| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Bending the cost curve, up

The summary:

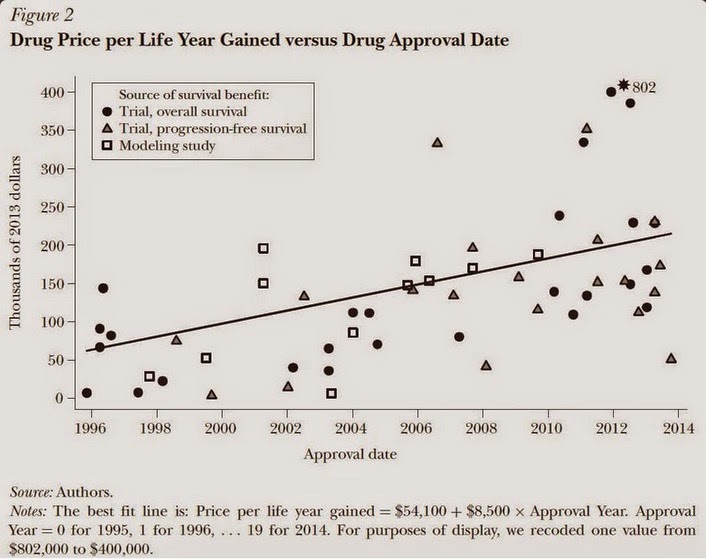

In this paper, we discuss the unique features of the market for anticancer drugs and assess trends in the launch prices for 58 anticancer drugs approved between 1995 and 2013 in the United States. We find that the average launch price of anticancer drugs, adjusted for inflation and health benefits, increased by 10 percent annually—or an average of $8,500 per year—from 1995 to 2013. We argue that the institutional features of the market for anticancer drugs enable manufacturers to set the prices of new products at or slightly above the prices of existing therapies, giving rise to an upward trend in launch prices.

This chart illustrates the phenomenon:

What are the institutional features of the market that make this possible?

Generous third-party coverage that insulates patients from drug prices, the presence of strong financial incentives for physicians and hospitals to use novel products, and the lack of therapeutic substitutes. Under these conditions, manufacturers are able to set the prices of new products at or slightly above the prices of existing therapies, giving rise to an upward trend in launch prices.

The phenomenon is aided and abetted by the Federal government:

By law, Medicare does not directly negotiate with drug manufacturers over prices for prescription drugs covered under the Part B benefit or the oral anticancer drugs covered under Medicare’s pharmacy “Part D” benefit. Section 1861 of the Social Security Act, which requires that the Medicare program cover “reasonable and necessary” medical services, precludes consideration of cost or cost-effectiveness in coverage decisions. Consequently, Medicare covers all newly approved anticancer drugs for indications approved by the FDA.

Meanwhile:

At the time of FDA approval, most drugs are on-patent, and so manufacturers are temporary monopolists.

Elsewhere:

Insurers in states without these requirements and large employers that self-insure have more leeway to determine coverage policies, yet, in the rare instances where third-party payers have tried to place meaningful restrictions on patients’ access to anticancer drugs, they have relented under pressure from clinicians and patient advocacy groups.

–

*The authors are:

David H. Howard, Associate Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, Rollins School of Public Health, and Department of Economics, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Peter B. Bach, Member in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Attending Physician in the Department of Medicine, and Director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City, New York. Ernst R. Berndt, Louis E. Seley Professor in Applied Economics, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Rena M. Conti, Assistant Professor of Health Policy, Departments of Pediatrics and Public Health Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Source: http://runningahospital.blogspot.com/2015/03/bending-cost-curve-up.html