASP-12b, WASP-17b, WASP-19b, WASP-31b, WASP-39b, HAT-P-1b, HAT-P-12b. These planets have a broad range of physical parameters.

[2] The observations spanned from the ultraviolet (0.3 μm) to the mid-infrared (4.5 μm).

Contacts and sources:

David Sing, University of Exeter

Hannah Wakeford, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Jonathan Fortney, University of California Santa Cruz

Mathias Jäger, ESA/Hubble, Public Information Officer

Source: