| Visitors Now: | |

| Total Visits: | |

| Total Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Strange Martian Structures In Ice-coated Beauty Of Silver Island: Second Largest Structure On Mars

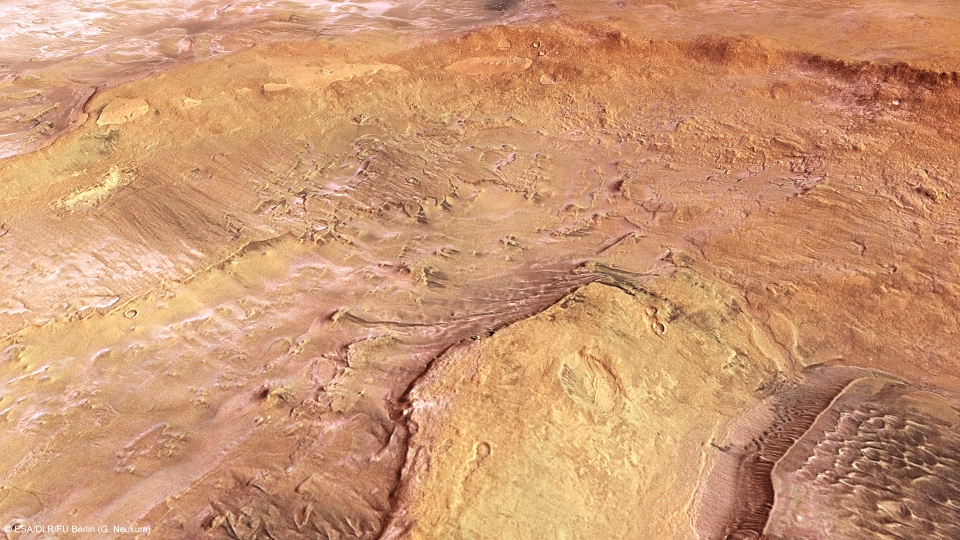

Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum) Download full size:

On 8 June, the high-resolution stereo camera on Mars Express captured a region within the 1800 km-wide and 5 km-deep Argyre basin, which was created by a gigantic impact in the planet’s early history.

After Hellas, the Argyre impact basin is the second largest on the Red Planet.

Argyre and Hooke Crater perspective view: This computer-generated perspective view was created using data obtained from the High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) on ESA’s Mars Express. Centred at around 45°S and 314°E, this image has a ground resolution of about 22 m per pixel. The lower right of the image shows the wind-formed dunes within Hooke Crater, while small deposits of frozen carbon dioxide ice lie within the crater, the top left of the image starts to show the more extensive ice lying on the surrounding Argyre Planitia.

Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum) Download full size ![]() HI-RES JPEG (Size: 564 kb)

HI-RES JPEG (Size: 564 kb)![]() HI-RES TIFF (Size: 15 690 kb)

HI-RES TIFF (Size: 15 690 kb)

The name stems from the Greek word ‘argyros’ (silver) and Argyre was an ‘island of silver’ in Greek and Roman mythology. Giovanni Schiaparelli, the famed Italian astronomer, gave the name to this bright region on Mars in his detailed 1877 map.

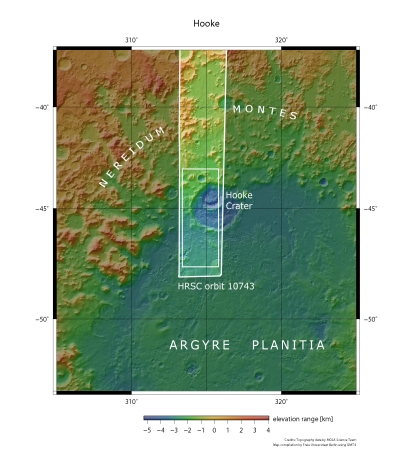

At the centre of the larger impact basin is a flat region known as Argyre Planitia. The Mars Express images in this release all show a portion of the northern part of this plain, with a large portion of each image dominated by the western half of the 138 km-wide Hooke Crater, named after the British physicist and astronomer Robert Hooke.

Hooke Crater and the surrounding Argyre Planitia are seen in broader context. The smaller rectangle shows the region covered in this ESA Mars Express HRSC image release.

Credits: NASA MGS MOLA Science Team Download full size ![]() HI-RES JPEG (Size: 178 kb)

HI-RES JPEG (Size: 178 kb)![]() HI-RES TIFF (Size: 3717 kb)

HI-RES TIFF (Size: 3717 kb)

Most of Argyre Planitia has been shaped by wind, glacial and lacustrine (lake-based) processes, creating the smoother appearance of the landscape surrounding Hooke Crater.

Inside Hooke Crater itself, prevailing wind activity has formed dunes and helped to create linear erosion features, clearly seen in the following topographic image.

Argyre and Hooke Crater in context: This colour-coded plan view is based on a digital terrain model of the region, from which the topography of the landscape can be derived. The colour coding highlights the difference between the elevation of the hills to the right of the image and the depth of the Argyre Planitia region as well as Hooke Crater itself. This topographic map also increases the visibility and contrast of the dune features within Hooke Crater. Centred at around 45°S and 314°E, the image has a ground resolution of about 22 m per pixel.  Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum) Download full size HI-RES JPEG (Size: 2145 kb)

Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum) Download full size HI-RES JPEG (Size: 2145 kb)![]() HI-RES TIFF (Size: 22 058 kb)

HI-RES TIFF (Size: 22 058 kb)

The most striking feature of this image release, shown clearly in the first image at the top of the page, is the icing sugar-like covering of the surface to the south (left) of the image. This is frost, but made of carbon dioxide, not water.

Carbon dioxide ice is commonly seen on the surface of Mars, and has long been thought to form only at ground level, freezing out of the atmosphere as frost, which is most likely the case here.

3D anaglyph view Hooke Crater: Argyre Planitia And Hooke Crater Imaged During Revolution 10743 On 8 June 2012 By ESA’s Mars Express Using The High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC). Data From HRSC’s Nadir Channel And One Stereo Channel Are Combined To Produce This Anaglyph 3D Image That Can Be Viewed Using Stereoscopic Glasses With Red–Green Or Red–Blue Filters. Centred At Around 45°S And 314°E, The Image Has A Ground Resolution Of About 22 M Per Pixel.

Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum) Download full size HI-RES JPEG (Size: 2187 kb)![]() HI-RES TIFF (Size: 17 817 kb)

HI-RES TIFF (Size: 17 817 kb)

The lowlands to the south (left in the first image) of Hooke and regions within the crater are covered by a thin ice layer. However, it is lacking on the inner north-facing crater wall. It was probably melted there by the Sun, as indicated by the timing of the image.

Taken at around 4:30 in the local afternoon and during the southern hemisphere’s mid-winter, the Sun would have been just over 20 degrees above the horizon. It should then have been able to melt ice on the steeper north-facing slopes, but would probably not have had enough time to warm and melt any on low-lying horizontal surfaces.

Schiaparelli would doubtless have marveled at the exquisite images coming back from Mars Express, which continues to provide today’s scientists with a bounty of wonderful data.

The Mars Express VMC team here at ESOC are delighted to publish today’s special treat: a movie carefully compiled from 600 VMC images snapped during a single, complete 7-hour orbit on 27 May 2010. This video shows what future astronauts would likely see from their cockpit window: Mars turning below them as they sweep in orbit around the Red Planet, our beautiful planetary neighbor!