| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Bus Éireann should be let go to the wall. An Post should not.

In this column two weeks ago I argued Bus Éireann should be shut down. Sixteen years of data convinced me the organisation did not deserve the taxpayer’s largesse. Bus Éireann did not pass a simple test: should the state intervene to save it? Competition, not austerity, had sunk its fortunes. Its highly-paid management should be fired, and its staff reassigned or made redundant.

Take the public service obligation routes and school bus businesses into the state proper, or put them out to more than 8,000 privately contracted buses, and let the workers find alternative employment. A harsh call, to be sure, but neither blithe, nor driven by ideology.

Another semi-state faces exactly the same problem this week. The public policy disaster du jour is An Post. The question – should the state intervene – is the same as it was two weeks ago. And here the facts are entirely different.

Not only should An Post see the government reaffirm its commitment to a public mail and financial services network, that commitment should be expanded, and regulations holding An Post back should be removed. Why do I have two different opinions? Well, I examined the facts.

And here they are. There are about 1,100 post offices in Ireland serving roughly 1.7 million customers daily. An Post has closed about 300 post offices in recent years. The company turned a €5.2 million profit last year but €9.6 million of pension costs and other charges, including a 2.5 per cent pay increase for its 11,000 strong staff, put it in the red to the tune of €2.4 million. An Post receives no direct subsidy from the state. Recall that Bus Éireann gets at least two.

An Post has been self-financing since 1986. It received a bailout once, of €12.7 million in 2003. If that sounds like a lot of money, for perspective note that cumulatively, Bus Éireann has received €515 million for the public service obligation routes it runs on behalf of the state from 2000 to 2015, on top of the school bus service it runs for the Department of Education. There were consequences for An Post’s mismanagement as well. When An Post needed its 2003 bailout, its management got the bullet, and en masse. Six of the eight members of the management team went.

An Post is caught in the wave of technological change affecting us all. Its main business is exactly what you think it is – delivering letters – which we write less and less of now. Global snail-mail volumes are down about a quarter since 2004. The company is caught between a decreasing sales volume for its main offering, increased competition, and an increasing wage and capital expenditure bill. Its options are to increase its prices, decrease its cost base, seek government intervention, or diversify its business into other sectors.

Last week, An Post secured agreement from the regulator to increase the price of its stamps from €0.72 to €1, when the European average is about €0.93. A smaller but still significant business is payment processing, which, again, we do less and less of these days within a post office, and more and more on our phones. To survive, An Post needs to change its business model, and to have some of the regulations which shackle its development removed.

To see why, and how, An Post needs to change, and deserves the intervention of the state to help it change, we need to look to the past.

An Post was created in 1984 as a semi-state. Remember what a semi-state is, or at least, is supposed to be: a commercial business which is mostly owned by the Irish government on behalf of the Irish people. Previously An Post was a part of the state proper.

Like all semi-states, An Post’s challenge is to prosper commercially while simultaneously achieving politically determined ends. An Post is mandated by the government to perform a universal service obligation – everyone gets their letters delivered five times a week with next-day delivery as standard. The USO cost An Post around €32 million in 2015.

A series of market liberalisation directives from the European Union in 1999 and 2006 allowed much more competition for postal services. Since 2011, the market has been fully liberalised. An Post’s competitors are not mandated to deliver with the same frequency, nor are they forced to maintain loss-making businesses for political purposes. Remember that companies like Bus Éireann get subsidies from the state for precisely this reason.

Two businesses in one

Unlike Bus Éireann, An Post is not the largest organisation in its product space. A Commission for Communications Regulation study found it accounted for between 30 and 40 per cent of market volume.

It should be said that An Post is really two businesses. The first is the ‘snail-mail’ delivery you’re aware of, or what might be abstracted as a logistics division. It moves things from A to B in a defined space of time with a very high degree of reliability. The second business is a financial services business that processes payments and moves money from A to B in a defined space of time with a very high degree of reliability.

An Post tried to branch out into full banking services in 2010 but the financial health of its putative partner bank collapsed this plan. A number of subsidiary businesses have also been tried – the National Lottery, from 1986 to 2014, the PrintPost service started in 1994, the multi-store voucher business started in 2009, and the PostPoint services it started in 2010. The trend is clear: these people have not been hanging around waiting for the last letter to be posted. They understand and accept they must diversify their business away from mail carrying as soon as possible.

Nor have they been accepting pay increases without productivity increases. I have no problem paying someone more when they are more productive. In fact, I think this process is essential for the economy – people with more incomes buoy demand for goods and services across the system, they pay more tax, and because they are more productive, they become more competitive, which forces their competitors to work harder. Everyone benefits.

A new study by my University of Limerick colleagues Catriona Cahill, Dónal Palcic and Eoin Reeves looked at the productivity of An Post from 1995 to 2014.

Using a range of measures, they found An Post delivered substantial productivity gains up to 2007, and then the recession and indirect competition from other payment and delivery systems caused An Post’s businesses to seize up somewhat. Remember, these productivity gains came as the market was progressively liberalised and competition opened up as well.

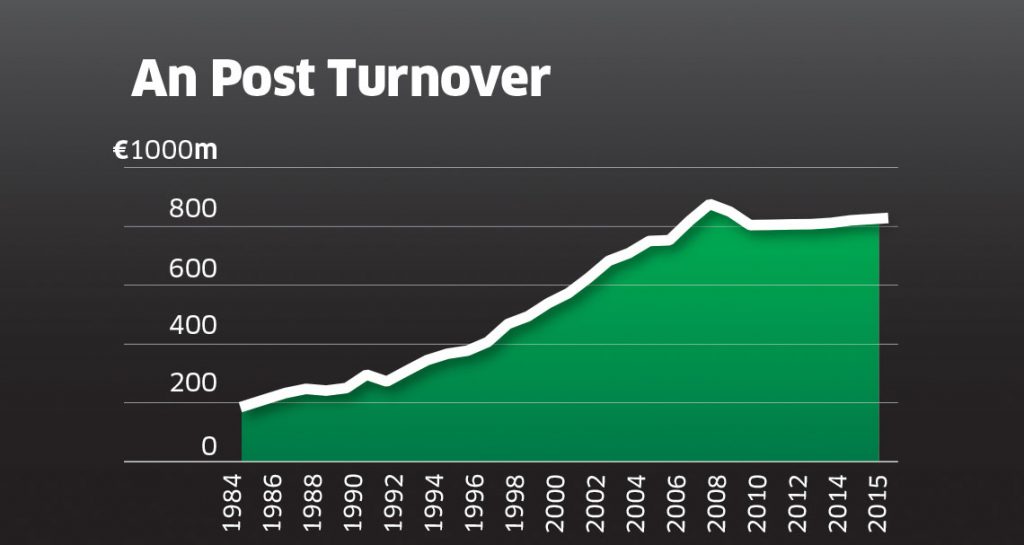

Two measures support the findings of Catriona Cahill and her co-authors. The first is a simple measure of turnover, the amount of money taken in by a business in a year. As you can see from the graph above, turnover grew from about €190 million in 1984 to €875 million in 2007, before falling rapidly throughout the crisis and stabilising at around €826 million in 2015.

Saving An Post

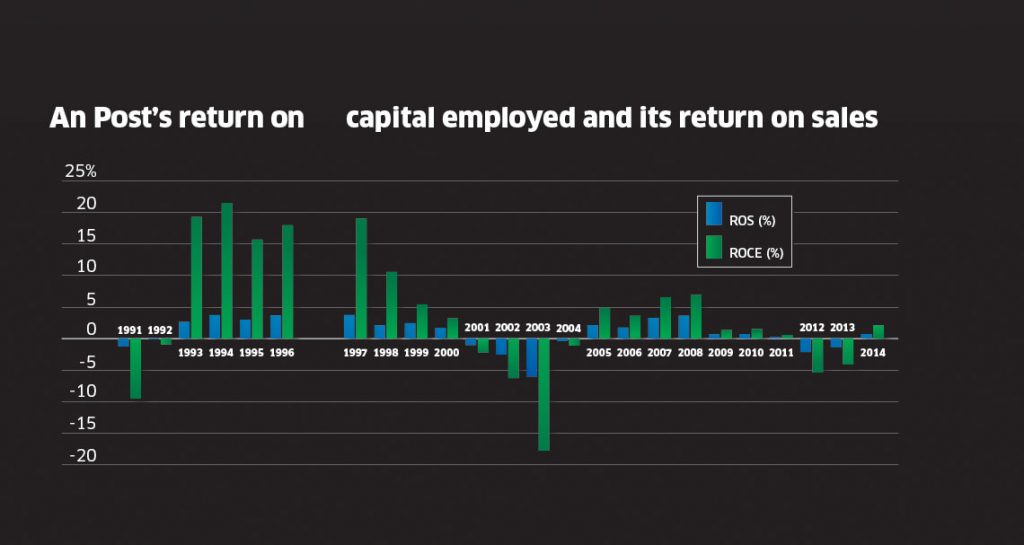

Another two measures are An Post’s return on capital employed and the proportion of profits generated from sales. For both of these measures, positive values are what you want to see. As you can see from the chart, both measures are positive for the 1990 to 2000 period and 2004 to 2011 period, and are negative for the current period, showing the worsening condition of the business in recent times. But it also shows just how strong they have been over the lifetime of their business, even as competition was introduced and technological change really started biting into their revenues. Some 30 years of data show us An Post is not a company that deserves to go to the wall. It meets the test for the intervention of the government on three grounds.

First, it is a genuine anchor of rural development and the 1,100 strong network of post offices is efficient and productive despite the challenges foisted upon it.

Second, the company has historically priced itself lower than average for its services. Before this week’s 38 per cent price increase to €1, Irish stamps were far below the EU average in price at €0.73.

Third, it is obvious the company needs to diversify away from snail mail into other businesses, and because of its large network, An Post will help taxpayers if it does so. The state should support An Post in diversifying because of its demonstrated history of doing exactly this. Its annual accounts show the company has no cash to fund a serious diversification. The state should inject capital to fund these changes for a limited period, as it did before for An Post and has done for other semi-state bodies since then.

The state mandates An Post to deliver mail daily to homes and businesses around the country. This is not sustainable and this regulation should be relaxed to every second day guaranteed. You want next-day delivery? You pay more. This would preserve the public good aspect of An Post’s mission while giving it a fighting chance at commercial viability. Honestly, would you really care if your snail mail came every second day? Would many households even notice?

An Post can succeed both commercially and for the state, but it needs help in the short term to do so, along the lines recommended by the recent report of the post office network business development group. Its 23 recommendations could transform An Post with the state’s help. Otherwise we’ll be back here in a year or two, as falling mail revenues force drastic wage cuts on workers who have demonstrated productivity gains over a long period of time. Those are just the facts, not ideology, and not spin.

Source: http://www.stephenkinsella.net/2017/03/13/bus-eireann-should-be-let-go-to-the-wall-an-post-should-not/