| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

How Giant Planets Form

Young giant planets are born from gas and dust. Researchers of ETH Zürich and the University of Zurich (UZH) simulated different scenarios relying on the computing power of the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) to find out how they exactly form and evolve.

Astronomers set up two theories explaining how gaseous giant planets like Jupiter or Saturn could be born. A bottom-up formation mechanism states that first, a solid core is aggregated of roughly ten times the size of the Earth. “Then, this core is massive enough to attract a significant amount of gas and keep it,” explains Judit Szulágyi, post-doctoral fellow at the ETH Zürich and member of the Swiss NCCR PlanetS.

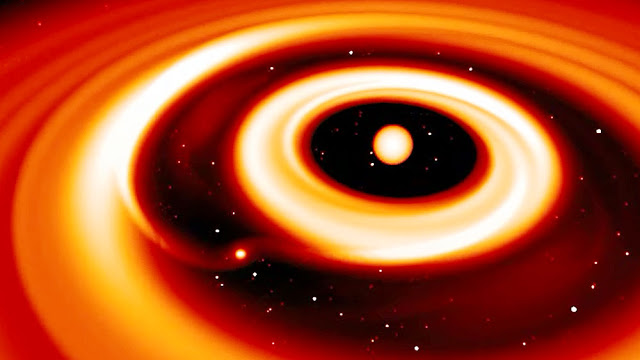

This image shows a virtual fly-by in the vicinity of a Jupiter-sized forming giant planet.

Image: Frederic Masset, ETH Zürich / CSCS

To find out which mechanism actually takes place in the Universe, Judit Szulágyi and Lucio Mayer, Professor at the Center for Theoretical Astrophysics and Cosmology at UZH, simulated the scenarios on Piz Daint supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) in Lugano. «We pushed our simulations to the limits in terms of the complexity of the physics added to the models,» explains Judit Szulágyi: “And we achieved higher resolution than anybody before.”

In their studies published in the “Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society” the researchers found a big difference between the two formation mechanisms: In the disk instability scenario the gas in the planet’s vicinity remained very cold, around 50 Kelvins, whereas in the core accretion case the circumplanetary disk was heated to several hundreds of Kelvins.

This huge temperature difference is easily observable. “When astronomers look into new forming planetary systems, just measuring the temperatures in the planet’s vicinity will be enough to tell which formation mechanism built the given planet,” explains Judit Szulágyi.

In a second study, Judit Szulágyi collaborated with Christoph Mordasini (University of Berne).

Contacts and sources:

Barbara Vonarburg

Source: