| Online: | |

| Visits: | |

| Stories: |

| Story Views | |

| Now: | |

| Last Hour: | |

| Last 24 Hours: | |

| Total: | |

The Places of “Evangelical Gotham”

Today we continue our roundtable review of Kyle Roberts' Evangelical Gotham with a post from longtime RiAH blogger Lincoln Mullen. You can see the rest of the posts in this series here.

|

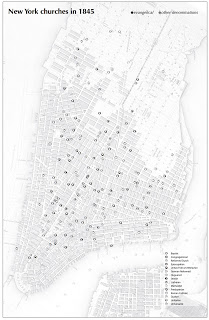

| New York's churches 1845 from Roberts, Evangelical Gotham |

In his elegantly written account, Kyle Roberts takes his readers on a tour of Evangelical Gotham. The book has a strong chronological through line, explaining how evangelicals went through three distinct periods in bringing their message of conversion and reform to New York City (10–11). While the spatial organization of the book is less obvious from its table of contents, Evangelical Gotham is a book that is fundamentally organized around place. This may seem like an obvious point to make about a book that focuses on a single city, but my aim is to show how Roberts uses spatial concepts.

Evangelical Gotham is explicit in its debt to the concept of “crossing and dwelling” articulated by Thomas Tweed. Roberts makes this clear in his first chapter, where he writes about spiritual autobiographies at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. He takes a fresh approach to this topic by giving conversion narratives a meaning both in geographic and spiritual space. Evangelicals crossed religious boundaries by converting, but many of them did so at the same time that they were crossing the ocean or moving to the city. And once they arrived in New York, these newly converted evangelicals had to dwell not just in the city but also had to find a church or “community of faith” (27).

Geographic and spiritual space were thus experienced in mutually constitutive ways. This conjunction becomes a key to understanding much of the book, as does the emphasis on conversion. Conversion and other themes such as benevolence or reform recur throughout the book because they were perennial evangelical concerns. A real contribution of the book is the way that Roberts sets those concerns in relation to other questions such as denominational affiliation and worship practice. A key sentence comes in the conclusion, where he writes, “As denominational and sectarian choices proliferated, evangelicalism's appeal lay in the ease with which its small core of common principles could be incorporated into the matrix of beliefs and practices provided by them” (254). As any number of studies have told us, evangelicalism is a transdenominational movement focusing on conversion. Evangelical Gotham shows how people who held those evangelical convictions had to live them out in different churches competing within a single city. If most studies of evangelicalism are weighted towards crossing, then this book gives due emphasis to dwelling.

This book can also be understood in terms of the meaning of places. Geographers make a distinction between space and place. Space is abstract location: the island of Manhattan, or the latitude and longitude coordinates that identify it. Place is the meaning that humans make out of space. This book shows how evangelicals made, or attempted to make, the space of New York into a religiously meaningful place. As he points out, for evangelicals “sacredness was understood to come not from the physical space itself,” as it might for Catholics or Episcopalians who consecrated worship spaces, “but from the actions of believers who gathered there to hear the gospel preached” (8).

Other scholars have used that same concept, but Evangelical Gotham applies it a great many kinds of places. Turning different kinds of spaces into places that had meaning for evangelicals is thus a kind of analysis common to each chapter. Doubtless I have left out some of these kinds of places or movements, but a non-exhaustive list includes immigration into and out of the city; the locations of churches within the city and their movement over time; the domestic space of the home; the architecture of churches and the use of storefronts and homes as worship spaces; “mixed use” spaces put to both religious and commercial uses, not least the homes of benevolent organizations like the American Tract Society and American Bible Society; “bethel” services held on board ships; the commercial space of both the religious marketplace and the financial and consumer marketplaces; the grid of New York streets that controlled the placement of new churches and the expansion of evangelicalism; riots in the streets targeting abolitionist evangelicals; and networks of commerce and mission, expressed not least in networks of print.

The discussions in the book are under-girded by Roberts's maps, in which he plots the locations of churches over time and categorizes them by denomination and whether or not they were evangelical, and by his appendix, in which he gives membership figures for various denominations over time. This empirical work lets him claim that “evangelical congregations emerged from the margins to the center of the urban spiritual marketplace,” eventually constituting 59 percent of churches (264). And it lets him claim that “the percentage of New Yorkers who had a conversion experience and joined an evangelical church increased steadily from 4 percent of the city's adult population in 1790 to 15 percent in 1855.” These figures are also put to good use in showing whether congregations attracted new members via converting the lost or merely attracting existing evangelicals (173). This quantitative work is pursued with a rigor seldom seen since the work of Terry Bilhartz or Paul Johnson,

I do not wish to give the impression that the book is as laden down with theory as this review, because it isn't. And for that matter, the book touches on a great many topics, from abolition to the financing of churches, which I do not have space to discuss here. This book is likely to become essential reading for anyone wishing to understand early nineteenth-century evangelicalism or how religion functions in urban spaces. It seems to me that all of the contributions in the book are aligned to these questions about crossing and dwelling, space and place—just as evangelical churches and organizations were once aligned to the grid of New York streets.

A Group Blog on American Religious History and Culture

Source: http://usreligion.blogspot.com/2017/03/the-places-of-evangelical-gotham.html