(Before It's News)

Professor Ann Labounsky, chair of the programs in organ and sacred music at Duquesne University, offers her review of a new volume about Charles Tournemire. Mystic Modern brings together papers from the February 2012 conference on the organ composer (“Gregorian Chant and Modern Composition for the Catholic Liturgy: Charles Tournemire’s L’Orgue Mystique as Guide”), sponsored by CMAA and Nova Southeastern University.

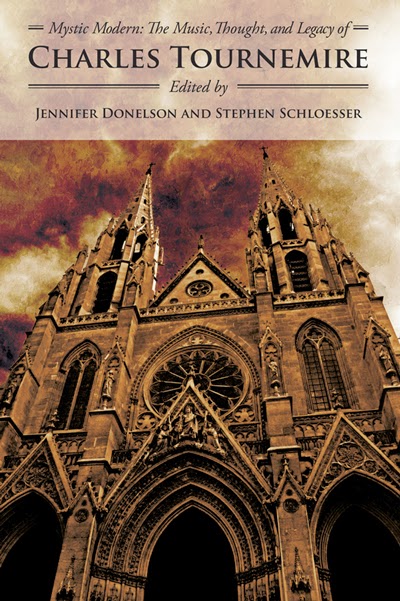

Mystic Modern: The Music, Thought, and Legacy of Charles Tournemire

Charles Tournemire (1877-1939) died in the same year that I was born. I have always found that year fascinating, and in some strange way I felt a special connection to this man. He was certainly a modern composer who influenced Messiaen, Langlais, and many other 20th-century French composers. The extent of his “modernism” led many to dismiss his music as obtuse. His mysticism certainly was another reason for many to dismiss his music as unapproachable.

My first exposure to this modern mystic was during the 1950s in hearing my first organ teacher, Paul Sifler, play some Tournemire on several occasions. I remembered it as a strange, exotic-sounding music, like the Olivier Messiaen music he played, that as a teenager I did not understand. It was later, when I was a pupil of Jean Langlais in Paris during the early 1960s, that I came to know Tournemire’s music in a different way.

Langlais often played Tournemire’s music at Sainte-Clotilde on the organ that Tournemire knew and loved. He often played the Eli, eli, lama Sabacthani from the Seven Words of Tournemire and taught me that movement and the last–Consummatum est–at Sainte-Clotilde on those late Wednesday evenings when the church was dark and we were alone there with those incomparable sounds.

He spoke about Tournemire as someone he knew well–telling me little things about how he taught and how his personality was particularly quirky and unpredictable. He encouraged me to meet Mme. Alice Tournemire in her apartment, the apartment where he lived and taught. She read portions of his journal regarding the Symphonie–Choral, which I was planning to play at Sainte-Clotilde.

The more I played and heard Tournemire’s music, the more fascinated I became with it–for his music is not the type that has instant appeal but rather gets inside your being slowly and compellingly.

Now, through the efforts of Jennifer Donelson and the CMAA board, there is an important academic dimension within this august organization which has sponsored two Tournemire conferences: the first in Miami in 2011 and the second at Duquesne University in 2012. Mystic Modern is the first publication in this outreach that has reproduced the academic papers given at the first Miami conference.

Edited by Jennifer Donelson and Stephen Schloesser, this 456-page book is divided into three sections: Tournemire the Liturgical Commentator, Tournemire the Musical Inventor, and Tournemire the Littéraire. The cover has been carefully chosen to reflect the mystical nature of the book. It is a surrealistic picture of the Basilica of Sainte-Clotilde, with dramatic blood-red clouds in the background. The typeface and illustrations are exquisitely reproduced. Drs. Donelson and Schloesser are to be complimented on the physical beauty of the book, not to mention the depth of scholarship it represents. Whether you are a long-time devotee of Tournemire or someone who is interested in liturgy, music, and theology, this book is a must.

The contents of the bookFive contrasting articles discuss the liturgical aspects of Tournemire’s compositions:

- The Organ as Liturgical Commentator—Some Thoughts, Magisterial and Otherwise, by Monsignor Andrew R. Wadsworth

- Joseph Bonnet as a Catalyst in the Early-Twentieth-Century Gregorian Chant Revival, by Susan Treacy

- Tournemire’s L’Orgue Mystique and its Place in the Legacy of the Organ Mass, by Edward Schaefer

- Liturgy and Gregorian Chant in L’Orgue Mystique of Charles Tournemire, by Robert Sutherland Lord

- The Twentieth-Century Franco-Belgian Art of Improvisation: Marcel Dupré, Charles Tournemire, and Flor Peeters, by Ronald Prowse.

The second section deals with Tournemire’s music and that of his contemporaries in the liturgy:

- Performance Practice for the Organ Music of Charles Tournemire, by Timothy Tikker

- Catalogue of Charles Tournemire’s “Brouillon” [Rough Sketches] for L’Orgue Mystique BNF, Mus., Ms. 19929, by Robert Sutherland Lord

- Creating a Mystical Musical Eschatology: Diatonic and Chromatic Dialectic in Charles Tournemire’s L’Orgue Mystique by Bogusław Raba

- From the “Triomphe de l’Art Modal” to The Embrace of Fire: Charles Tournemire’s Gregorian Chant Legacy, Received and Refracted by Naji Hakim, by Crista Miller

- From Tournemire to Vatican II: Harmonic Symmetry as Twentieth-Century French Catholic Musical Mysticism, 1928–1970, by Vincent E. Rone.

The last section deals with the literary aspects of Tournemire’s music:

- The Composer as Commentator: Music and Text in Tournemire’s Symbolist Method, by Stephen Schloesser

- Messiaen’s L’Ascension: Musical Illumination of Spiritual Texts After the Model of Tournemire’s L’Orgue Mystique, by Elizabeth McLain

- Desperately Seeking Franck: Tournemire and D’Indy as Biographers, by R. J. Stove

- How Does Music Speak of God? A Dialogue of Ideas Between Messiaen, Tournemire, and Hello, by Jennifer Donelson

- Charles Tournemire and the “Bureau of Eschatology” by Peter Bannister.

All of the articles will be of interest, but this review will focus on those of the editors and Dr. Robert Lord.

”How Does Music Speak of God?” by Jennifer Donelson compares in great depth the approaches of the address of God through music in the writings of Tournemire, Messiaen, and the mystic writer from Brittany, Ernest Hello (1828-1885). She explains how the work of Hello, particularly his 1872 composition L’Homme: La Vie–La Science–L’Art, “encapsulates an understanding that was friendly to the Symbolist and anti-positivist tendencies of both composers.”

Tournemire’s influences from Hello are found in his writings, particularly in his unpublished memoirs and correspondence between these two composers. With great care, Donelson explains the differences in philosophy between Messiaen as seeking a perfect expression of the Catholic faith and that of Tournemire. In conclusion, she sums up the answer to the title of her essay in quoting Hello:

In a “clear vision of the role of the Catholic faith in art and culture. Hello saw spiritual realities as more real than material (indeed, as their source) and concluded that, for art to be truly beautiful or ‘sincere,’ the artist must have a clear vision of the world as redeemed by God with the Incarnate Christ at the center of God’s plan for salvation.”

Stephen Schloesser’s chapter is titled “The Composer as Commentator: Music and Text in Tournemire’s Symbolist Method.” Schloesser is well-known for his important book with a somewhat misleading title: Jazz Age Catholicism: Mystic Modernism in Postwar Paris 1919–1933, which may have inspired the title for this CMAA first volume, Mystic Modern.

He shows the importance of the texts in Dom Guéranger’s L’Année liturgique to Tournemire as he composed l’Orgue mystique. So what then is the symbolist method Schloesser describes? He describes it simply as: “. . . an essential relationship between a work and the literary text upon which it is based.”

Robert Lord studied the 1,282 pages of rough sketches of Tournemire’s l’Orgue mystique found in the Bibliothèque Nationale after he had written an extensive article on this seminal work of Tournemire. In his conclusion he stated:

After having completed the manuscript catalogue, we can verify that the “Rough Sketches” document—in sharp contrast to the “Plan” considered in my 1984 study—is far more than a mere framework for L’Orgue mystique. The “Rough Sketches” provide the harmonies, the rhythms, and the paraphrases for forty-two of the fifty-one offices. The BNF Ms. 19929 remains the only evidence we have of Tournemire’s musical preparation for any work he composed.

Dr. Lord’s article “Liturgy and Gregorian Chant” is a reprint of his 1984 article published in The Organ Yearbook, in which he describes Tournemire’s original plan for the composition of l’Orgue mystique and the ways in which Tournemire departed from his plan in the choice of chants. It is fortunate to have these two seminal articles within the same book for easy comparison.

Look for this impressive new volume at the Sacred Music Colloquium in Indianapolis (going on this week through midday July 6). The price is only $40, and if you buy it at the Colloquium, you can save the postage and can get Jennifer Donelson to autograph it for you!

Source:

http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2014/07/a-guest-review-music-of-charles.html