| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Deep-Sea Crabs Grab Grub Using UV Vision

Crabs living half-a-mile down in the ocean, beyond the reach of sunlight, have a sort of color vision combining sensitivity to blue and ultraviolet light. Their detection of shorter wavelengths may give the crabs a way to ensure they grab food, not poison.

“Call it color-coding your food,” said Duke biologist Sönke Johnsen. He explained that the animals might be using their ultraviolet and blue-light sensitivity to “sort out the likely toxic corals they’re sitting on, which glow, or bioluminesce, blue-green and green, from the plankton they eat, which glow blue.”

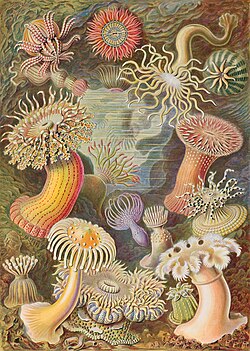

Next the submariners began searching for bioluminescent inhabitants, gently tapping coral, crabs and anything else they could reach with the submersible’s robotic arm to see whether any of the organisms emitted light. The team found that only 20% of the species that they encountered produced bioluminescence (Johnsen et al. 2012). Collecting specimens and returning to the surface, Johnsen and Haddock then photographed the animals’ dim bluish glows – ranging from glowing corals and shrimp that literally vomit light (spewing out the chemicals that generate light where they mix in the surrounding currents) to the first bioluminescent anemone that has been discovered – and carefully measured their spectra.

The discovery explains what some deep-sea animals use their eyes for and how their sensitivity to light shapes their interactions with their environment. “Sometimes these discoveries can also lead to novel and useful innovations years later,” like an X-ray telescope which was based on lobster eyes, said Tamara Frank, a biologist at Nova Southeastern University. She and her collaborators report their findings online Sept. 6 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Frank, who led the study, has previously shown that certain deep-sea creatures can see ultraviolet wavelengths, despite living at lightless depths. Experiments to test deep-sea creatures’ sensitivity to light have only been done on animals that live in the water column at these depths. The new study is one of the first to test how bottom-dwelling animals respond to light.

The scientists studied three ocean-bottom sites near the Bahamas. They took video and images of the regions, recording how crustaceans ate and the wavelengths of light, or color, at which neighboring animals glowed by bioluminescence. The scientists also captured and examined the eyes of eight crustaceans found at the sites and several other sites on earlier cruises.

To capture the crustaceans, the team used the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible. During the dive, crustaceans were gently suctioned into light-tight, temperature-insulated containers. They were brought to the surface, where Frank placed them in holders in her shipboard lab and attached a microelectrode to each of their eyes.

She then flashed different colors and intensities of light at the crustaceans and recorded their eye response with the electrode. From the tests, she discovered that all of the species were extremely sensitive to blue light and two of them were extremely sensitive to both blue and ultraviolet light. The two species sensitive to blue and UV light also used two separate light-sensing channels to make the distinction between the different colors. It’s the separate channels that would allow the animals to have a form of color vision, Johnsen said.

During a sub dive, he used a small, digital camera to capture one of the first true-color images of the bioluminescence of the coral and plankton at the sites. In this “remarkable” image, the coral glows greenish, and the plankton, which is blurred because it’s drifting by as it hits the coral, glows blue, Frank said.

That “one-in-a-million shot” from the sub “looks a little funky,” Johnsen noted. But what it and a video show is crabs placidly sitting on a sea pen, and periodically picking something off and putting it in their mouths. That behavior, plus the data showing the crabs’ sensitivity to blue and UV light, suggests that they have a basic color code for their food. The idea is “still very much in the hypothesis stage, but it’s a good idea,” Johnsen said.

To further test the hypothesis, the scientists need to collect more crabs and test the animals’ sensitivity to even shorter wavelengths of light. That might be possible, but the team will have to use a different sub, since the Johnson-Sea-Link is no longer available.

Another challenge is to know whether the way the crabs are acting in the video is natural. “Our subs, nets and ROVs greatly disturb the animals, and we’re likely mostly getting video footage of stark terror,” Johnsen said. “So we’re stuck with what I call forensic biology. We collect information about the animals and the environment and then try to piece together the most likely story of what happened.”

Here, the story looks like the crabs are color-coding their food, he said.

Devising a strategy for collecting crustaceans ranging from crabs to isopods under dim red light – to protect their sensitive vision – by luring or gently sucking them into light-tight boxes, the submersible’s crew then sealed the animals in boxes to protect their vision from harsh daylight when they reached the surface. Back on the RV Seward Johnson, Frank painstakingly measured the weak electrical signals produced by the animals’ eyes in response to dim flashes of light ranging from 370nm to over 600nm and found that the majority of the creatures were most sensitive to blue/green wavelengths, ranging from 470nm to 497nm (Frank at al. 2012).

Most surprisingly, two of the animals were capable of detecting UV wavelengths. Even though there is no UV left from the sun at this depth, Johnsen explains, ‘Colour vision works by having two channels with different spectral sensitivities, and our best ability to discriminate colours is when you have light of wavelengths between the peak sensitivities of the two pigments.’ He suspects that combining the inputs from the blue and UV photoreceptors allows the crustaceans to pick out fine gradations in the blue-green spectrum that are beyond our perception, suggesting, ‘These animals might be colour-coding their food’: they may discard unpleasant-tasting green bioluminescent coral in favour of nutritious blue bioluminescent plankton.

Finally, after recording the crustacean’s spectral sensitivity, Frank – from Nova Southeastern University, USA – measured how much light the animals’ eyes had to collect before sending a signal to the brain (the flicker rate). She explains that there is a trade-off between the length of time that the eye collects light and the ability to track moving prey. Eyes that are sensitive to dim conditions lower the flicker rate to gather light for longer before sending the signal to the brain. However, objects moving faster than the flicker rate become blurred and their direction of motion may not be clear.

The crustaceans’ flicker rates ranged from 10 to 24Hz (human vision, which is sensitive to bright light, has a flicker rate of 60Hz) and the team were amazed to find that one crustacean, the isopod Booralana tricarinata, had the slowest flicker rate ever recorded: 4Hz. According to Frank, the isopod would have problems tracking even the slowest-moving prey. She suggests that as it is a scavenger, it is possible that it may be searching for pockets of glowing bacteria on rotting food and it might achieve the sensitivity required to see this dim bioluminescence with extremely slow vision.

Having shown that bioluminescent benthic species are scarce but the phenomenon itself is not, Johnsen is keen to return to the ocean floor to discover more about the exotic creatures that reside there. ‘We would love to go back, get more basic data. We’ve only scratched the surface’, he says, adding, ‘When you are down there you are cramped and cold and stiff, but at the end of a dive I never want to come back up.’

Contacts and sources:

Karl Bates

Duke University

Kathryn Knight

The Company of Biologists

Citations: Light and vision in the deep-sea benthos I: Vision in Deep-sea Crustaceans. Frank, T., Johnsen, S. and Cronin, T. (2012). Journal of Experimental Biology. DOI: 10.1242/jeb.072033

Light and vision in the deep-sea benthos II: Bioluminescence at 500-1000 m depth in the Bahamian Islands. Johnsen, S., et. al. (2012). Journal of Experimental Biology. DOI: 10.1242/jeb.072009

2012-09-06 02:13:53

Source: http://nanopatentsandinnovations.blogspot.com/2012/09/deep-sea-crabs-grab-grub-using-uv-vision.html

Source: