| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

First Big-Picture Look at Meteorites from Before Giant Space Collision 466 Million Years Ago

Four hundred and sixty-six million years ago, there was a giant collision in outer space. Something hit an asteroid and broke it apart, sending chunks of rock falling to Earth as meteorites since before the time of the dinosaurs. But what kinds of meteorites were making their way to Earth before that collision?

Researchers have discovered minerals from 43 meteorites that landed on Earth 470 million years ago. More than half of the mineral grains are from meteorites completely unknown or very rare in today’s meteorite flow. These findings mean that we will probably need to revise our current understanding of the history and development of the solar system.

The discovery confirms the hypothesis presented this summer when geology professor Birger Schmitz at Lund University in Sweden revealed that he had found what he referred to as an “extinct meteorite” – a meteorite dinosaur.

This is an artist’s rendering of the space collision 466 million years ago that gave rise to many of the meteorites falling today.

Image credit: © Don Davis, Southwest Research Institute.

“Looking at the kinds of meteorites that have fallen to Earth in the last hundred million years doesn’t give you a full picture,” explains Heck. “It would be like looking outside on a snowy winter day and concluding that every day is snowy, even though it’s not snowy in the summer.”

Credit; LundUniversity

“We knew almost nothing about the meteorite flux to Earth in geological deep time before this study,” says coauthor Birger Schmitz of Sweden’s Lund University. “The conventional view is that the solar system has been very stable over the past 500 million years. So it is quite surprising that the meteorite flux at 467 million years ago was so different from the present.”

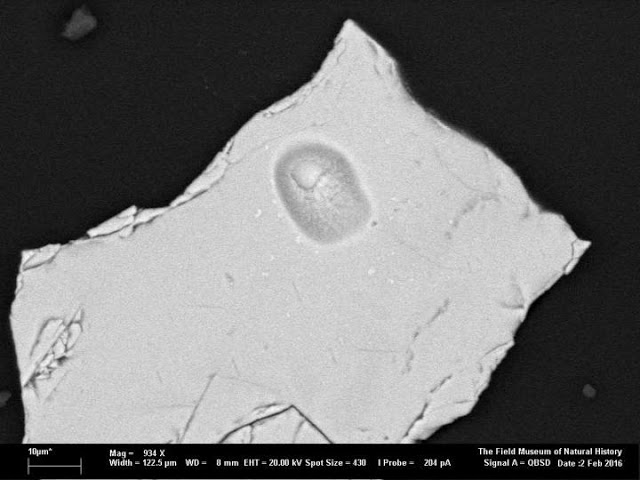

This is an electron microscope image of a polished cross section of chrome spinel from a fossil micrometeorite that scientists believe comes from the asteroid 4 Vesta.

“Chrome-spinels, crystals that contain the mineral chromite, remain unchanged even after hundreds of millions of years,” explains Heck. “Since they were unaltered by time, we could use these spinels to see what the original parent body that produced the micrometeorites was made of.”

Analysis of the chemical makeup of the spinels showed that the meteorites and micrometeorites that fell earlier than 466 million years ago are different from the ones that have fallen since. A full 34 percent of the pre-collision meteorites belong to a meteorite type called primitive achondrites; today, only 0.45 percent of the meteorites that land on Earth are this type. Other ancient micrometeorites sampled turned out to be relics from Vesta, the brightest asteroid visible from Earth, which underwent its own collision event over a billion years ago.

This is co-author Fredrik Terfelt of Lund University collecting rocks containing 467-million-year-old micrometeorites at Lynna River in Russia.

Photo Credit: © Birger Schmitz, Lund University.

“Knowing more about the different kinds of meteorites that have fallen over time gives us a better understanding of how the Asteroid Belt evolved and how different collisions happened,” says Heck. “Ultimately, we want to study more windows in time, not just the area before and after this collision during the Ordovician period, to deepen our knowledge of how different bodies in Solar System formed and interact with each other.”

The meteorite was given the name Österplana 065 and was discovered in a quarry outside Lidköping in Sweden. The term ‘extinct’ was used because of its unusual composition, different from all known groups of meteorites, and because it originated from a celestial body that was destroyed in ancient times.

The discovery led to the hypothesis that the flow of meteorites may have been completely different 470 million years ago compared to today, as meteorites with such a composition no longer fall on Earth.

“The new results confirm the hypothesis. Based on 43 micrometeorites, which are as old as Österplana 065, our new study shows that back then the flow was actually dramatically different. So far we have always assumed that the solar system is stable, and have therefore expected that the same type of meteorites have fallen on Earth throughout the history of the solar system, but we have now realised that this is not the case”, says Birger Schmitz.

Birger Schmitz conducted the study together with his colleagues at Lund University, the University of Chicago, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The result was unexpected. Birger Schmitz is convinced that something so far unknown but of fundamental importance in the history of the solar system occurred nearly 500 million years ago.

He also emphasises that the new study shows that it is possible to make highly detailed reconstructions of the changes that have occurred in the solar system.

“We can now recreate late history of not only the Earth but of the entire solar system. The scientific value of this new report is greater than the one last summer”, says Birger Schmitz.

This study was completed by researchers from The Field Museum, Sweden’s Lund University, Colorado’s Southwest Research Institute, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Russia’s Kazan Federal University.

Kate Golembiewski, Field Museum

Citation: Rare meteorites common in the Ordovician period. Authors: Philipp R. Heck, Birger Schmitz, William F. Bottke, Surya S. Rout, Noriko T. Kita, Anders Cronholm, Céline Defouilloy, Andrei Dronov & Fredrik Terfelt Nature Astronomy 1, Article number: 0035 (2017) doi:10.1038/s41550-016-0035 http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41550-016-0035

Source: