| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

What’s In A Name?: Scientific Name Use For Anoles, By The Numbers

As should be evident from several recent Anole Annals posts and comments, Nicholson and colleagues published a paper last week proposing that “It is time for a new classification of anoles.” Among a number of arguments in favor of splitting up the genus Anolis, Nicholson et al. (2012) argue that use of a single genus name hinders scientific communication about these animals. This argument has generated a lot of discussion (e.g., a post by Sanger, and two different threads of comments found here and here), and I thought it might be useful to continue the discussion with a bit of information about the usage of anole names in the scientific literature.

In a comment on an earlier post, Duellman argued that a genus name does not simply exist to reflect systematic knowledge – it’s a (hopefully stable) handle that conveys information about identity to a very wide audience, from laypersons to college students to ecologists, conservationists, and systematists. My impression has always been that this is especially true for Anolis – more so that for many other groups of organisms. For example, geckos are commonly known, even to scientists, by their common name “gecko,” and we find this term in paper titles and abstracts. I don’t think this is true for anoles – it seems to me that we more often simply call them “Anolis“.

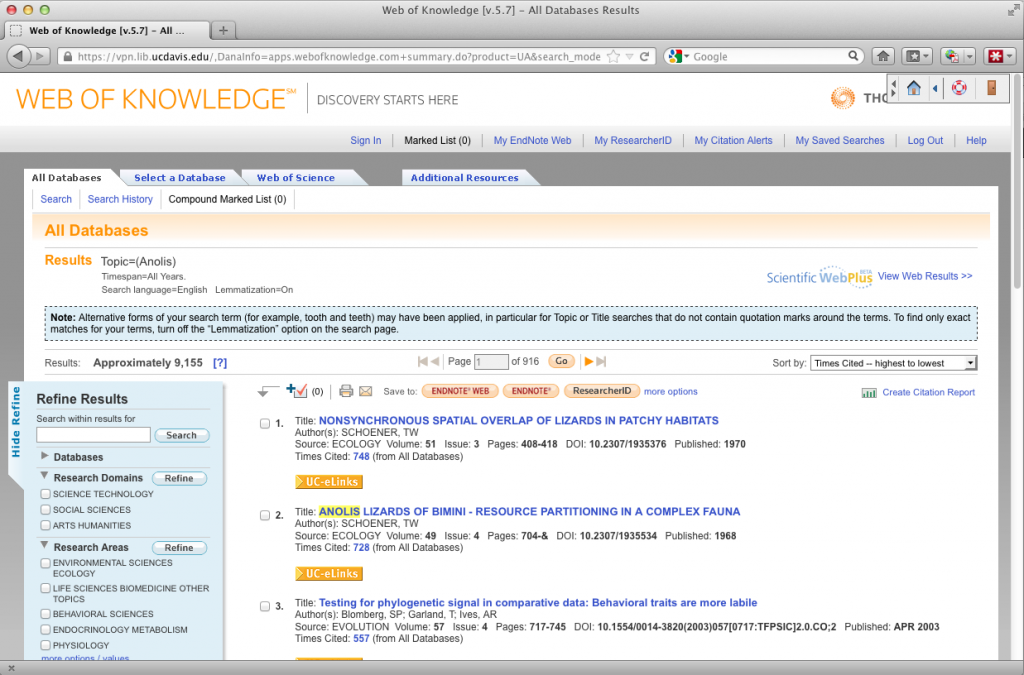

To see if this is actually the case, I decided to pull some numbers from Web of Knowledge. I conducted a series of “Topic” searches for various taxonomic names, such as “Anole”, “Anolis“, “Gecko”, etc., and recorded the numbers of matching records for each search. Records include instances in which a term is found in the title, keywords, or abstract of any book or article recorded in the Web of Knowledge academic database. The numbers returned are reflective of my university’s library holdings (University of California), and will be different if conducted elsewhere; I also didn’t spend any time processing the results, but I don’t think that should qualitatively affect any results.

Here’s what I found for anoles vs. geckos:

Anole 844

Anolis 9,155

Dactyloidae 3

Polychrotidae 200

Gecko 8,877

Gekko 1,199

Gekkonidae 1,516

Here are the eight genera proposed by Nicholson et al. (2012). All of the non-Anolis names have a previous history of use, but they’re relatively minor compared to Anolis. Obviously, we don’t expect them to compare to Anolis, but I did want to give some numbers on their present “searchability”:

Anolis 9,155

Audantia 0

Chamaelinorops 22

Ctenonotus 6

Dactyloa 12

Deiroptyx 3

Norops 146

Xiphosurus 2

Finally, here are numbers for some more inclusive groups. I find it remarkable that “Anolis” returns more records than “Squamata”! We can eventually beat “Anolis” if we continue to widen the circle though, and I’ve included some examples:

Iguanidae 1,209

Iguania 299

Squamata 8,409

Squamate 1,135

Lizard 64,591

Reptilia 249,702

Reptile 250,569

In addition to showing that the Anolis literature is extraordinarily rich, I think the numbers bear out the common intuition that the genus name “Anolis” is the de facto name for this group of lizards within the scientific community. If your undergraduates would like to learn about anole community ecology for their upcoming term paper, they’d be much better off searching for “Anolis community ecology” (135 hits) than “anole community ecology” (23 hits). Furthermore, there’s overlap in the use of these terms, with “Anole” being largely nested within “Anolis“: 79% of the “Anole” results also come up in a search for “Anolis” – you can ignore the term completely, and still recover nearly 80% of the records that use it. Conversely, only 7% of “Anolis” results come up if you search for just “Anole”. The opposite general pattern exists for geckos. For that group, Linnean names are less widely used than the common name “Gecko” to communicate to other scientists. One might argue that this isn’t a fair comparison, since we’ve always had different names for various gecko lineages, but I think this is beside the point, which is that “Anolis” is an incredibly communicative and scientifically useful handle, and that we can’t simply replace it by using a common name or higher taxonomic name when we wish to refer to the entire group in the future. If we’re to adopt the Nicholson et al. classification for anoles, should we put “Anolis” in the keywords of all future papers on Deiroptyx or Xiphosurus, so that the group continues to have a useful, searchable name? Alternatively, should we make efforts to ensure that newcomers learn the taxonomic histories of these other genera, so that they can carry out their research effectively? My hunch is that neither approach would work well – historical taxonomic details quickly become arcane, and I think it would be too much to ask for non-specialists to remain aware of these.

Anoles have become a model system in biology, and for whatever reason – historical, idiosyncratic, legitimate, or perverse – the name “Anolis” is what we use for them, and the name has come to serve the community well. Several other model systems are also known primarily by genus names, in some cases despite being old and diverse lineages, as Thom Sanger very recently discussed. Although we all know what “fruit flies” are, we tend to refer to them as “Drosophila,” and because of the history of use of that name, there would be many costs to significantly redefining it (see the references linked near the bottom of Thom’s post for a very interesting discussion of debated proposals to split up Drosophila). For what it’s worth, the genus and common names for Anolis and Drosophila return similar ratios of records on Web of Knowledge: “Drosophila” yields 331,074 results, while “fruit fly” returns 33,532. Just as in anoles, the genus name returns roughly ten times more results than the common name. As Thom mentioned, the genus name “Drosophila” has been maintained by that community despite proposals to carve it up. Given the similarities of these groups (both are model organisms studied by huge communities, and both are primarily referred to by a genus name), it’s worth considering why that community decided to maintain a more inclusive name.

I think that for anoles, there’s much to lose by abandoning the primary name used for this group for the past century. I’m skeptical of the proposal that “the single genus concept can be a hindrance to scientific communication regarding evolutionary events and directions of future research” (Nicholson et al. 2012, p. 13). The numbers show that the name “Anolis” has been the handle of choice for communicating all sorts of findings about anoles for many decades, and scientific communication about anoles has been, if anything, exceptional during this period. If progress resolving the phylogenetic relationships of anoles seems late in coming (and I would argue that we still have a ways to go), I think it’s because it’s a legitimately difficult problem rather than because we don’t recognize enough lineages within the current Linnean taxonomy. I’d certainly be interested in seeing any data that might support Nicholson et al.’s criticism of the single genus concept, but even if that argument can be buttressed empirically, I think we need to carefully weigh the impact of dramatically redefining a genus name like “Anolis” before adopting a radically different taxonomy.

KIRSTEN E. NICHOLSON, BRIAN I. CROTHER, CRAIG GUYER & JAY M. SAVAGE (2012). It is time for a new classification of anoles (Squamata: Dactyloidae) Zootaxa, 3477, 1-108

2012-09-19 21:03:46

Source: http://www.anoleannals.org/2012/09/19/whats-in-a-name-scientific-name-use-for-anoles-by-the-numbers/

Source: