| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Tax Evaders Prefer Institutional Punishment

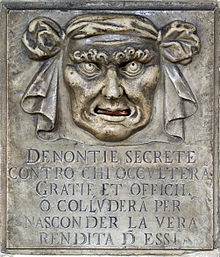

A “Lion’s Mouth” postbox for anonymous denunciations at the Doge’s Palace in Venice, Italy. Text translation: “Secret denunciations against anyone who will conceal favors and services or will collude to hide the true revenue from them.”

In all human societies there are not only individuals who are willing to cooperate, but also those who do not cooperate. People who enrich themselves from a public good without contributing to it themselves are known as free-riders. In behavioural experiments, many people punish such behaviour. However, all modern societies have institutions that take the task of punishing wrongdoers away from the individual. Therefore, people do not directly punish others themselves, they have them punished instead. Establishing an institution to do this job is expensive, and the costs still must be paid even if no crimes are committed. By rights, institutionalised punishment should only be used if many crimes are committed and the benefits therefore exceed the costs.

However, the form of punishment a society chooses depends on how that society deals with second-order free-riders. These are individuals that cooperate but do not punish, thereby cutting the cost of punishment. Because those wishing to punish others, will incur costs and, depending on the circumstances, can even expect them to object. Such second-order free-riders should, therefore, be at an advantage as long as they are not themselves punished.

Without first-order free-riders, second-order free-riders go unnoticed. However, a society with both first and second-order free-riders loses its cooperative equilibrium, as the selfish behaviour of individuals is not punished and they are allowed to succeed within society. “The way we deal with second-order free-riders is key to the establishment of cooperation within society, in order to ensure that the system is not subverted and permanently destabilised,” says Traulsen.

The scientists used a public goods game, a classic model in experimental economics, to study the effect of the two forms of punishment. If second-order free-riders cannot be punished, there are only few players who decide to support institutional punishment. In these cases, punishment is meted out individually. The punishment follows as a reaction to an incident and punishes the wrongdoer quickly and directly. It requires no planning and is inexpensive, as it only costs money if people actually commit a crime. However, if second-order free-riders can be punished, people overwhelmingly opt for punishment by the police – thereby mutually compelling each other to support institutional punishment.

They thus prefer the costlier method, the police, even though it is less efficient. Institutionalised punishment reduces the number of crimes so greatly that the cost-benefit ratio shifts to their detriment: high police taxes to punish a small number of criminals. All the same, few players switch to the less expensive method of direct punishment as they would immediately be punished. “So in our experiment efficiency is traded for stability,” says Milinski. These findings bear out the results of a model of game theory developed in 2010 by Karl Sigmund from the University of Vienna and his co-authors addressing the question of how police-like institutions could come into being.

Contacts and sources:

Dr. Arne Traulsen

Citation: Traulsen, Röhl und Milinski

An economic experiment reveals that humans prefer pool punishment to maintain the commons

Proc. Royal Soc. London B, July 4, 2012, doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0937

Read more at Nano Patents and Innovations

Source: