| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

How to price water for conservation in California

Read aguanomics http://www.aguanomics.com/ for the world’s best analysis of the politics and economics of water Yesterday, a California court ruled that tiered water prices (increasing block rates, or IBRs) were “unconstitutional” because the rates were not based on the cost of service at each tier.

This does not surprise me, as tiered rates were originally designed (as I heard from Professor Michael Hanemann, my UC Berkeley advisor and an early consultant for LA’s IBRs) to allow politicians to choose the break between the cheap price for most and higher price for “heavy users.” (The higher price was supposed to be based on the marginal cost of additional water supplies, but that target is often missed, sometimes in brutally unfair ways.)

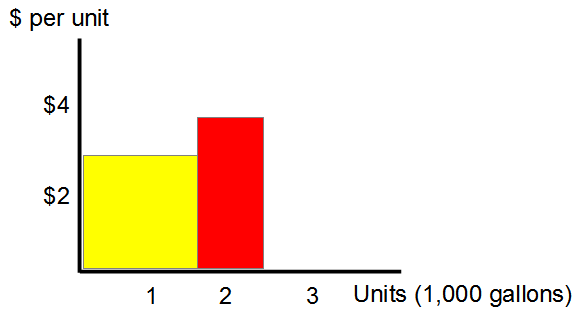

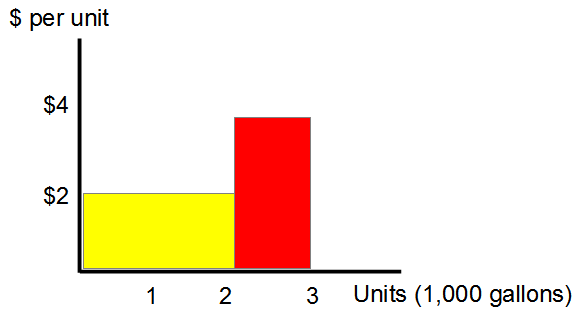

The main idea was that politicians could “move the lever” between blocks and tiers. For example:

|

| Politicians choose the “cut off” between blocks. Red+yellow areas are same in each figure. |

|

| The trouble is that people do not “behave” the same when facing different pricing structures. |

In theory, water managers should not care where the line is, since prices would be set (once politicians chose the break between blocks) to recover their full costs, but that target is very hard to achieve. People do not behave as models predict. That’s why utilities pay $40,000+ to consultants with complex spreadsheets (sample crazy XLSX) who try to make sure that all the customer “buckets” generate the correct revenue.

So that’s why IBRs are so complex to design, destabilize utility finances, do not reflect actual costs, and confuse customers.

It’s for these reasons that I decided to end my support of “some for free, pay for more” water pricing (and all other types of IBRs) a few years ago. IBRs are too complex at the same time as they are ineffective. They are also, of course, unfair when you consider that the number of cheap blocks usually ignores the number of people (i.e., the excuse for “cheap” water).

Instead, I went back to the future, to a single volumetric charge that reflects the cost of water sourcing and delivery and fixed monthly charge that reflects the cost of the water system. Those charges were used for years without many problems before IBRs became trendy in the 1980s.

The only addition I made was of a “scarcity surcharge” that would reflect the cost of getting new water (e.g., desalination).* That charge would be added to the volumetric charge whenever a utility was running out of its “normal” supplies, e.g., California now. This surcharge would apply to ALL water and it would reduce demand in the same way that higher prices reduce demand for any commodity (e.g., coffee, gasoline, etc.).

Let me repeat here the fact that higher prices are also more effective at reducing demand than the very unpopular command and control regulations California has implemented.

* My key innovation was to rebate the resulting excess revenues back to customers. (There are excess revenues because the higher price — based on the cost of new water — is charged against ALL consumption, some of which comes from cheaper sources, e.g., groundwater) The rebates would not be in proportion to consumption (as that would cancel the increase) but per meter. What does that mean? It means that heavy users would end up reducing the service cost of light users who tend to be poorer or more careful with water.

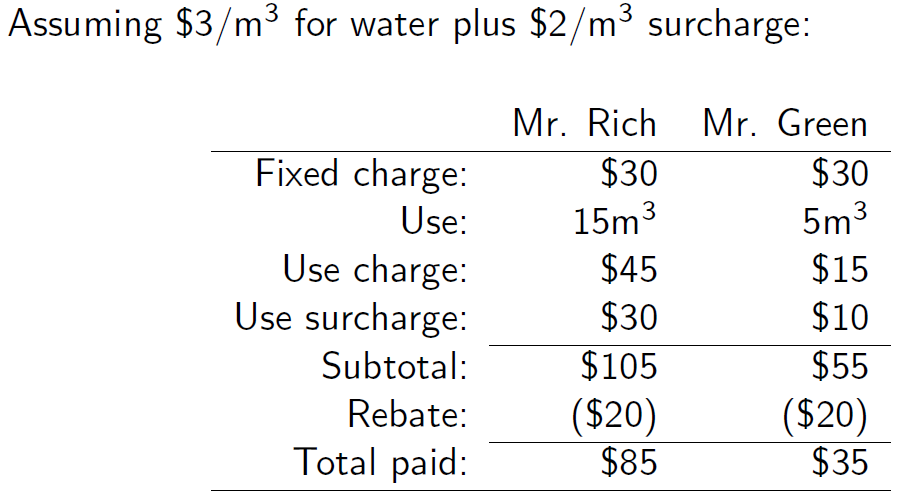

For example (from a presentation I am giving next week in London):

My design, therefore, does not destabilize utility finances and promotes water conservation without hurting the poor. Read more about it here.

Would this design be “constitutional”? I would say yes, in the sense that the utility would not retain any revenue. If that doesn’t work, then I’d recommend that every utility build a small (100,000 gallons/day) desalination plant that costs $10/1,000 gallons to run and use that marginal “cost of service” to set their rates. (San Diego could do this NOW with its 56 MDG plant that will provide water for 7 percent of the population at three times the average cost of water.) If that doesn’t work, I suggest they get smarter lawyers or pack their bags. Californians cannot continue to ignore common sense if they want to avoid drying up and blowing away.

Bottom Line: There are many ways to charge more for water if you need to pay for your water system or protect your limited water supplies. Choose a simple fair way and implement it.

H/Ts to LH, SK, RM and JR

Source: http://www.aguanomics.com/2015/04/how-to-price-water-for-conservation-in.html