| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

Never Seen Before Chaos in Cosmos

A solar system is formed by a large cloud of gas and dust. The cloud of gas and dust condenses and eventually becomes so compact that it collapses into a ball of gas in the centre. Here the pressure heats up the matter and creates a glowing ball of gas, a star. The remainder of the gas and dust cloud rotates as a disc around the newly formed star. In this rotating disc of gas and dust, the material begins to accumulate and form larger and larger clumps, which finally become planets.

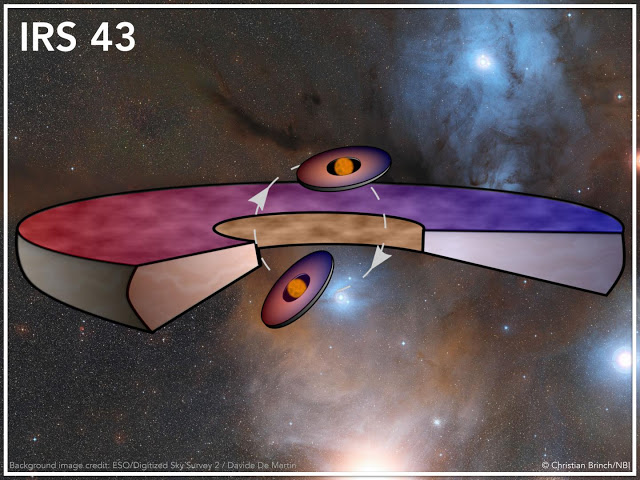

But now the researchers have observed something highly unusual: a binary star with not just two, but three rotating gas discs.

“The two newly formed stars are both the size of our sun and they each have a rotating disc of gas and dust similar to the size of our solar system. In addition, they have a shared disc that is much larger and crosses over the other two discs. All three discs are staggered and this breaks with everything we have seen so far,” says Christian Brinch, assistant professor in the research group Astrophysics and Planetary Science and the Niels Bohr International Academy at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen.

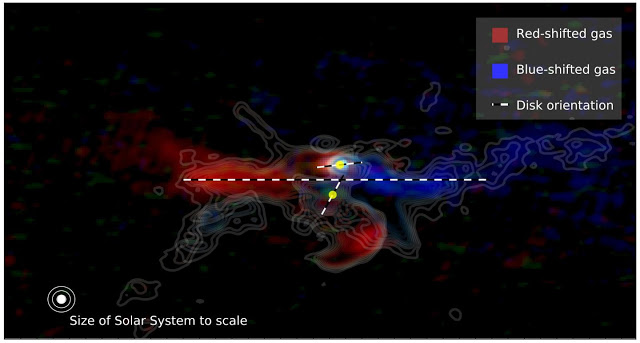

“What we can observe is the gas itself, because the molecules are excited by the heat from the stars and therefore emit light in the infrared and microwave range. By studying the wavelength of the light you can see whether the light source is moving farther away or is getting closer. If the light shifts towards red wavelengths it is moving farther away, while blue shift light is moving closer and thus we can see that the three planet-forming discs are almost ‘tumbling around’ and are skewed relative to each other,” explains Christian Brinch.

The researchers do not know why it is not a ‘nice’ system where the rotating discs of gas lie flat in relation to each other. Perhaps the formation occurred in a particularly turbulent manner.

“We will use computer simulations to try to understand the physics of the formation process. Perhaps it is a dynamic process of formation, which happens often and then it corrects itself later on. We will try to clarify this. We will also apply for more observation time on the ALMA telescope to study the planet-forming discs in even higher resolution to get more detailed information about their chemical composition,” says Jes Jørgensen, associate professor in the research group Astrophysics and Planetary Science at the Niels Bohr Institute and Centre for Star and Planet Formation, University of Copenhagen.

Contacts and sources:

Jes Jørgensen, Associate professor in the research group Astrophysics and Planetary Science at the Niels Bohr Institute and Centre for Star and Planet Formation, University of Copenhagen.

Source: